It was the early morning of Monday, June 20th, 1994. Twenty-two-year-old David Bain, a student at Otago University in Dunedin who had been studying classical music and singing, set out on his part-time paper route, ostensibly leaving the rest of his family sleeping at home.

According to his later account, David arrived back at the Every Street residence at around six-forty-five a.m. and entered the house quietly, without turning on any lights. He went into a downstairs bathroom to wash the newspaper ink off his hands, and while down there, he also put a load of clothes into the washing machine, including an olive green sweater whose significance would be hotly debated at the later murder trial.

Once the laundry was going, David went to his room and there noticed a few bullets and the trigger lock from his .22 caliber rifle lying on the floor. He wasn’t initially alarmed at seeing this, but after turning on the lights in the house and making his way upstairs, he soon discovered that his entire family had been brutally massacred.

Fifty-year-old Margaret Bain, David’s mother, was sitting upright in her bed. She had been shot in the face. David’s sisters, nineteen-year-old Arawa and eighteen-year-old Laniet, had both been shot in their beds, presumably while they slept. His fourteen-year-old brother Stephen was dead in his room; he appeared to have been the only victim who had put up a fight against the killer, for he had been partially strangled before being shot, and fibers were found beneath his fingernails. Lastly, David’s fifty-eight-year-old father Robin was prone on the floor of the lounge, the rifle lying beside him, blood and brain matter spattered all about.

Eerily, someone had typed a message on the computer in the lounge where Robin’s body was found. It read, “Sorry, you are the only one who deserves to stay.” A shocked David Bain phoned police at nine minutes past seven a.m., telling authorities, “They’re all dead.”

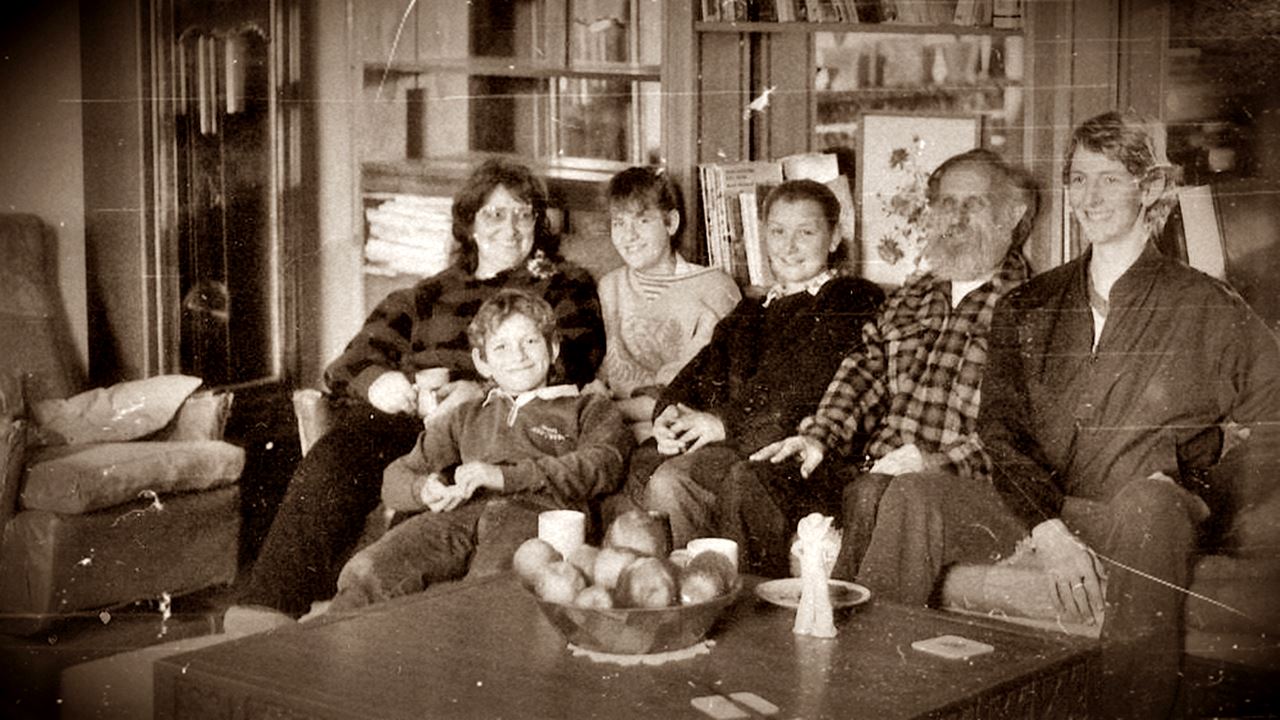

During the initial stages of the investigation, it was suspected that Robin Bain had actually killed the family and then turned the gun on himself after David had left on his paper route that day. The family dynamic of the Bains, it should be noted, was somewhat bizarre. They were stringently religious, and also appeared to have hoarding tendencies. Robin and Margaret were essentially estranged; Robin, in fact, lived at the school he taught at during the week, and when he was home on the weekends, he slept in a filthy trailer in the backyard.

Even more to the point, daughter Laniet, who lived elsewhere and reportedly worked as a prostitute, told at least four separate people that Robin had been molesting her for years, and indeed, she had supposedly come home on that particular weekend for the specific purpose of telling the family what had been going on.

However, only a few days after the multiple murder, son David Bain was arrested and charged with the crime. Authorities believed that he had a motive for killing his family: namely, the substantial sum of money they had set aside in order to build a new house to replace the derelict one they were living in, a sum that would now go directly to David.

The police put forth a scenario whereby David had shot his mother and siblings before going out on his paper route, then after he returned, had waited in the house for his father Robin to come in from the trailer for his daily prayers and had then shot him as well. He then purportedly typed the cryptic message on the computer to make the whole scene look like a murder-suicide.

Investigators further pointed out that the rifle used to perpetrate the slayings unquestionably belonged to David, though the ammunition and the key to the trigger lock were apparently kept in David’s room, and Robin also had easy access to them; in fact, some later evidence suggested that Robin had used David’s rifle before.

Another point of contention was the green sweater that David had thrown into the washing machine before allegedly finding the bodies of his family. Fibers from this sweater were found beneath the fingernails of fourteen-year-old Stephen Bain, all but confirming the fact that Stephen had struggled with the attacker. The sweater actually belonged to Robin, and when David was asked to try it on at the ensuing trial, it appeared too small for him, though the prosecution argued that David had put on weight during his stint in jail.

Also at issue was an unaccounted-for twenty-five minutes between the time David arrived back at his family home and the time he phoned the police for help. On the stand, David simply explained that he was in shock upon finding the bodies of his parents and siblings, and spent some time going from room to room to check if any of them were still alive. This would also account for the fact, said the defense, that there were smears of blood from several of his family members on the back lower hem of David’s t-shirt and the crotch of his black shorts.

A few other confusing clues muddied the waters of the investigation. For instance, the left lens off a pair of glasses ostensibly worn by David were found in Stephen’s room, and the prosecution maintained that the lens had popped out during the death struggle between Stephen and David. The glasses actually belonged to David’s mother Margaret, but David had been wearing them off and on; the frame and right lens were discovered in his bedroom. However, other sources assert that the lens was found beneath an ice skate and covered with dust, suggesting it had been lost a significant amount of time before the murders.

A pair of white gloves that supposedly belonged to David was likewise found in Stephen’s room, with the fourteen-year-old’s blood smeared on them. It is unknown whether David or Robin was wearing the gloves; the only fingerprints found on the rifle were Stephen’s, as he had obviously grabbed the barrel of the firearm during the struggle.

On the other hand, some evidence that seemed to point more in the direction of Robin Bain’s guilt was considered inadmissible and not presented at the trial, including the supposition that Robin had been molesting his daughter and that she had been planning to confront the family about it. Also not mentioned was the fact that Robin had been suffering from a profound depression, had been neglecting his personal hygiene, had been recently reprimanded at work for striking a student, and had published some strange and violent stories in the school newspaper, one of which involved a character who murdered his entire family.

Ultimately, David Bain was found guilty of the five murders and sentenced to life in prison in 1995. However, former rugby player and businessman Joe Karam believed that David was innocent, and took it upon himself to get the case retried. David was released on bail in 2007 pending the outcome, and in 2009, David was found not guilty, and released after serving thirteen years in prison. In 2011, David attempted to get compensation from the New Zealand government for wrongful imprisonment, a claim that was initially rejected by the Minister of Justice. But in 2015, a second review of the case was undertaken, and though this review concluded that David Bain was probably not innocent of the crimes he was accused of, he was ultimately awarded a one-time ex-gratia payment of $925,000 New Zealand dollars and told to consider the matter settled.

The Bain family murders remain a controversial topic in New Zealand, and opinion seems neatly divided between those who believe David killed his family and those who believe Robin committed the crime before turning the rifle on himself. Undoubtedly, both men had motive, means, and opportunity, but the evidence seems ambiguous on either score. David Bain later changed his name, married a schoolteacher, had a son and moved to Australia with his new family, but doubts about his guilt still remain, and the case has been a source of fascination for more than twenty years, spawning several books, podcasts, a 2010 stage play, and a 2020 TV series titled Black Hands.