Nearly two decades removed from the notoriously ghastly prostitute slayings perpetrated by Jack the Ripper, the year of 1907 would see the murder of a working girl in eerily similar circumstances. In more recent times, a few Ripper researchers have attempted to link the infamous Whitechapel killings with the much later case widely known in England as the Camden Town Murder, though the connection seems tenuous at best.

In 1907, Emily Dimmock, known as Phyllis among her clients, was just another twenty-three-year-old woman trying to make a living on the rough London streets around Camden Town. She had been born poor in a small village in Hertfordshire, and had spent most of her teenage years working as a maid in various households.

Upon moving to London when she was eighteen or nineteen years old, she began staying in a boarding house-slash-brothel run by a petty criminal by the name of John William Crabtree, and she subsequently took to working the streets to earn her keep.

But by the time 1906 rolled around, Emily was in something of a better situation. She was living in a flat on St. Paul’s Road with her nineteen-year-old common-law husband, Bert Shaw, and the couple hoped to get permission from his parents to legally marry sometime soon. As a condition of their marriage, Emily had agreed to give up prostitution and lead a respectable existence. Bert was not a wealthy man, but had a steady job working as an overnight chef on the Midland Railway.

Emily, though, despite the promise of domestic stability, still seemed restless and for some reason longed to go back to her old life of drinking in pubs and soliciting men. As her husband Bert worked all night, from four-thirty in the afternoon to eleven-thirty the following morning, Emily began stepping out in the evenings without his knowledge, frequenting the bars along Euston Road.

It was at one of these establishments, the Rising Sun, that she met with a young glassware designer by the name of Robert Wood on September 6th. Whether she had known him for a long time previously, as witnesses maintained, or whether this was their first meeting, as Wood himself claimed, would become a bone of contention later on in the sequence of events.

At any rate, Emily and Robert were sharing a drink together on Friday, September 6th, and at some point during the festivities, perhaps after Emily had gone, Robert took a postcard out of his pocket and wrote on it, “Phillis darling. If it pleases you to meet me at 8:15 at the Rising Sun. Yours to a cinder.” He signed the card “Alice,” to allay suspicion if the card happened to be seen by Emily’s husband.

Robert Wood mailed this postcard on either Sunday or Monday, and it apparently arrived at the Shaw household on or before the 11th of September. On the nights in between, Emily had been entertaining another client, a cook by the name of Robert Percival Roberts, but when Wednesday, September 11th arrived, she was seen at the Rising Sun and later at another pub called the Eagle in the company of Robert Wood.

The following morning, at around eleven a.m., Bert Shaw’s mother arrived at her son’s residence. Most sources claim that she was there in order to finally give Emily the news that she and Bert could marry with his parents’ blessing.

However, there was no answer to Mrs. Shaw’s summons, and the door to their flat was locked. The landlady of the building let Mrs. Shaw in so that she could wait in the common area for Bert to get home from work, which he did around half an hour later.

When Bert and his mother entered the ground-floor apartment, they were greeted by a gruesome sight: Emily Dimmock was lying naked on the bed, her throat slashed from ear to ear, and the room was painted in blood. Forensic examination would determine that Emily had likely been murdered in her sleep, at some point between three and six a.m.

It did not appear that anything had been taken from the flat, save for the house keys, though it looked as if it had been ransacked, and most of Emily’s postcard collection was scattered all over the floor. Two of Bert’s straight razors were found near the sink along with a few smears of blood on a towel, as though whoever had done the killing had tried to wash the blades and his hands before leaving the flat and locking up behind him.

The crime immediately caused a media sensation to rival the coverage of the Jack the Ripper murders back in 1888. The story had everything: a beautiful young victim, lots of scandalous sex, and salacious details about the sordid underbelly of early 20th century London.

Almost immediately, suspicion fell on glass artist Robert Wood, who had apparently been the last to see Emily alive. Bert Shaw had eventually come across the postcard that Robert had sent to Emily, and after an image of the postcard was published in the papers, the handwriting was quickly identified as Robert’s by his ex-girlfriend, Ruby Young.

Ruby also told police that even though she was not seeing Robert anymore, that he had come to her on the day following the publication of the postcard and asked her to tell the authorities that they still saw each other regularly on Monday and Wednesday evenings. Robert Wood was subsequently arrested and placed on trial.

On the surface, the case seemed fairly straightforward. The prosecution argued that on the evening of September 11th, Emily had met Robert Wood just as planned at the Rising Sun, after which they had gone to another pub, the Eagle, where they were seen by multiple witnesses. The couple had then repaired to Emily’s flat where they had sex. Emily had fallen asleep, and Robert had slashed her throat, cleaned himself up in the sink, searched the flat for the incriminating postcard, and then, failing to find it, let himself out into the dawn.

The evidence against Robert Wood began to stack up. Emily’s former landlord, John Crabtree, identified Robert as a man who had visited Emily a great deal when she still lived in the boarding house. This contradicted Robert’s own statement that he had met Emily for the first time on September 6th. Other witnesses likewise identified Robert as someone who had been seen with Emily in both the Rising Sun and the Eagle on multiple occasions prior to September 6th.

Additionally, a neighbor named Robert MacCowan claimed he had seen a man in the street near the Shaw house at around five minutes to six on the morning of the murder. This man, he claimed, walked with a distinctive gait: left hand held stiffly in his pocket, right shoulder jerking in time with his right footfall. Robert Wood, it was stated, walked in this particular manner.

These rather damning facts, combined with the testimony of Ruby Young, who claimed that Robert Wood had attempted to use her as an alibi for the evening of the murder, made the conviction of the young artist look ever more certain.

The case, however, wasn’t quite as unequivocal as it might have seemed. On the morning before she was murdered, for example, Emily received a letter in the post. She burned the letter after reading it, and only barely readable scraps of it were found in the fireplace by investigators. But Robert Percival Roberts, who admitted to spending three nights with Emily shortly before her death, testified that she had showed him the letter before she had burned it, and that it had read, “Dear Phyllis. Will you meet me at the bar of the Eagle at Camden Town 8:30 tonight Wednesday. -Bert.”

Emily’s common-law husband Bert Shaw was never a suspect in her murder, as he was provably at work in Sheffield at the time, but the letter seemed strange nonetheless. Did Emily have some other client who was named Bert who had met her that night and later killed her? Was “Bert” a pseudonym for some unknown person? Was Robert Percival Roberts misremembering the contents of the letter, or simply fabricating them to avoid suspicion falling upon himself? He was, after all, the second most likely suspect after Robert Wood, though he had a fairly solid alibi.

Robert Wood was lucky enough to be represented at the trial by one of the most celebrated litigators of the time, Edward Marshall Hall, who tore down most of the testimony against his client in a rather brilliant fashion. Robert Wood, it was argued, had only lied about his long association with Emily because he did not want his dying father to be upset by rumors about his dalliances with prostitutes. Further, on the night of the murder, Robert Wood had indeed spent some time with Emily at the Eagle, but immediately thereafter had gone to visit his father. A witness testified that Robert Wood had indeed arrived at his father’s home shortly before midnight, though Robert’s father himself was too sick to testify.

Edward Marshall Hall also made much of the fact that Robert Wood had only tried to secure an alibi from Ruby Young for the evening of September 11th, and not for the actual time of the murder, which was several hours later. The attorney pointed out that had Robert Wood actually killed Emily Dimmock, he certainly would have tried to account for his movements between the hours of three and six o’clock on the morning of September 12th, which he specifically did not.

Hall further pointed out that Robert Wood’s distinctive walk was not, in reality, particularly distinctive, and that several other men with similar gaits could be seen walking those streets to work every morning around that time. A boxer named William Westcott, in fact, testified that he possessed a walk like that described, that he had been in the area at around six that morning, and that perhaps it was him that the neighbor Robert MacCowan had seen.

Robert Wood actually did take the stand in his own defense, and though his demeanor didn’t seem to especially impress the jurors, the case for his innocence that Edward Hall built apparently did: Robert Wood was acquitted after only fifteen minutes deliberation, with even the judge giving the opinion that the prosecution had fallen well short of proving their case.

But if Robert Wood didn’t kill Emily Dimmock, then who did? Because of the nature of her profession, there remains the possibility that she simply ran into the wrong client on her way home that night, and the culprit was not a man of her former acquaintance at all.

It’s also certainly possible that Robert Percival Roberts could have done the deed, though both his friend and his landlady testified that he was at his own flat for the entire night of the murder.

There was also the elusive individual known only as “Scottie,“ mentioned by John Crabtree at the trial. Crabtree admitted that he did not know Scottie’s real name, but that years before, Scottie had come around the boarding house threatening Emily and himself with a straight razor on several occasions. Crabtree even claimed that Scottie had made reference to Emily ruining his life. This person was never identified.

Crabtree also mentioned another fellow named Robert Mackie, aka Scotch Bob, who used to spend a great deal of time with Emily. Though Mackie was investigated, it was at first thought that he was in Scotland at the time of the murder. However, later on it came to light that the dates he had given for being in Scotland were incorrect. The police never pursued him any further, regardless.

Two other witnesses at the trial, Mr. Sharples and Mr. Harvey, testified that they had seen Emily at around midnight on the night of her murder around Kings Cross, accompanied by a large man who was not Robert Wood. This man was likewise never identified.

One of the more bizarre hypotheses regarding the Camden Town Murder, and the one that allegedly connects it with the Jack the Ripper case, was that both the Ripper slayings and the killing of Emily Dimmock were perpetrated by the same man: renowned artist Walter Sickert.

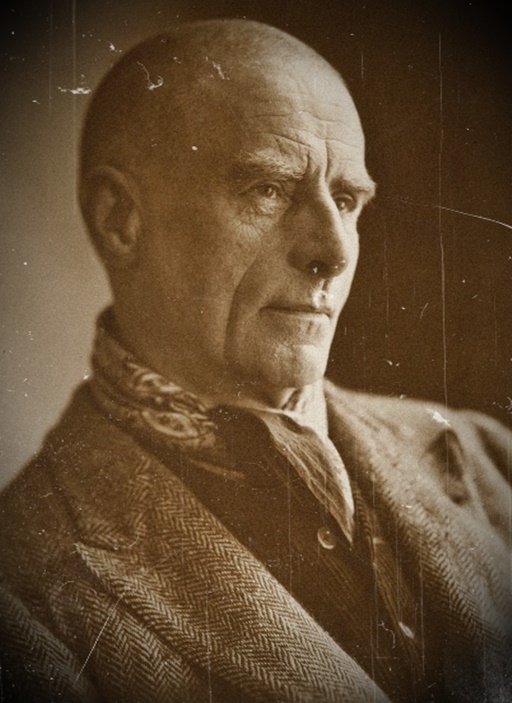

Though it is true that Sickert lived in the same general area as Emily and had an admitted fascination with her murder, the evidence implicating him in Emily’s case boils mainly down to a series of paintings and sketches that he made entitled “The Camden Town Murder,” all of which portrayed a theme of clothed men sitting next to or standing over naked women.

The conspiracy theories surrounding Sickert gained a huge boost in 2002 when crime writer Patricia Cornwell penned a book not only accusing him of being Jack the Ripper, but of killing Emily Dimmock as well. Cornwell claimed that many of Sickert’s paintings bore an uncanny resemblance to the Ripper’s crime scenes. She was later accused of destroying one of Sickert’s paintings while trying to obtain DNA to definitively finger him for the murders.

Most Ripper experts, however, doubt very highly that Walter Sickert was involved in either the Jack the Ripper case or the killing of Emily Dimmock, and in fact, it is also considered very unlikely that the crimes were committed by the same person. The death of Emily Dimmock, after all, occurred almost twenty years after the last known Ripper murder, and the modus operandi of the killer was not particularly similar. While the Ripper was known to enjoy disemboweling his victims and taking various organs as trophies, the murder of Emily Dimmock seemed comparatively quick and efficient, with no mutilation involved.

At this stage, it seems that the Camden Town Murder is just as likely to be solved as the Jack the Ripper slayings; that is to say, not likely at all.