As the autumn of 1982 began to descend, an alarming series of tragedies would begin to unfold in the suburban communities in and around Chicago, Illinois. The aftermath of the incident—which would leave seven people dead and an entire nation terrified and paranoid—would lead to sweeping changes in U.S. law, as well as a significant alteration of the culture itself.

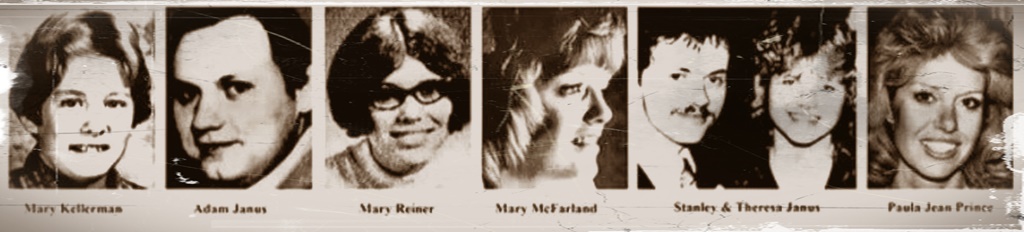

On September 29th, 1982, twelve-year-old Mary Kellerman woke up in her Elk Grove Village home with mild cold symptoms. Her parents gave her a single extra-strength Tylenol capsule, the type that contained acetaminophen. Less than an hour later, the little girl was dead.

About seven miles away, in the suburb of Arlington Heights, a twenty-seven-year-old postal worker named Adam Janus also passed away, from what at first was believed to be a sudden and massive heart attack. Upon hearing of the death, Adam’s family members descended on his home to offer mutual support to one another. While gathered there, Adam’s twenty-five-year-old brother Stanley and Stanley’s nineteen-year-old wife Theresa both swallowed Tylenol capsules from the bottle in Adam’s medicine cabinet. Stanley died later that afternoon, while Theresa lingered in the hospital for two days before also expiring.

The following few days would see three more suspicious deaths in the area: thirty-five-year-old Mary McFarland, thirty-five-year-old Paula Prince, and twenty-seven-year-old Mary Weiner. By this stage, September had given way to October, Adam Janus’s cause of death had been found to be cyanide poisoning, and authorities were beginning to link all these mysterious crimes to bottles of extra-strength Tylenol.

Sure enough, once the capsules from all of the victims’ households were tested, it became clear that someone was adulterating random packages of the over-the-counter medications with potassium cyanide. Thorough searches of retail locations selling the medicine in the Chicago area produced a further three bottles of poisoned capsules still available for purchase at local drug stores.

Police, as well as Johnson & Johnson—the manufacturers of Tylenol—reacted with admirable swiftness to the crisis, alerting the media, driving the streets with bullhorns, even going door to door in Chicago neighborhoods to get warnings out and confiscate bottles of the offending painkillers. Johnson & Johnson immediately issued a recall of the over thirty-one million bottles of extra-strength Tylenol in U.S. circulation, and instantly ceased all advertising of the product as well.

An investigation into the source of the tampering soon ruled out adulteration at the manufacturing level, since the tainted bottles had all been produced by different pharmaceutical factories. And because the deaths all occurred around the Chicago area, it was deduced that the killer was stealing or purchasing bottles of Tylenol from various retail outlets, tampering with the capsules, then sneaking them back onto store shelves. Indeed, security footage of victim Paula Prince in one of the affected stores showed an unidentified, bearded man following quite closely behind her as she shopped. Though detectives sought this man as a person of interest, they were never able to locate him.

One suspect who helpfully announced himself, however, was James William Lewis, who in October of 1982 sent a letter to Johnson & Johnson claiming responsibility for the poisonings and demanding a one million-dollar ransom to cease his activities. But Lewis lived in New York City, not Chicago, and police were unable to find any further evidence linking him to the product tampering, though he was charged with extortion and ended up serving thirteen years in prison; he was released in 1995.

Another man named Roger Arnold was also investigated, and though he was cleared, the media frenzy that followed in the wake of his questioning would end up having tragic consequences. Arnold blamed an acquaintance of his, Marty Sinclair, for allegedly telling police that he kept potassium cyanide in his home, and in 1983 he decided to kill Sinclair for betraying him. Unfortunately, Arnold instead shot another individual who only resembled Sinclair: John Stanisha, who was completely uninvolved with the incident and didn’t know either man. Arnold was later convicted of second-degree murder and served fifteen years. He died in 2008.

Other persons of interest included rampage poisoner and shooter Laurie Dann from Winnetka, Illinois, as well as notorious Unabomber Ted Kaczynski, but neither of these leads have so far borne any fruit.

In a heartbreaking coda to the case, several copycat incidents took place in the years following the original outbreak, including additional deaths in New York, Texas, and Washington state.

The panic and uncertainty surrounding the entire affair led to many notable changes in the United States, including a 1983 law making it a federal offense to tamper with consumer products. Johnson & Johnson and other large corporations also worked together with law enforcement to develop more stringent quality controls at the point of product manufacture, and most famously introduced much more tamper-resistant packaging, including foil induction seals and the replacement of the capsule drug format to the now-ubiquitous solid pill “caplet.” Consumer experts have credited Johnson & Johnson’s honest, immediate reaction to the tragedy and their willingness to work with law enforcement to improve product safety around the country for their almost unbelievable return to market dominance less than a year after the poisonings occurred.

The investigation into the Chicago Tylenol Murders was reopened in 2009, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the event, and shortly afterward, original suspect and ransom letter writer James William Lewis willingly gave a DNA sample to the FBI, as did his wife. Federal agents also searched the Lewis home in Massachusetts, but have not released their findings to the public at this writing.