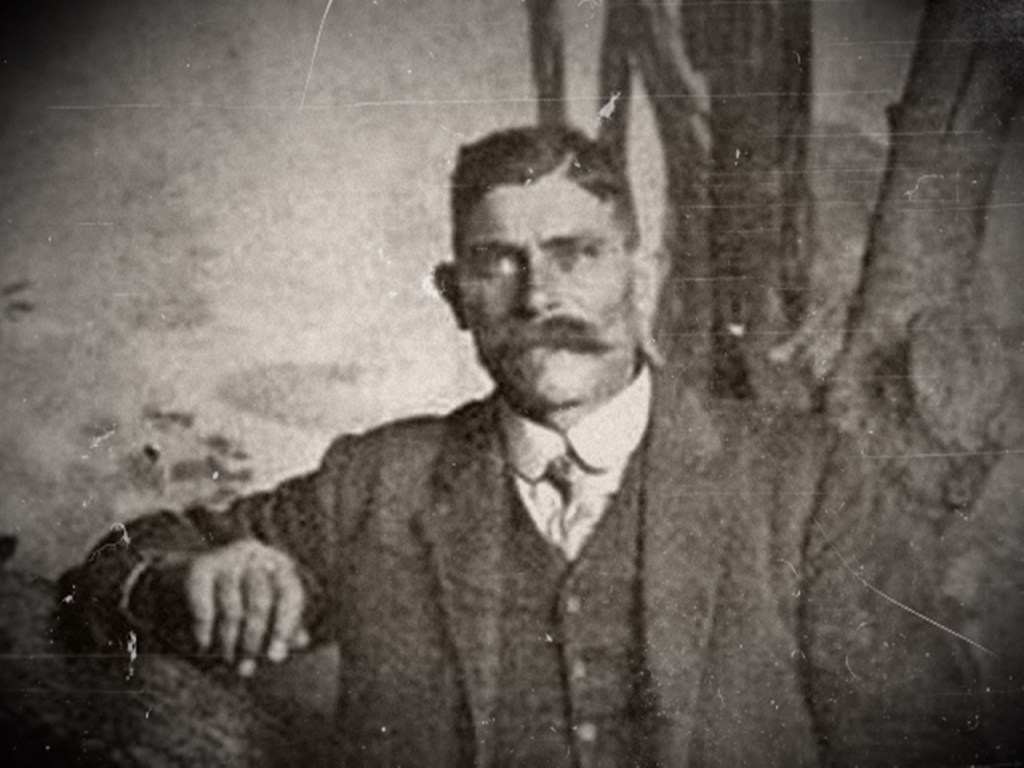

Wonnangatta Station was a lonely cattle ranch in a remote valley of the Victorian Alps in Australia, overseen by a widower named James “Jim” Barclay. Finding the need for the services of a cook and handyman in the latter part of 1917, James hired a man by the name of John Bamford, who had been born in England but had lived in the area for the previous two decades.

Labor was hard to come by, not just because of the station’s isolated location, but also because most men of working age were off fighting the First World War. John Bamford had a reputation for being argumentative and bad-tempered, but Jim Barclay didn’t seem to feel that his purported surliness would interfere with his work ethic. Bamford took up employment at the station on December 14th, 1917, and by all accounts, the two men got along just fine.

In fact, less than a week later, Jim and John traveled together to the nearest town of Talbotville, which was twenty miles from the station. The men were voting on a referendum concerning the introduction of military conscription. History did not record the way the two men voted, but it is known for certain that they voted the same way. After doing their duty, they stayed over in Talbotville at the home of their friend Albert Stout, and on the morning of December 21st, they mounted their horses and started back to Wonnangatta.

They evidently never made it.

A month later, on January 22nd, 1918, friend and neighbor Harry Smith dropped by the ranch to drop off some mail. He found Wonnangatta strangely uninhabited, the only sign of life a message reading, “Home tonight,” written on the kitchen door with chalk. Harry decided to hang around to see if Jim and John would return, but when they hadn‘t come back after two days, Harry returned to his home in Eaglevale, slightly concerned, but thinking that there must be a simple explanation for their absence.

A few weeks later, on February 14th, Harry again set out for the ranch. Neither Jim nor John had returned in the interim, for the mail that Harry had left was still sitting on the table, unopened. Even more alarmingly, Jim’s beloved dog Baron looked as though he hadn’t eaten in weeks.

Now certain that something was wrong, Harry made a brief search of the property, but turned up nothing of note. He stayed at the station overnight, and the next day headed for the nearby town of Dargo to report the men missing. He also sent telegrams summoning Arthur Phillips and Geoffrey Ritchie, the owners of Wonnangatta Station.

Arthur arrived at Harry Smith’s home in Eaglevale on February 23rd, accompanied by another man, Jack Jebb. The three made the trek to Wonnangatta and began an exhaustive search of the grounds.

Less than a quarter mile southeast of the house, near the banks of Conglomerate Creek, the search party stumbled across a skull poking out of the sand. Said skull was attached to the woefully degraded corpse of a man, who was identified as Jim Barclay because of the distinctive tobacco pouch and belt he wore. It appeared that someone had attempted to haphazardly bury the body, but that dingoes had dug it out again shortly afterward and had their way with it. Arthur Phillips summoned the police.

Because the ranch was so remote from civilization, it took several days for officers to arrive, but when they did, they wasted no time investigating the scene, sending Jim’s remains to Mansfield hospital eighty miles away for an autopsy, and discovering a few clues that led them to formulate a somewhat straightforward solution to the mystery.

Inside the homestead, police discovered Jim’s shotgun in his bedroom, and were able to determine that it had been fired fairly recently. Both Jim’s and John’s bedrooms were in some disarray, though no blood was found inside the house. Officers also noted that some of John’s belongings were missing, including his suit, his saddle, and his horse.

By far the strangest piece of evidence discovered at the ranch was the pot of pepper in the kitchen that contained significant amounts of strychnine.

After gathering all the information they could, the officers headed back to Mansfield. On their return journey, they happened to come across John Bamford’s missing horse, which was running free on the plains wearing neither saddle nor bridle.

The autopsy of Jim Barclay’s body revealed that the cause of death had been a single shotgun blast to the back. From the condition of the remains, it was believed that Jim had died sometime between December 21st and January 4th, indicating that he had probably been dead for at least three weeks before his body was recovered. Despite the strychnine found at the ranch, it did not appear that James had been poisoned.

Naturally, because John Bamford was nowhere to be found and because his suit and a few of his belongings were missing, police proceeded on the assumption that John had killed his employer following an argument, then changed into his suit and rode off into the wilderness. So thinking, the government offered a reward of £200 for any information, and a statewide manhunt for John Bamford began.

But the outcome of the Wonnangatta Station murder was not to be nearly as clear as it initially seemed, though complicating developments would not reveal themselves until much later in the year, in autumn, when a strange new wrinkle appeared in the case.

John Bamford was still being sought for the shooting death of his employer, but by the late fall of 1918, police were no closer to tracking down their prime suspect. Their only lead so far had been a confession from a man who turned himself in for the murder, claiming to be John Bamford. The man had been arrested, but was released when it was discovered that he was actually a transient named James Baker who suffered from a mental illness.

In the early days of November, Harry Smith was accompanying a Constable Hayes and two other men on a search of the Howitt Plains, about twenty miles away from Wonnangatta Station, and somewhat near where John Bamford’s horse had been found back in February. Coming across a hut, the men noticed a boot sticking out of a pile of logs stacked on the property. Upon moving the logs, it was discovered that the boot was worn on the foot of the corpse of a long-dead John Bamford.

A post-mortem was duly performed, at which it was determined that John had been killed with a single bullet to the head. And now that the only suspect in Jim Barclay’s slaying had also turned up dead, police were quite at a loss to explain exactly what had befallen these two men in the remote Australian valley.

Many different theories were considered, including one where John Bamford actually had killed Jim Barclay, but then was later killed himself by Barclay’s friends in revenge. Alternately, some speculated that both men had been murdered by thieves, though the fact that nothing of particular value was taken from Wonnangatta Station tended to cast doubt on this particular hypothesis.

Also throwing theorizers for a loop was the niggling detail of the strychnine found in the kitchen at the ranch. Since neither Jim nor John appeared to have been poisoned, the presence of the strychnine in the pepper pot remained a frustrating anomaly.

Some suspicion was even cast upon Harry Smith, the friend and neighbor who had initially alerted police to the men’s disappearance and who was present when both bodies were discovered. Few took this allegation seriously, however, as Harry apparently had no motive, and he was never charged, though some felt that he knew more about the crime than he let on.

Some time afterward, James Barclay Jr., son of one of the murdered men, went to work for Harry Smith in Eaglevale, and remained employed there for many years. Harry Smith passed away in 1945, and if he knew anything about who killed the two men at Wonnangatta Station, he evidently took the knowledge with him to his grave.

However, in the 1970s, James Barclay Jr. was interviewed for a book about the ranch’s history, and though he seemed rather ambivalent about the enigma surrounding the death of his father, stating that everyone involved with the crime was dead and therefore beyond justice, he intriguingly referred to “both the murderers” in a rather offhand way. This comment was never expanded upon, and it remains a mystery whether James Jr. was aware of the identity of the killer or killers.

The case is still unresolved, more than a century later.