In February of 1945, a horrific murder in a sleepy English village would prompt furtive whispers about witchcraft, black magic, and occult sacrifices.

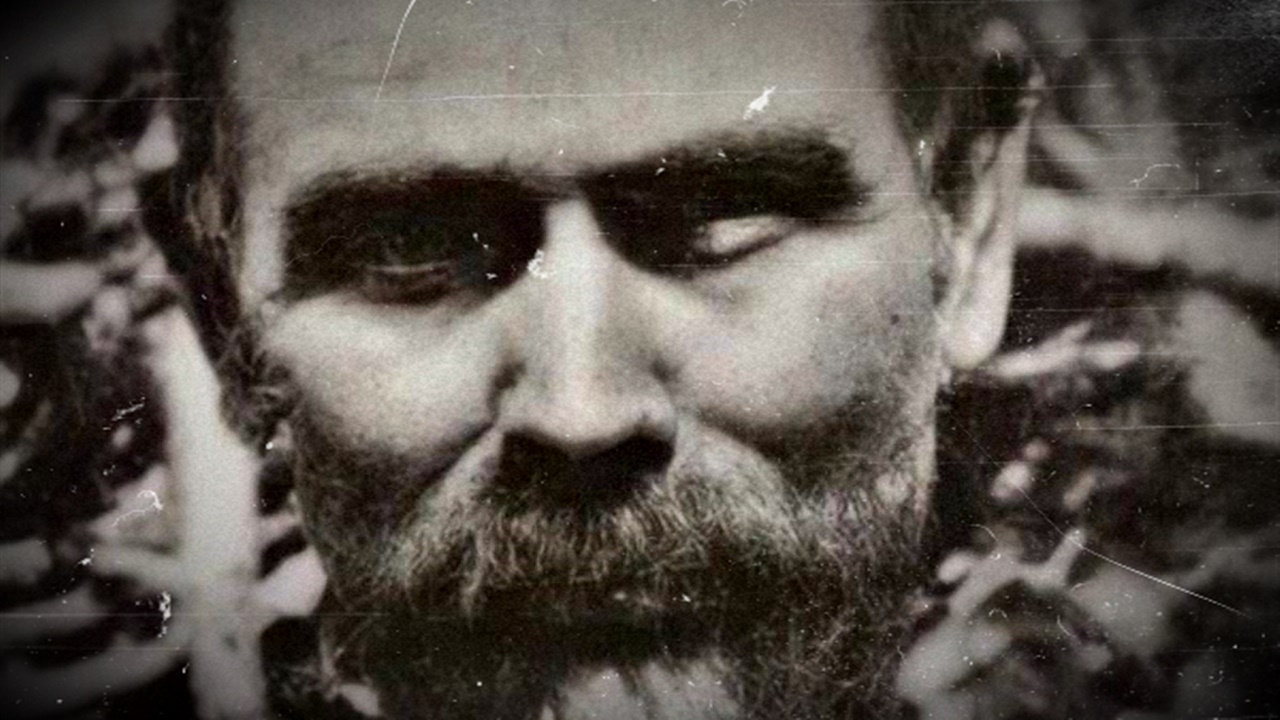

Charles Walton was a 74-year-old farm laborer who had called the little town of Lower Quinton home for his entire life. He lived in a modest cottage with his niece, Edith Walton, who he had adopted three decades earlier, when she was just three years old.

On the morning of St. Valentine’s Day, 1945, Charles set out at around eight a.m., as he usually did, heading for a nearby farm called The Firs, owned by a man named Alfred John Potter. Charles had been working for Potter for about nine months at this point, mostly cutting hedges on the property, which is what this particular day’s work entailed. To this end, Charles carried with him not only his trusty walking stick, which he used due to his rheumatism, but also his pitchfork and his billhook. Before the day was out, these three implements would be utilized for something far different than their intended purpose.

At four o’clock that afternoon, Charles’s niece Edith became concerned when Charles had not arrived home from work. She knew her uncle to be a staunch creature of habit, and it was very unlike him to remain in the fields this late in the day. When he still hadn’t arrived home after another couple of hours had passed, Edith rallied a neighbor named Harry Beasley as well as Charles’s employer Alfred Potter, and went out to look for him.

Because Potter knew the area where Charles had been cutting hedges that day, it didn’t take very long before the trio found out why the old man had failed to come home. Under an oak tree near where Charles had last been seen, they found the old man’s body. He had been bashed in the head with his own walking stick, which was found about a yard away, flecked with bits of flesh and hair. He had also been nearly beheaded by his own billhook, which some later reports stated had been used to carve a cross in his chest. The billhook had severed his trachea, and still remained, jutting out of the gaping wound in his neck.

Most horrifically of all, the old man’s body had been pinned to the ground by his pitchfork, the tines of which had been pushed through his throat so forcefully that it took two large men to free the tool from the hillside beneath the corpse.

A neighbor named Harry Peachey came by shortly after the body was discovered, and Harry Beasley sent him to fetch the police. Subsequently, Beasley accompanied Edith back to her cottage, leaving Alfred Potter at the scene to wait for investigators. PC Michael James Lomasney arrived at a little past seven that evening, followed by officers from nearby Stratford-upon-Avon.

Alfred Potter told police that he had been at the College Arms pub with his friend Joseph Stanley that morning, and had left there around noon. He claimed that as he crossed the field, he had seen Charles Walton at work, about six hundred yards away. He further stated that he had managed the farm known as The Firs for five years, and that he had known Charles Walton for at least that long, calling him a relatively “inoffensive type of man.” Indeed, though Charles Walton had a reputation of being something of a loner, there did not appear to be any particular dislike for him in the village of Lower Quinton, and seemingly no reason at all for someone to murder him so viciously.

An autopsy estimated that Charles Walton had been killed somewhere between one and two o’clock in the afternoon. Robbery could not be completely ruled out as a motive, as Charles’s pocket watch was thought to be missing. At first, however, investigators speculated that the elderly farmhand had either been the victim of a wandering lunatic, or perhaps an Italian POW from one of the minimum-security labor camps in the area; one of these men had reportedly been seen near the murder site with blood on his clothes.

Only two days after the murder, the famed Chief Inspector Robert Fabian of Scotland Yard arrived in the village, accompanied by his partner, Detective Sergeant Albert Webb. The Italian-speaking Detective Sergeant Saunders was also summoned to investigate the POW angle, though it was quickly determined that although a few of the Italian prisoners had been seeing a play nearby in Stratford on the day of the murder, there was no evidence to suggest that any of them had been responsible for the brutal slaying. The man whose clothes had been covered in blood was found to have simply been poaching for his dinner; the blood belonged to a rabbit.

Another suspect who was considered and eliminated was Charles Walton’s best friend George Higgins, who had actually been working in a field very close to where Charles had been murdered on the fateful day. However, George Higgins was determined to be too old and too ill of health to have inflicted the grievous wounds, and further, had absolutely no motive for killing his friend of many years.

Probably the most likely suspect, though, at least according to Robert Fabian, was Charles Walton’s employer, Alfred Potter. Fabian noted several inconsistencies in statements that Potter gave to police over the course of the investigation. For example, three days after the murder, Potter claimed that after leaving the pub, he had gone straight home to attend to one of his heifers that had fallen into a ditch, and that he had arrived there at about twelve-forty in the afternoon.

However, five days after he made this statement, he contradicted this claim by saying that he had actually gone home that afternoon, read the paper in his kitchen for a few minutes, then helped his neighbor Charles Batchelor pulp mangolds. Even more suspiciously, the heifer Alfred Potter had referred to in his first version of events was later discovered to have drowned in the ditch the day before the murder.

Potter’s stories and behavior were erratic in other ways as well. He claimed that when he had seen Charles Walton working in the field, for instance, he explicitly told police that Charles Walton was in his shirtsleeves, which he said struck him as unusual. However, when the body was found a short time later, Walton was wearing a jacket. And after PC Lomasney mentioned the fact that police were hoping to get fingerprints off the murder weapons, Potter made a point of telling investigators that he had touched all the implements himself, supposedly in the course of checking whether Charles Walton was still alive. Unfortunately, though, no fingerprints, either Potter’s or anyone else’s, were found on any of the murder weapons.

Though investigators had their suspicions about Potter, they were hamstrung by the fact that he had no apparent motive for killing the old man, much less in such a gruesome and labor-intensive fashion. Though it was initially hypothesized that the two men had perhaps had a falling out about unpaid wages, interviews with other employees of Potter’s, as well as people who had had other business dealings with him, suggested that Potter was actually benefiting a great deal by having Charles Walton work for him, as he was routinely overstating the number of hours the old man worked to the owners of the farm, then paying Charles and pocketing the difference.

And even Robert Fabian had to admit that despite all the intensive interrogations the police put Potter through, the man kept his cool, and even though his story had changed in its various details, the inconsistencies could have been simply the product of faulty memory or confusion engendered by the investigative process itself.

Having exhausted all the more mundane lines of inquiry, police began to consider a far more intriguing motive for the killing, a motive which had been bubbling under the surface ever since the beginning of the investigation. Since Charles Walton had been killed in a seemingly ritualistic fashion near Meon Hill, once the site of an Iron Age hill-fort and long rumored to be a meeting place for witches or Druids, some began to speculate that Charles Walton had been murdered either as a sacrifice to ensure a better harvest, or because he himself was believed to be involved in witchcraft.

There were several other aspects of the slaying that bolstered the witchcraft theory. The murder occurred on St. Valentine’s Day, which on the old Julian calendar corresponded to Candlemas or the Celtic festival of Imbolc, known for being a day of sacrifice. On that particular year, February 14th also happened to fall on Ash Wednesday.

Even more to the point, Detective Superintendent Alex Spooner of Warwickshire CID showed the Scotland Yard investigators a book entitled Folklore, Old Customs and Superstitions in Shakespeare Land, in which he had highlighted a couple of passages. One of these passages described the 1875 murder of a woman named Ann Tennant, who had been killed with a pitchfork by a man named James Heywood, who suspected that she was a witch. While in truth the woman was simply stabbed with a pitchfork in the center of town and later died from her injuries, the commonly known folklore surrounding the tale had Ann Tennant pinned to the ground with the pitchfork and slashed in the throat with a billhook, as well as having a cross carved into her chest.

The other passage told the story of a young boy, also named Charles Walton though likely not the same person, who had in 1885 seen the recurring apparition of a black dog and a headless woman that portended the death of his sister. Indeed, phantom black dogs were a very common legend in Warwickshire, and Robert Fabian himself even claimed to have seen one lurking around Meon Hill as he was working on the case.

Anthropologist Margaret Murray, who had also speculated about a witchcraft motive in the earlier and infamous Bella in the Wych Elm murder, likewise believed that Charles Walton had been killed as a ritual sacrifice. It was discovered, in fact, that the crops in Lower Quinton had failed the previous year, and that perhaps one of the superstitious townsfolk felt that an infusion of human blood into the soil might help turn things around.

There were also allegedly rumors circulating that Charles Walton himself was a little too versed in plant lore for comfort, that he could tame wild dogs with his voice or attract birds to eat out of his hands, or even that he dabbled in black magic, cursing neighbors’ cattle and blighting local fields with his army of natterjack toads.

Despite an intensive inquiry that saw investigators questioning all 493 of the rather reticent residents of Lower Quinton, no definitive evidence could ever be found linking anyone in particular to the ghastly crime, and as the years passed, the occult connection became ever more pronounced, so much so that the case is still known in England as “The Witchcraft Murder.”

In later years, Robert Fabian, who would become renowned as a crime writer and as the inspiration for the popular BBC drama series of the 1950s, Fabian of the Yard, seemed to lend credence to the black magic motive for the killing when he wrote in 1970, “I advise anybody who is tempted at any time to venture into Black Magic, witchcraft, Shamanism—call it what you will—to remember Charles Walton and to think of his death, which was clearly the ghastly climax of a pagan rite. There is no stronger argument for keeping as far away as possible from the villains with their swords, incense and mumbo-jumbo. It is prudence on which your future peace of mind and even your life could depend.”