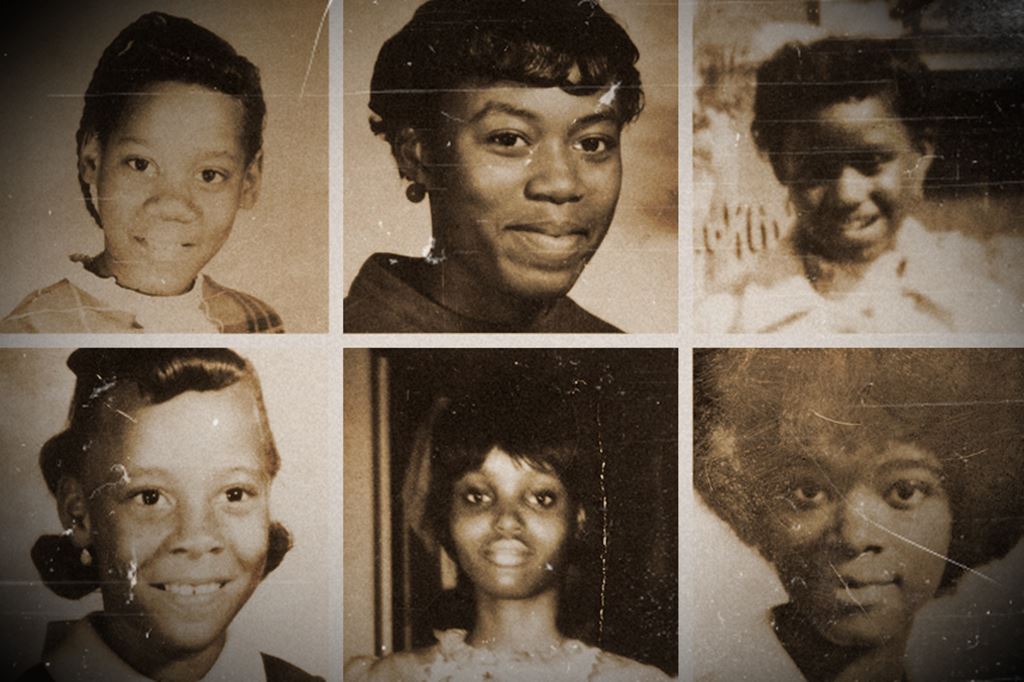

Thirteen-year-old Carol Spinks set out on the evening of April 25th, 1971 to walk to a 7-Eleven store less than half a mile from her home; her older sister had given her five dollars to pick up a few things. On the way to the store, Carol was seen by her mother, who had been in a nearby town visiting a relative and was returning home. Mrs. Spinks, who had told Carol not to leave the house while she was gone, nonetheless allowed the girl to continue on to the store, though she warned her to come straight home afterward or she would be in big trouble.

Carol arrived at the store without incident, and purchased the items her older sister had requested, which included soda, a loaf of bread, and some TV dinners. But on her short walk back home, tragically, Carol Spinks disappeared.

When the child didn’t return from her errand, Mrs. Spinks and Carol’s other siblings fanned out all over the neighborhood, but could find no sign of her. Panicked, Mrs. Spinks phoned the police and reported her daughter missing.

For nearly a week, no trace of the child was discovered, but on Saturday, May 1st, authorities finally found the remains of the thirteen-year-old on an embankment near Suitland Parkway. She had a bloody nose and multiple cuts on her hands, chest, neck, and face. She was still wearing the clothes she had last been seen in, though her shoes were missing and were never found.

Investigators determined that the child had probably been dead for twenty-four to thirty-six hours, meaning that whoever had abducted her had kept her alive for at least a few days prior to killing her, a theory that was supported by the fact that she had eaten citrus fruit shortly before her death, a meal that had presumably been provided by the murderer.

Cause of death was found to be strangulation. Carol Spinks had also been sodomized. Upon closer inspection of her clothing, several synthetic green fibers were recovered, which detectives hoped might lead them to a suspect.

Progress on the case went nowhere over the ensuing days, however, and although the authorities didn’t realize it yet, the coming months would see several more similar homicides that would eventually be laid at the feet of an unidentified killer known only as the Freeway Phantom.

At approximately ten-thirty a.m. on the morning of July 8th, 1971, sixteen-year-old Darlenia Johnson was heading to her summer job at the Oxon Hill Recreation Center, and disappeared at some point along her journey. One witness later told police that they thought they had seen Darlenia getting into an old black car driven by an unidentified African-American man.

On July 19th, eleven days after she vanished, the body of Darlenia Johnson was discovered in almost the exact same spot where Carol Spinks’ remains had been found the previous May. Significantly, Darlenia had lived only a few blocks away from Carol, who was the first child to fall victim to the Freeway Phantom.

Darlenia had seemingly been strangled, though her body was too decomposed to establish either a definite cause of death, or whether she had been sexually assaulted. Sadly, it appears that police inaction was to blame for the delay in finding her body; a week prior to her remains being recovered by detectives, a motorist who was having car trouble stopped on the side of I-295 and spotted the body, at which point he naturally phoned police.

However, authorities evidently just drove by the scene and didn’t investigate any further, reporting back to the station that nothing had been amiss. After a week had gone by, the same motorist mentioned to his boss that he had heard nothing about the girl being found, and the boss took it to a friend of his, who happened to be a police sergeant. Upon returning to the site, the sergeant found that the body was still there, and had substantially deteriorated after spending a week in the summer heat. This perceived lack of effort on the part of investigators led some in the community to feel that the murders were being given short shrift because the victims were black, a sentiment which still echoes up to the present day.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the killer of these two young girls would strike again only weeks later.

On July 27th, 1971, ten-year-old Brenda Crockett walked to the store a few blocks away from her home after her mother told her to pick up a few items the family needed, including bread and dog food. An hour later, the child had not returned.

The Crocketts’ searched the neighborhood for the girl, but could find no sign, and after returning home, reported Brenda missing. Three hours after Brenda vanished, however, the phone rang. Brenda’s seven-year-old sister Bertha answered the call. It was Brenda, and it sounded as though she was crying.

Brenda told her younger sister that she had been picked up by a white man, and that she thought she was in Virginia. She also claimed that she was in a cab and was heading home. Brenda then abruptly said goodbye and hung up.

Bertha told her mother and her mother’s boyfriend what Brenda had said, and no sooner had she finished relaying the information than the phone rang again. Mrs. Crockett’s boyfriend answered.

Brenda was again on the other end of the line. She repeated that she thought she was in Virginia and that a white man had picked her up. She then said that she was in a house alone with this man.

Mrs. Crockett’s boyfriend asked Brenda to put the man on the phone so he could find out where Brenda was. Strangely, Brenda then asked, “Did my mother see me?” The boyfriend asked her how her mother could see her if she was in Virginia. There then came the sound of heavy footsteps approaching the phone on Brenda’s end. The child quickly said, “I’ll see you,” and the call was disconnected.

These eerie phone calls would be the last time the Crocketts’ spoke to Brenda.

Several hours later, a hitchhiker came across the body of Brenda Crockett, which had been dumped in a conspicuous area off Route 50 near Interstate 295. She had been raped, and strangled with a scarf that was still knotted around her neck. Just as in the case of Carol Spinks, Brenda had synthetic green fibers on her clothing.

Police at the time hypothesized that Brenda’s killer had forced the child to make the phone calls to her family, in order to throw the authorities off his scent. Other than this supposition, however, investigators had little else to go on, and the identity of the Freeway Phantom remained as inscrutable as ever.

Then came October 1st, 1971, and just as in the case of Carol Spinks and Brenda Crockett, twelve-year-old Nenomoshia Yates had been sent on an errand to pick up some groceries. She was last seen purchasing her items in a Safeway store near her home, but sometime after leaving the store, she disappeared.

Hours later, her raped and strangled body was found in Prince George’s County, Maryland, right alongside Pennsylvania Avenue. She also had green synthetic fibers on her clothes, just as two of the previous victims had.

Following the death of Nenomoshia Yates, the media coined the Freeway Phantom name, a moniker by which the unidentified serial killer is still referred.

More than a month later, the murderer would claim his final victim of 1971, and leave a bone-chilling calling card.

On the evening of November 15th, 1971, eighteen-year-old Brenda Woodard was having dinner at the home of a school friend in Washington, D.C. After the meal, Brenda got on a bus that would take her back to her home on Maryland Avenue. Once she got off the bus, she fell into the clutches of the Freeway Phantom.

Approximately six hours after she was last seen, Brenda’s remains were discovered near the Route 202 access ramp off the Baltimore-Washington Parkway. Like the previous four victims, Brenda had been raped and strangled, though unlike the others, she had also been stabbed four times, and was found with her velvet coat draped over her chest.

The most horrifying clue recovered from her body was a handwritten note that the killer had placed in her pocket. It read, “This is tantamount to my insensititivity [sic] to people especially women. I will admit the others when you catch me if you can! Free-way Phantom.”

The note was written on a piece of paper that had been ripped out of Brenda’s notebook, and the handwriting appeared to be Brenda’s, suggesting that the killer had dictated the note to his victim. Because the note did not appear to have been written under duress—in other words, since the handwriting looked exactly the same as other samples of Brenda’s writing—police speculated that Brenda perhaps knew the killer and had initially had no reason to fear him.

Despite this latest troubling clue, however, the Freeway Phantom would evidently not kill again until nearly a year later.

It was the evening of September 5th, 1972, and seventeen-year-old Ballou High School student Diane Williams made some dinner for her family before taking a bus to her boyfriend’s house for a short visit. Later that night, her boyfriend walked her to the bus stop and watched her board the bus for the return journey home. She never made it there.

Only a few short hours later, on the early morning of September 6th, a truck driver who had pulled over to the side of I-295 to take a rest found the young woman’s body. Like the other victims of the Phantom, Diane had been raped and strangled, and green fibers were found on her clothing.

Despite the general feeling in the community that authorities were not placing a priority on solving the murders, investigators did interrogate and process hundreds of suspects and persons of interest, though all their efforts would ultimately prove fruitless. They did, however, establish a handful of very strong possibilities.

The prime suspect in the murders, at least according to D.C. police detective Lloyd Davis, was a man named Robert Askins. Askins had been convicted in 1938 of poisoning a prostitute in Washington D.C., though he had only served twenty years before being released on a technicality.

Detective Davis found it odd that Askins was known to use the word “tantamount,” which had appeared on the note found in the pocket of victim Brenda Woodard. A search of Askins’ home, furthermore, produced photos of women and girls, as well as a few dirty women’s scarves. Investigators also discovered a gold earring and a few buttons in Askins’ car; significantly, fifth victim Brenda Woodard had been found with some buttons missing from her skirt and coat.

Though the circumstantial evidence seemed promising, forensic tests on the green fibers found on the clothing of five of the victims established that the fibers did not match any fibers in either the home or the vehicle of Robert Askins, and his hair likewise did not match hair found at the crime scenes. Though he was cleared of the Freeway Phantom killings, however, he was later convicted of kidnapping and raping two women in D.C., and spent the rest of his life in prison, dying in 2010.

Another later series of suspects put forward by investigators involved a gang of rapists known as the Green Vega gang, because of the vehicle they were often spotted in, a green Chevy Vega. Two of the men associated with this gang had been convicted of rape and murder in D.C. at around the same time as the Freeway Phantom murders were going on, and the gang was thought to comprise at least three other men.

One of the two members of the gang who was serving time at Virginia’s Lorton Prison told police that another member of the Green Vega group had been responsible for the murders attributed to the Freeway Phantom. Though some detectives were convinced the inmate was telling the truth, others felt that he was only feeding them details about the crimes that he had read in the papers, and didn’t have any particular insight into the killer at all. And just as in the case of Robert Askins, hair samples taken from all the men in the Green Vega gang failed to produce a match with hairs found at the Freeway Phantom scenes.

In 1974, two ex-cops from Washington D.C., Edward Sullivan and Tommie Simmons, were arrested for the murder of fourteen-year-old Angela Barnes, who was initially suspected to be a victim of the Freeway Phantom. After authorities determined that her killing was not connected to the others in the series, they resumed looking into other suspects.

Some investigators have attempted to generate a psychological profile of the suspected killer, who they believe was a black man in his twenties or thirties at the time of the murders, an individual with above-average intelligence and a job, who probably lived in the same neighborhood as the first two victims, but later hunted prey farther afield in order to escape detection. Some researchers into the case also speculate that he might have been a veteran suffering from PTSD, or someone with a particular hatred for police.

Though much of the original evidence in the murders has been lost or has deteriorated due to poor preservation, the case remains open, and surviving family members of the six victims are still hoping for some resolution.

As of 2022, there remains a $150,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the unknown serial killer.