In the spring of 1984, the finding of a dead infant on an Irish beach would lead to a gross miscarriage of justice and a cultural sea-change in the country concerning women’s rights, a long-standing fight that still continues to the present day.

It was April 14th, and a man jogging along White Strand beach in Cahirsiveen, County Kerry, Republic of Ireland happened upon the remains of a three-day-old baby in the sand. The child had been strangled, and stabbed more than two dozen times.

The Irish police, known commonly as the Gardaí, had no clue as to who the infant belonged to, or who might have murdered him. The ensuing inquiry, which to modern sensibilities seems like something more akin to a medieval witch hunt than a twentieth-century police investigation, saw detectives grilling thousands of women of child-bearing age from across the peninsula, trying to locate someone who might have just given birth, and asking probing questions about boyfriends, adultery, sexual histories, and whether the women knew anyone who had been hiding their pregnancy or had attempted to obtain an illegal abortion at some point in the recent past.

Soon enough, the Gardaí had found a candidate: a twenty-four-year-old woman named Joanne Hayes, who lived on a small farm in Abbeydorney, about fifty miles away from the beach where the murdered infant—dubbed Baby John—had been found.

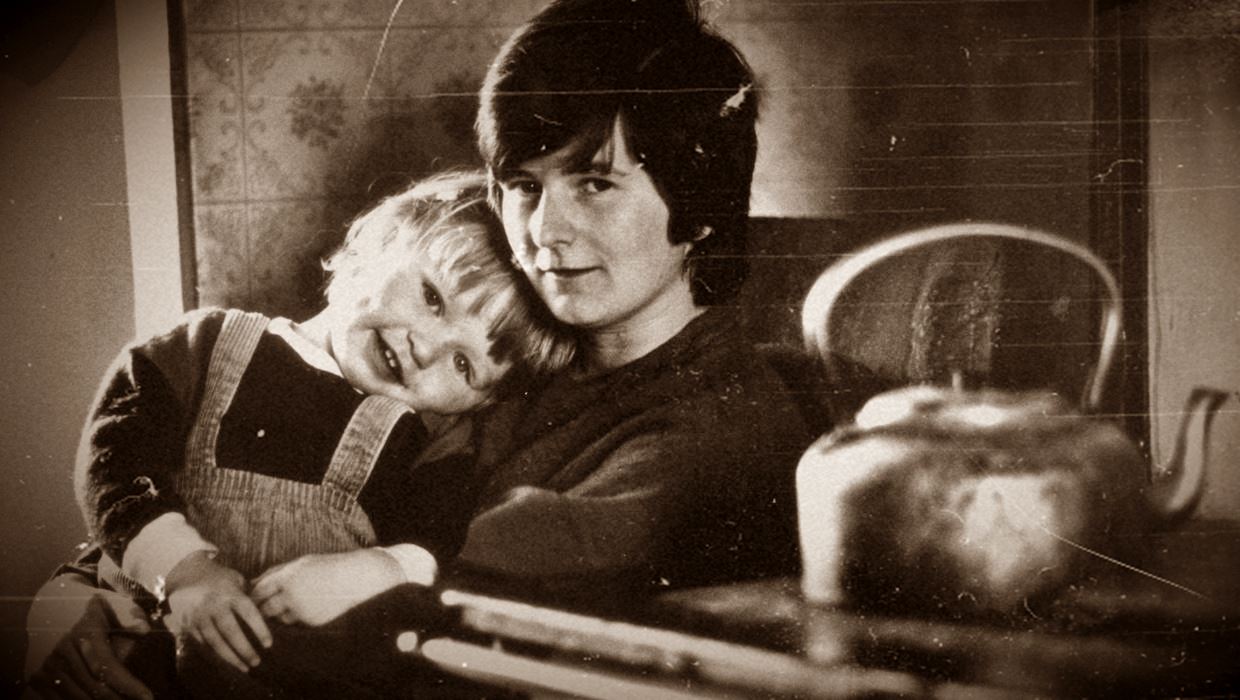

Joanne seemed to tick all the boxes: she had been having an affair with a married man named Jeremiah Locke, which had come to an end a few months before. She had been pregnant and trying to conceal it from family and coworkers. And she had given birth to a child only one day before Baby John’s remains were recovered.

Joanne was brought before the Gardaí and interrogated. The baby she had given birth to, she said, had died shortly after being born, and she had buried him secretly at the family farm. She had developed complications a few days after the birth, however, which had necessitated her visiting a hospital; the Gardaí had seen a record of this when they scoured the medical files of all the facilities in the area. She insisted that Baby John was not her child, and claimed she could prove it, if only they would dig at her family’s farm and find the body of her own infant.

But after hours of alleged strong-arming and possible physical force exerted by the Gardaí, a confused and exhausted Joanne confessed to having killed Baby John. She would later maintain that the Gardaí had threatened her and her daughter Yvonne in order to get her to own up to the crime. In fact, after the interrogation, she rather quickly recanted her confession, charging that it had been coerced out of her.

Joanne was sent to a psychiatric hospital, where she was finally able to convince the authorities to search the farm where she lived. There they found the remains of a newborn infant, exactly where Joanne had claimed they would be, and what’s more, the baby had type O blood, just like Joanne did. The child found on the beach had blood type A.

Though police grudgingly dropped the charges, it didn’t stop them from still attempting to pin Baby John’s murder on the hapless Joanne. They tried to account for the differing blood types by theorizing that Joanne had actually given birth to twins fathered by two different men, via the rare condition of heteropaternal superfecundation. Though this scenario was not impossible, it seemed farfetched, given the circumstances.

Worse still, during the investigation, the authorities had few qualms about assassinating Joanne’s character, exposing her private life to public scrutiny and excoriating her sexual morality. The Ireland of 1984, it must be stressed, was still very much under the patriarchal sway of the Catholic Church: abortion, long since unobtainable in practice, had been officially made illegal the year before. Contraception was only prescribed to married women, and then only sparingly. Even condoms required a prescription for purchase. Irish schools, with church-approved curriculum, did not teach any form of sex education. Even divorce was illegal up until 1996. The stigma surrounding out-of-wedlock births was so profound that it was not unusual at all for girls to die giving birth in hiding, or even going so far as dumping their newborns in rivers or quarries to keep from having to own up to the societal shame of being an unwed mother.

In this cultural atmosphere, then, it was not surprising that Joanne Hayes was vilified, though many Irish women sympathized with her plight and sent her yellow roses in support. The police who questioned Joanne were investigated, but later cleared of all charges that they had physically and psychologically coerced her into a false confession. Thirty-four years after the incident, they formally apologized, and in 2019, reportedly offered a monetary settlement to the Hayes family, though the sum apparently came with some strings attached: Joanne would not be allowed to take any further legal action against the Gardaí, would receive no written apology, and would be forbidden from discussing the case going forward. In addition, the State would admit to no liability in the matter. As of this writing, the Hayes family have not accepted these conditions and are considering legal action.

The murder inquiry into the death of Baby John was reopened in 2018, and the infant’s remains were exhumed in September of 2021, but so far the case has not been resolved.