In the summer of 1966, in Paterson, New Jersey, a triple homicide at a local restaurant would ignite a firestorm of controversy, ultimately leading to a groundswell of pop-culture support, allegations of wrongful conviction, and a big-budget Hollywood film.

It was about two-thirty a.m. on the morning of June 17th, 1966. Fifty-one-year-old James Oliver, part owner and bartender at the Lafayette Grill on East 18th Street in Paterson, New Jersey, was busily counting out the day’s receipts at the cash register behind the bar. The establishment had not yet closed, and a few patrons were still seated around the restaurant, finishing their drinks and getting ready to call it a night.

Suddenly, the door burst open, and two black men strode into the bar. One of them was brandishing a .32 caliber pistol, the other a double-barreled shotgun. James Oliver just had time enough to sling an empty beer bottle at the intruders—which unfortunately missed its mark—before the gunmen opened fire.

James Oliver was hit in the back by a shotgun blast as he attempted to flee from behind the bar. Sixty-year-old Fred Nauyoks, who had been seated at the bar, was shot in the head with the pistol. Forty-two-year-old patron William Marins was also shot with the pistol, in the temple just above his eye.

As the shooters turned to leave the establishment, they spotted fifty-one-year-old Hazel Tannis, who had been sitting at a table behind the open door of the bar and had initially been out of the assailants’ line of sight. The gunmen bore down on her as she screamed for help, shooting her once with the shotgun and four times with the pistol. They then exited the restaurant and headed back to their vehicle, which was double parked around the corner.

First on the scene was petty criminal Alfred Bello, who had heard the gunshots and saw the two men leaving the Lafayette Grill, at which point he hid in an alley until the shooters had driven away. Bello subsequently entered the restaurant, surveyed the carnage, and then stole over sixty dollars from the open cash register, which he took to a friend of his down the street. To Bello’s credit, he did return to the Lafayette thereafter and report the murders to police.

Both James Oliver and Fred Nauyoks were pronounced dead at the scene. Hazel Tannis was still alive, though she had multiple gunshot wounds through her neck, arm, lung, intestines, spleen, and stomach. She would succumb to her injuries nearly a month later. The fourth victim, William Marins, survived the attack, though he would ultimately lose his sight in one eye.

Since the gunmen had not robbed the Lafayette Grill, investigators presumed that the onslaught was an act of revenge for an incident in the city earlier that evening, whereby a white man had killed a black tavern owner following an argument. The area of Paterson where the Lafayette was situated, it should be noted, was a predominantly white neighborhood.

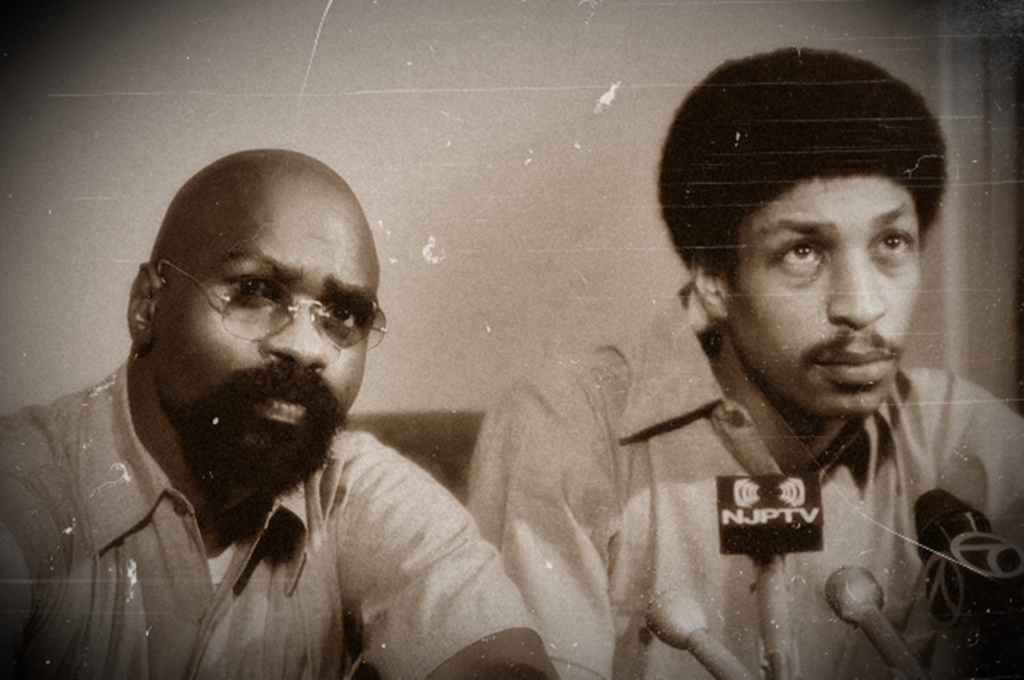

Less than fifteen minutes after the shooting, Sergeant Theodore Capter pulled over a white 1966 Dodge Polara which sped past his patrol car in the opposite direction. This vehicle was driven by a man named John Artis, and his passenger was the well-known middleweight boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. However, since Sergeant Capter was under the mistaken impression that he was looking for a car containing three black men, not two, he let Artis and Carter go on their way.

When Sergeant Capter arrived at the Lafayette, though, he was set straight about the car’s and the assailants’ descriptions. According to Alfred Bello and another eyewitness named Patricia Valentine who lived above the bar, the two black male shooters had driven away from the scene in a white vehicle with taillights in the general shape of a butterfly. Bello also said that the car had out-of-state license plates with orange or gold letters on a blue background.

Capter then realized that the car he had pulled over earlier had New York plates—which had gold lettering on a dark blue background—and also had distinctive, butterfly-shaped taillights. He and another officer headed off in pursuit, and quickly tracked down the Dodge Polara again, after which they returned to the Lafayette with Artis, Carter, and the vehicle.

Patricia Valentine stated that this was the same car she had seen driving away from the restaurant after the shooting, and a detective who searched the vehicle at the scene later testified that he had found a 12-gauge shotgun shell in the trunk, as well as a .32 caliber pistol round under the front passenger seat. The actual weapons used in the multiple murder have never been found.

John Artis and Rubin Carter were taken into custody and interrogated for 17 hours, but released after surviving victim William Marins and other eyewitnesses failed to identify them as the shooters. There was, further, no forensic evidence linking either man to the attack, and both passed a lie detector test.

Over the ensuing months, however, the case would grow ever more convoluted, and a great deal of dissention still exists over whether Artis and Carter were the true culprits or not. Alfred Bello and his criminal colleague, Arthur Bradley, later told police that they believed Artis and Carter were the men they had seen emerging from the Lafayette Grill, and based on this testimony, both men were eventually arrested and indicted for the murders.

At the trial, Rubin Carter and John Artis claimed they had been at a club called the Nite Spot at the time of the slayings, and their defense attorney produced several witnesses who claimed they had seen them there until around three a.m. The defense also argued that the bullet found in the Dodge Polara had a brass casing, unlike the copper casing on the spent cartridge found in the bar.

Despite the defense’s efforts, Artis and Carter were convicted in 1967 by an all-white jury, receiving three life sentences each. But in 1974, Alfred Bello and Arthur Bradley recanted their statements, saying that it had not been Artis and Carter that they had seen on the night of the shooting after all. The motion to convene a new trial, though, was unsuccessful.

During the media coverage of the investigation, several high-profile celebrities began agitating on Rubin Carter’s behalf, including Muhammad Ali, and Bob Dylan, who wrote the song “Hurricane” in Carter’s honor. At issue was not only the fact that various promises had allegedly been made to Alfred Bello in exchange for his testimony against Carter (for example, he hoped to receive the substantial reward on offer for helping to capture the killers), but also that there might have been some degree of racism on the part of witnesses, and responding officers, who some sources claimed had planted evidence in Carter’s car.

A second trial took place in 1976, at which Bello again identified Artis and Carter as the two men he had seen leaving the Lafayette after the shooting. The defense countered by presenting the original testimony of surviving victim William Marins, who had described the shooters as looking completely different than Artis and Carter, and pointed out inconsistencies in the testimony of witness Patricia Valentine. The prosecution won the day once again, though, and Artis and Carter’s convictions were upheld.

John Artis was eventually paroled in 1981, and following numerous appeals, Rubin Carter was released from prison on a writ of habeas corpus in 1985, with the judge going on the record as stating that he felt the original convictions of both men had been based on “racism rather than reason,” and should therefore be overturned. The prosecution considered trying the men a third time, but ultimately decided to dismiss the initial indictments. The triple murder at the Lafayette Grill, therefore, officially stands as unsolved.

Interestingly, in 1996, Carter was again arrested, this time in Toronto, after police mistakenly identified him as a thirty-odd-year-old suspect who had allegedly sold drugs to an undercover officer. Carter was nearly sixty at the time.

Not everyone believes that Rubin Carter and John Artis were innocent of the homicides, however, pointing out that Carter in particular had an extensive criminal history of muggings and assault stemming back to a non-fatal stabbing he had perpetrated when he was only eleven years old. Carter’s critics also highlight the fact that he was discharged from the Army in 1956 after being court-martialed four times.

Not only that, but a bail bondswoman named Carolyn Kelley, who had helped Carter raise funds for a second trial, alleged that he had beaten her unconscious in 1976 during a dispute over a hotel bill, though there was insufficient evidence to prosecute Carter on these charges, which he denied.

Additionally, those who are convinced of Carter’s guilt often call attention to the fact that multiple witnesses on the night of the shooting described a vehicle nearly identical to that owned by Rubin Carter, and argue further that since the car was so distinctive—with its unusual taillight design and out-of-state plates—there is almost no chance that Carter’s presence in the area was simply coincidental.

The case has retained a great deal of fascination with the public, and interest in it was renewed in 1999 with the release of the film The Hurricane, starring Denzel Washington. Rubin Carter himself went on to serve as the executive director of the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted until 2005, and often toured as a motivational speaker before succumbing to prostate cancer in 2014.

John Artis, for his part, pled guilty in 1987 of distributing a small amount of cocaine and receiving a stolen handgun, a charge for which he served six years. After his release, he seems to have kept a low profile, occasionally appearing on various talk shows to discuss issues surrounding the wrongfully convicted. He was reportedly with Rubin Carter when the boxer passed away. Artis himself died of an aneurysm in November of 2021, at the age of 75.

The debate continues to the present day.