In June of 1984, a young woman would disappear from a Stockholm street and later turn up butchered, in a crime that would eventually go on to become Sweden’s most notorious unsolved murder and the inspiration for Stieg Larsson’s internationally best-selling book, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.

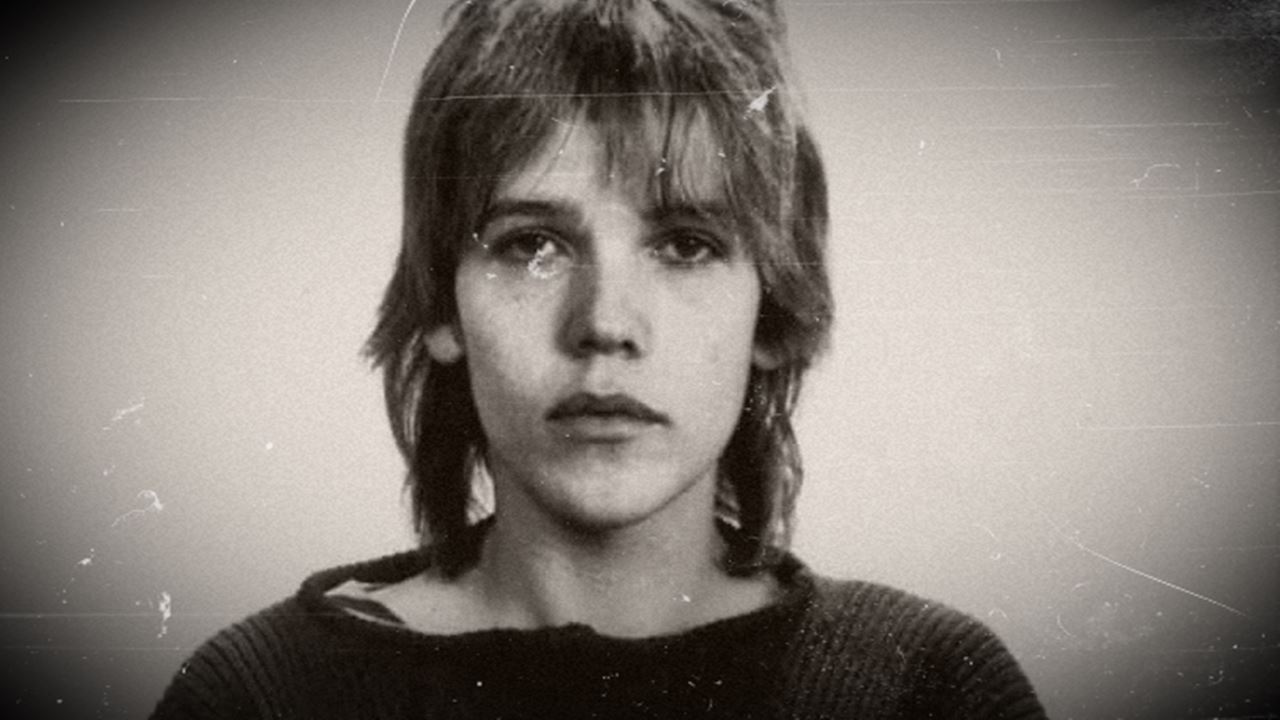

Twenty-eight-year-old Catrine da Costa, a prostitute and heroin addict, was a regular fixture on the Malmskillnadsgatan, the short stretch of road in the Stockholm city center where sex workers plied their trade. Catrine had been married once before and had a son, but had fallen on hard times.

On June 10th, 1984, she was seen getting out of a man’s car, but thereafter seemed to vanish without a trace. Catrine’s mother, who had maintained a very close relationship with her, became extremely concerned when she didn’t hear from her daughter, and reported the disappearance to police.

There was no sign of her until July 18th, when pieces of her dismembered corpse were discovered in a garbage bag beneath an overpass in Solna, just north of the city center. More parts were recovered a few weeks later, though her head, internal organs, genitalia, and one breast remain missing. Though the victim was identified as Catrine da Costa through her fingerprints, a cause of death was never able to be determined.

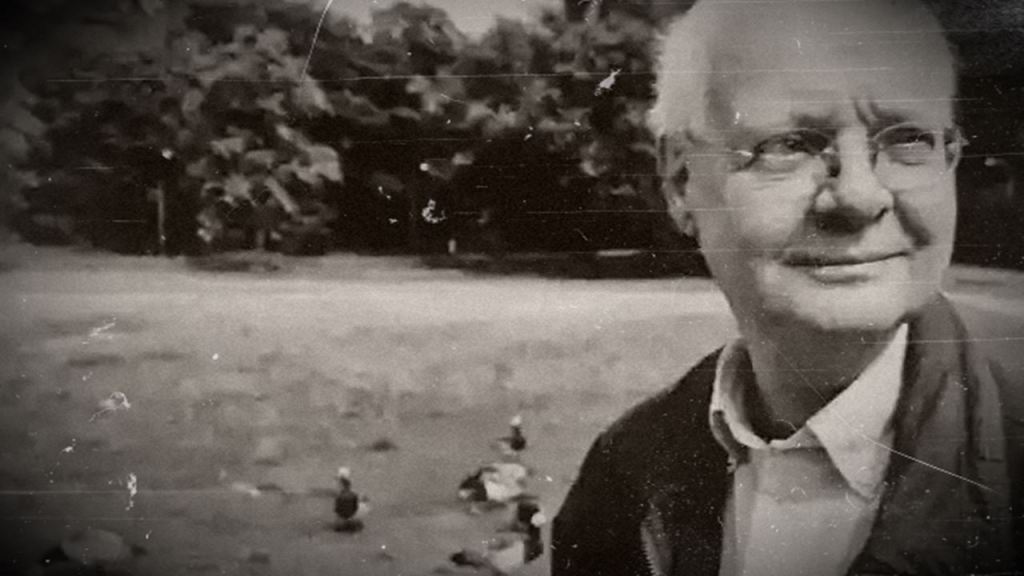

Shortly after the body was found, a pathologist named Teet Härm came to the attention of investigating authorities. Härm was known to frequent prostitutes, and worked at a forensics lab at the Karolinska Institutet, a location almost exactly halfway between the sites where the two sets of body parts were found.

Not only that, but in 1982, Härm’s wife Ann-Catherine was found hanging in the couple’s home. Though the coroner ruled her death a suicide, police suspected Härm may have killed her, particularly because she had filed for divorce shortly before she died, and Härm had reacted with odd detachment to her passing. It was Ann-Catherine’s father, in fact, who alerted detectives to consider Härm as a person of interest.

Further, rather eerily, the pathologist specialized professionally in cases of strangulation, and had written several papers on the subject, as well as aided the authorities in other homicide investigations where the victims had been strangled. Notably, a former supervisor of Härm’s named Jovan Rajs was convinced that Härm was the killer, and stated as much to investigating officers.

A survey of the prostitutes of the Malmskillnadsgatan produced fifty positive identifications of Härm, and one woman even claimed that he had beaten her up during their encounter. A search of Härm’s home turned up knives and violent pornography as well; the doctor was then arrested for the murder of Catrine da Costa.

Meanwhile, as all of the investigation surrounding Härm went on, another individual was also appearing on the police’s radar. This was a former colleague of Härm’s, a general practitioner by the name of Thomas Allgén. Not long after Catrine da Costa’s remains were recovered, Allgén’s wife Christina was in the process of divorcing him, on the grounds that he had sexually abused their two-year-old daughter. Though this claim was never conclusively proven, Christina would soon insist that the child made statements indicating that she had witnessed a woman being cut apart by her father and another man who looked like Härm. As Allgén and Härm were known to be acquainted, Allgén was subsequently arrested also.

Arguments presented at the trial of the two men included all of the aforementioned circumstantial evidence, as well as the statements of two owners of a photography shop in Stockholm who claimed that they had developed a set of photos in the summer of 1984 that appeared to depict a body cut into pieces; these photos were subsequently picked up, they said, by a pair of men matching the descriptions of Härm and Allgén.

The doctors were initially convicted of murder in the case, though due to a technicality concerning unauthorized interviews with the media given by some of the jurors, the verdict was soon overturned. A public outcry ensued, and Härm and Allgén were later put back on trial.

At this second hearing, the men were acquitted of murder, especially as Catrine’s cause of death had never been conclusively established, though the judge stated that he believed Härm and Allgén were at least guilty of cutting up Catrine’s corpse. However, as desecration of a body was not a major offense and held a very brief statute of limitations, the suspects were released.

The verdict caused a massive controversy in Sweden which has never really been satisfactorily resolved. Though the doctors were deemed not guilty of the murder, a large portion of the public were of the opinion that they had gotten away with a horrific crime, and various campaigns by members of the press and others were later able to get both doctors’ licenses to practice revoked.

Härm attempted suicide in 1985, and in later years, both he and Allgén tried to sue the state for defamation, and to recover the loss of income that had been incurred by their suspected involvement in the murder. To date, none of their legal actions have been successful, and it remains unknown whether they were, in fact, guilty of killing Catrine da Costa.

Interestingly, there was another suspect who was initially believed to be very promising, though police eventually dismissed him for reasons which are still a bit murky. Polish butcher Stanislaw Gonerka had been in a mental institution since 1974, after having been convicted of strangling and dismembering a woman whose body parts were later found discarded in several garbage bags. Gonerka had only been released from the hospital three months before Catrine was murdered, and was also recognized as a regular among the prostitutes of the Malmskillnadsgatan; he was thought, in fact, to have purchased Catrine’s services specifically, as his name was found written in her diary.

Gonerka died in 1987, and though forensic evidence was obtained from his body in order to try to match it with physical evidence recovered from Catrine’s remains, no definitive link could be made, and the case is still unsolved.