Marianne Schmidt had moved with her family to Melbourne, Australia from her native Germany back in 1958. By 1965, she was fifteen years old, living in Sydney, and had become inseparable best friends with her fifteen-year-old neighbor Christine Sharrock, who lived next door with her grandparents.

It was January, the height of the Australian summer. For the previous few weeks, Marianne and Christine had been spending a great deal of time at the beaches in Cronulla, which was at the time the only seaside town easily accessible from their homes by train. Sometimes they would go with Marianne’s mother and siblings, and often they would take along food for a picnic.

On January 11th, they embarked on just such an excursion. They had actually planned the trip for the previous day, but rain had kept them indoors. The Schmidt brood had been left home alone, with Marianne in charge; their father had died of Hodgkin’s disease the previous year, and their mother was in the hospital undergoing an operation.

That morning, the two teenaged girls boarded a train bound for Cronulla, accompanied by the younger Schmidt children: Norbert, Peter, Trixie, and Wolfgang. They arrived at the train station near the beach at around eleven a.m. Marianne had brought along sandwiches and drinks; Christine apparently stopped along the way and purchased something different to eat. She might have also brought along alcohol, though this is not known with any certainty.

The day was exceptionally windy, so much so that the beach was closed. Undeterred, the party walked to the south end of the beach and settled themselves in an area somewhat protected by rocks. Eight-year-old Wolfgang went swimming in the shallows while Marianne watched over him, then they returned to the rocky picnic area and ate their sandwiches.

According to later statements given to police by the four younger children, it was at around this point that Christine Sharrock went off on her own for a brief time. No one knows where she went or what she did, but it’s almost certain that during the period for which her whereabouts were unaccounted for, she ate something separately from the rest of the group—something containing celery and cabbage—and also consumed an alcoholic beverage.

Wolfgang Schmidt later stated that at around this same time, he saw a teenaged boy standing in the shallows, hunting crabs. The child’s description of the boy differed with each telling, with hair color varying between sandy blond and brown, and some iterations claiming the boy carried a homemade spear, or perhaps a fishing knife in a sheath, or both. Wolfgang seemed quite sure, however, that the boy he saw was shirtless, with light gray pants, and carried a blue towel slung over one shoulder. He was also fairly certain that he saw the boy two more times later in the afternoon, once walking with Marianne and Christine, and once walking by himself.

After Christine came back from her mysterious jaunt, the group decided to walk some way down the shoreline to explore the Wanda Beach sand hills. They reached a point about four-hundred yards from the Wanda Beach Surf Club, and by that time the children were starting to complain about the ferocious winds blowing sand into their eyes and whipping their hair and towels around. The six of them temporarily took shelter behind one of the dunes.

It was a little past one in the afternoon. Marianne told her siblings to stay where they were, and she and Christine would walk back to the south end of the beach to retrieve their bags, then come back for the children and start to head back home. Marianne left her small transistor radio to entertain the young ones in her absence.

However, as soon as Marianne and Christine crested the dune, they began walking north, farther into the sand hills. Peter told them they were going the wrong way, but evidently the girls just laughed, made a dismissive comment, and kept going.

It was at this point, according to some sources, that Wolfgang claimed that he saw the unidentified teenaged boy walking with Marianne and Christine. Wolfgang stated that the girls seemed to be trying to get away from him, and that he was yelling at them to tell him their names, though the girls were refusing to answer.

Other than the killer, the last person known to have seen the girls alive was Dennis Dostine, a local firefighter who was strolling through the area with his son. He spotted Marianne and Christine walking about eight-hundred yards north of the Wanda Beach Surf Club. He noticed that they appeared to be moving quickly and looking behind them every few steps, as though they thought they were being followed. Dostine, however, did not see anyone behind them, and subsequently went about his business.

Meanwhile, the four Schmidt children were still biding their time in the lee of the sand hill, waiting for their big sister to return. By the time five p.m. rolled around, though, they knew they would have to be heading back soon, or they would miss the last train of the day. Frightened and confused, the young siblings made their way back to the rocky area at the south end of the beach where they had left their bags, and from there walked to the train station to board the six p.m. train back home. Upon arriving in Sydney two hours later, the children told Christine’s grandmother what had happened, and she reported the girls missing at eight-thirty p.m.

On the following day, January 12th, Peter Smith and his nephews were taking a walk through the sand hills on Wanda Beach when they spotted what they at first thought was a store mannequin partially buried in the dunes. Peter approached it and wiped at the area around the hand, and then realized with horror that he was looking at a human body. He quickly retreated to the surf club and phoned police.

When authorities arrived and began digging out the remains, they were confronted with not one body, but two. The dead girls were almost immediately assumed to be Marianne Schmidt and Christine Sharrock, who had been reported missing the night before.

Marianne, who had been found first, was lying on her side. She had been stabbed fourteen times—one of these wounds penetrating her heart—and had her throat slashed so deeply that she was nearly decapitated. Christine was discovered lying face down, her head touching the bottom of Marianne’s foot. She had also been stabbed multiple times, and had the back of her head bashed in with a blunt instrument.

Both girls had their bathing suits partially cut off them, and there were traces of semen found on the bodies, though both girls’ hymens were still intact, leading police to believe that they had been killed during the course of an attempted rape. Because of a long drag mark discovered in the sand nearby, it was thought that the killer had attacked Marianne first, at which point Christine had tried to run away, but was subsequently chased, caught, and killed before being dragged back to the site and partially buried in the dune.

Investigators sifted through tons of sand around the crime scene, hoping to turn up a clue, but the murder weapons were ultimately never found. Though a bloody knife blade did turn up during the course of the search, it was never able to be connected with the murders of Marianne and Christine.

It was during the autopsy that Christine was found to have a blood alcohol level of .015, roughly equivalent to a glass of beer. No alcohol was found in Marianne’s system. It is not known whether Christine had brought alcohol along on the trip and had gone off by herself to drink it, or if she had gone off to meet someone who had provided it for her.

It is also not known whether the girls had specifically gone to Wanda Beach that day to meet anyone in particular, perhaps including the teenaged boy reported to police by Wolfgang Schmidt. According to the girls’ families and friends, both Marianne and Christine were quite shy and well-behaved, and were not known to be dating anyone. Neither of their diaries mentioned anyone special either, though both girls were enamored of the surfer lifestyle and sometimes mentioned crushes they had on boys they’d seen at the beach.

Lending some credence to the theory that the girls were murdered by someone they knew was the fact that Trixie told police that the girls were talking to a teenaged boy on the train on the morning of January 11th. This boy, however, was seen to get off the train at the Redfern station, and did not appear to have transferred to the Cronulla-bound train with the girls and the children.

Another interesting fact was that Christine’s grandmother recalled that the day before the girls’ fatal trip, Christine had made an offhand comment about how she was looking forward to walking through the Wanda Beach sand hills again. The dunes at that time, because of their seclusion, were a haven for nude sunbathers and other people pursuing illicit sexual encounters, so Christine’s grandmother allegedly warned the teenager against wandering around there, a warning which seems to have gone unheeded.

In fact, one individual who was sought by police as a possible suspect or witness to the crime was a man who several women on the beach reported had approached them and made offensive sexual advances. Though this man’s name was never established, one of the lifeguards at Wanda Beach confirmed that the man had been escorted off the beach on at least one occasion due to his constant harassment of female beachgoers. This man, described as older and somewhat balding, was never located for questioning.

Likewise, the shirtless teenager with the blue towel who had allegedly been seen three times on the day of the girls’ murder was never identified. There were, however, several other persons of interest that investigators had their eye on, though it should be noted that none of them matched Wolfgang’s description of the spear-or-knife-carrying “surfer” boy.

One of these suspects was a man named Christopher Wilder, who would later become rather well-known in the United States as the so-called Beauty Queen Killer, responsible for eight murders and several attempted murders in 1984. Before he fled to the U.S. in 1969, however, he had been convicted of participating in a gang rape on a beach in Sydney, Australia in 1963. He died in 1984 during a skirmish with police, and it is still unknown whether he was responsible for the Wanda Beach murders.

Another rather strong possibility was convicted child killer Derek Percy. In 1969, Percy was given life in a psychiatric prison for murdering a child on a Victoria beach, but police suspected that he may have committed several other murders for which he was never tried. It is almost certain that Percy was in the Wanda Beach area at around the time of Marianne and Christine’s murders, and it seems significant that his grandmother, with whom he sometimes stayed, lived less than a mile away from Marianne and Christine’s homes, but there was never enough physical evidence to definitively connect him to the crime. He died in prison in 2013, denying his involvement until the end of his life.

Slightly less likely a suspect was another convicted murderer, Alan Bassett. He had been given a life sentence in 1966 for killing nineteen-year-old Carolyn Orphin, though he was released from prison in 1995. Oddly, the thing that drew attention to him in regards to the Wanda Beach case was a painting he gave to detective Cec Johnson. In this landscape painting, Johnson believed, Bassett had inserted details about the crime that only the killer would know, such as the particular configuration of the blood found on the grass at the scene; what appears to be a partially buried female body with one hand prominent; and a broken knife blade.

Most investigators, however, did not find the painting to be all that compelling as evidence. Following his release from prison, Bassett willingly gave police a DNA sample to compare to partial DNA extracted from cold case evidence in the Wanda Beach murders, but the results of this comparison have not been made available to the public.

In fact, though the case was reopened in 2012, some DNA samples have since been lost. Despite the setbacks, investigators remain optimistic that the crime will eventually be solved. A large reward is still available for any information leading to the conviction of the killer.

Only a little over a year following the murders of Marianne Schmidt and Christine Sharrock on Wanda Beach, another devastating and multi-victim crime would rock Australia, and even though the case is technically classed as a disappearance, as no bodies were ever found, the vanishing and probable murder of the Beaumont children was a significant milestone in Australian social culture, and might have had links not only to the Wanda Beach case, but also perhaps to other murders that took place later on.

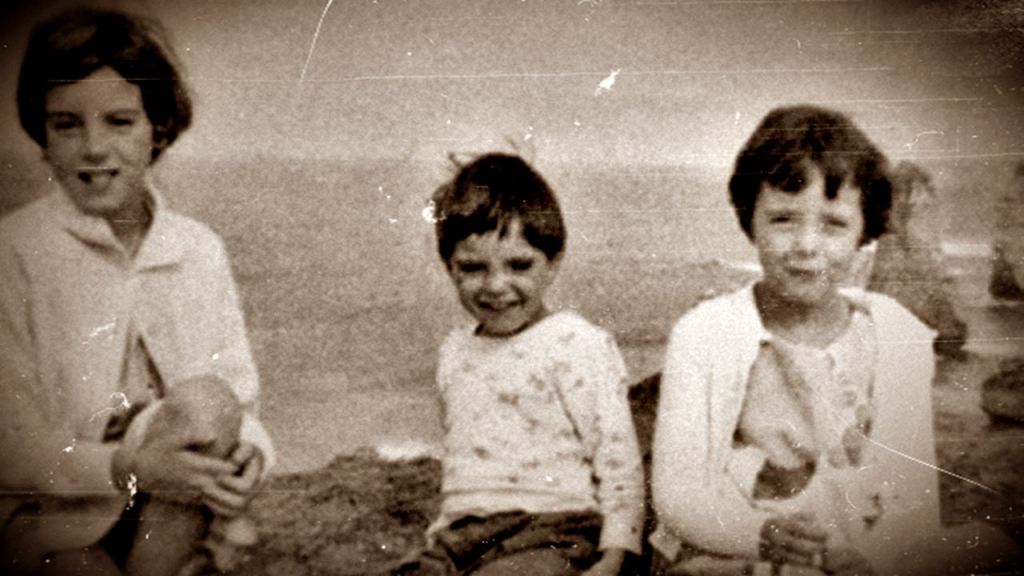

It was Australia Day, January 26th, 1966. The three Beaumont children—Jane, Arnna, and Grant, who were nine, seven, and four years old, respectively—planned to spend the early afternoon at nearby Glenelg Beach, as they had on the previous day. Incidentally, the beach where the children often played was very near the site where the infamous Somerton Man was found dead back in 1948.

The beach was not very far from the home that the children shared with their parents, Jim and Nancy, and ordinarily they would have simply ridden their bicycles. However, Nancy Beaumont, concerned about the heavy traffic due to the holiday, and mindful that it was far hotter outside than usual, bid the children to take the bus instead. She handed Jane, the oldest, about eight shillings for bus fare and snacks, and sent the children on their way at around ten in the morning, not thinking a single thing about it.

Jane, Arnna, and Grant were expected home on the two o’clock bus, and though Nancy waited for them at the stop, the children failed to appear. She didn’t panic at first, as she thought perhaps they had just lost track of time or missed their bus, but by the time her husband Jim came home from work later that afternoon, Nancy was frantic and begged Jim to drive down to the beach and look for them.

Jim traveled up and down the route the bus would have taken and scoured the beach, looking for his missing children. When he couldn’t find them, he drove back to the house and picked up Nancy so that she could help in the search. But all their efforts were in vain; the children were simply gone. Dismayed, they contacted police at around seven-thirty p.m.

As investigators began to trace the movements of the three children that day, it came to light that there had been several witnesses who had seen Jane, Arnna, and Grant in the area that morning. The Beaumont children were local, and frequented that particular beach, so many of the other beachgoers and merchants knew them by sight.

One witness was the postman, who initially stated that he had seen the children walking hand-in-hand and laughing down the main street at three in the afternoon. Authorities at first found this strange, as the children would have known they were an hour late getting home and presumably wouldn’t have been casually strolling down the road, unconcerned about getting in trouble with their mother. However, the postman later recalled that perhaps he had seen the children at the beginning of his route, not at the end, which would have placed them on the main street at around eleven a.m., a far more likely scenario.

Much more ominous, though, was the testimony of at least one woman who had been on the beach that morning and knew the children somewhat. She stated that she had seen Jane, Arnna, and Grant in the company of a suntanned blond man in his mid-thirties with an athletic build, dressed in dark blue Speedos with a white stripe. This man was playing with the children around the fountain near the edge of the beach that people used to wash sand off their feet. The witness reported that the children were completely relaxed and seemed to be enjoying the man’s company, as though they knew him rather well.

The woman also stated that the man had approached and asked her about “our clothes,” referring to his and the children’s clothing, and told her that he thought someone might have stolen something from among the possessions they had left on the beach. The witness further asserted that the man had at one point been helping Jane get dressed, which struck her as odd, as at nine years old, Jane was quite capable of dressing herself. The woman also knew Jane well enough to know that the girl was rather shy and reluctant to let strangers near her, let alone let them help her get dressed.

From this testimony, it was hypothesized that the man had befriended the children on a prior visit or visits, and slowly began gaining their trust. Strengthening this theory was the fact that Nancy Beaumont remembered an offhand remark that seven-year-old Arnna had made a few days before the disappearance; namely, that Jane had “got a boyfriend down the beach.” At the time, Nancy assumed that Arnna was talking about a playmate of a similar age, and hadn’t attached any significance to the comment.

At a little past noon, according to a shopkeeper along the beach who had also seen the children on several occasions, Jane came into his bakery and bought three pasties and a meat pie, paying with a one-pound note. The merchant was certain that the children had never bought a meat pie from his shop before, and after speaking to the children’s mother, police assumed that the man who was seen with the children had given Jane the money, as Nancy had only handed Jane eight shillings in coins.

The three children were spotted leaving the beach in the company of the mysterious man at around twelve-fifteen p.m., and subsequently vanished.

Dubious sightings of the Beaumont children would be reported to authorities for about a year following the disappearance, but none could ever be substantiated. In fact, a few months after the children went missing, a woman called police and told them that on the night of January 26th, she had seen a man, two little girls, and a little boy entering a house nearby that she had previously thought to be abandoned.

Later that evening, she stated, she had seen the little boy walking down a street alone, only to be pursued by the man, and roughly snatched up and carried back to the house. The following day, the witness alleged, the house appeared empty again. Investigators questioned why the woman had not reported this tip earlier, but at any rate, a follow-up investigation of the property yielded no evidence.

The disappearance of the Beaumont children, coming so soon after the horrific slayings of the two teenaged girls on Wanda Beach, caused something of a sea-change in Australian society. Prior to these two crimes, parents had no qualms at all about allowing their children to roam around with no adult supervision, and perceived their neighborhoods to be perfectly safe. However, after Jane, Arnna, and Grant vanished without a trace, the previous era of free-range parenting abruptly came to an end.

As the years went by, several possibly related crimes took place in the area, leading police to investigate a handful of suspects they felt might have been responsible for taking the Beaumont children. One of these persons of interest was a man named Bevan Spencer von Einem, who would in 1984 be convicted of the murder of fifteen-year-old Richard Kelvin, and further suspected in a series of brutal killings collectively known as the Family Murders.

Though von Einem appeared to mainly target males in their mid-teens to mid-twenties, investigators began to suspect him of abducting the Beaumont children after a police informant identified only as Mr. B stated that he had heard von Einem bragging that he had kidnapped three children from a beach, had performed surgical-style experiments on them (as he had on his later victims), and then dumped their bodies in some bushland not far from Adelaide.

Von Einem was known to hang around Glenelg Beach, and did look somewhat like the witness descriptions of the man who had been seen with the Beaumont children before their disappearance, though he was at the time only in his early twenties. It should be noted that he would also come up as a suspect in the still-unsolved kidnapping and possible murder of Joanne Ratcliffe and Kirste Gordon, which occurred in 1973.

Another strong suspect was Arthur Stanley Brown, who in 1998 (at the age of eighty-six) was tried for the 1970 rape and murder of young sisters Judith and Susan Mackay in Queensland. Though Brown was never formally convicted, as he was found to be suffering from dementia and therefore unfit to be tried, he was also considered a likely candidate for the man who had kidnapped Joanne Ratcliffe and Kirste Gordon, an abduction that most investigators believe was linked to the vanishing of the Beaumont children. Arthur Brown also resembled the police sketch of the man seen with the Beaumonts, but authorities were unable to place him in the Glenelg beach area at the time of the crime. Brown died in 2002, and the extent of his involvement was never determined.

Less probable suspects included businessman Harry Phipps, who lived very near Glenelg Beach in 1966 and owned a nearby factory where various anomalies were found in the soil after police excavated the area following an anonymous tip. But a more thorough investigation of the site in early 2018 turned up nothing pertaining to the case.

Another man investigated in the disappearance was convicted sex offender Alan Anthony Munro. An associate of Munro’s told police that his children had seen the bodies of the Beaumonts in Munro’s car back in 1966, and there was some evidence placing Munro in the vicinity of Glenelg Beach at around the time of the abduction. However, this particular associate, Allan Macintyre, was also investigated for the crime, though he was cleared, and the information he had was only second-hand.

Also a potential culprit was infamous child killer Derek Percy, whose name had also been bandied about as a possible suspect in the Wanda Beach murders, discussed previously. His conviction in 1969 for the murder of twelve-year-old Yvonne Tuohy was thought to be only the tip of the iceberg, as he was believed to be involved with several other slayings of young children. He was known to be in the area when the Beaumont children disappeared, but at the time, he was only seventeen years old, considerably younger than the man witnesses had described as accompanying Jane, Arnna, and Grant away from the beach.

There was a further development in the case later on in 1966, but it proved to be nothing but a heartbreaking and frustrating distraction. The disappearance of the Beaumont children was not only huge news in Australia, of course, but around the world as well, and by the time November 8th, 1966 rolled around, famous Dutch psychic Gerard Croiset had gotten wind of the crime, and flew to Australia to offer his services.

Not surprisingly, his “visions” were of no help in finding the Beaumonts. At first, he claimed that the children had not been abducted at all, but had accidentally fallen into a drainage pipe. Police did search the area, but were doubtful that the children’s deaths had been accidental, as it seemed unlikely for three children to die accidentally at the same time with neither their bodies nor any of their possessions turning up anywhere.

Next, Croiset changed his story and said that the children had been kidnapped, murdered, and buried beneath a layer of new concrete at a warehouse building site near the Beaumont home. The owner of the warehouse balked at tearing up his new floor on the whim of a psychic, but a hopeful public raised nearly forty-thousand dollars to have the floor pulled up and searched. Nothing was found. The building was thoroughly searched again in 1996, when it was undergoing a partial demolition, but just as before, no trace of the children was discovered.

In 1968, about two years after the disappearance, there was yet another frustrating development in the tragic case. The children’s parents, Jim and Nancy Beaumont, received two letters purportedly written by nine-year-old Jane. In these missives, which bore a postmark from the town of Dandenong in Victoria, the writer referred to a person only identified as “The Man” and claimed that this individual was taking good care of the children and was acting as their temporary guardian.

In one of the letters, “Jane” wrote that the man who was keeping her and her siblings was willing to return them to their parents, and suggested a meeting place where the handover could be made. Police were operating under the assumption that the letters were genuine, as the handwriting and tone of the letters seemed similar to previous writings by Jane Beaumont. A hopeful Jim and Nancy, trailed by a plain-clothes detective, went to the appointed spot at the date and time specified in the letter.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, neither “The Man” nor the abducted children made an appearance. Another letter that arrived shortly afterward stated that the kidnapper had indeed brought the children to the meeting place, but had changed his mind after seeing that the Beaumonts were accompanied by a police officer, and thus were untrustworthy, from his perspective. Jim and Nancy Beaumont received no more letters, and the case went cold once again.

In 1992, authorities were able to extract a set of fingerprints from the letters and determine that they had been a hoax all along, written by a boy who was only fourteen years old in 1966 and was otherwise uninvolved in the case. The writer of the letters, who was forty-one years old when the hoax was discovered, reportedly felt terrible about his teenaged joke, and was never charged with any crime.

The Beaumont children remain missing and presumed dead. As of 2018, there is a $1 million reward on offer for information leading to the conviction of the person or people responsible.

2 thoughts on “The Wanda Beach Murders and the Disappearance of the Beaumont Children”