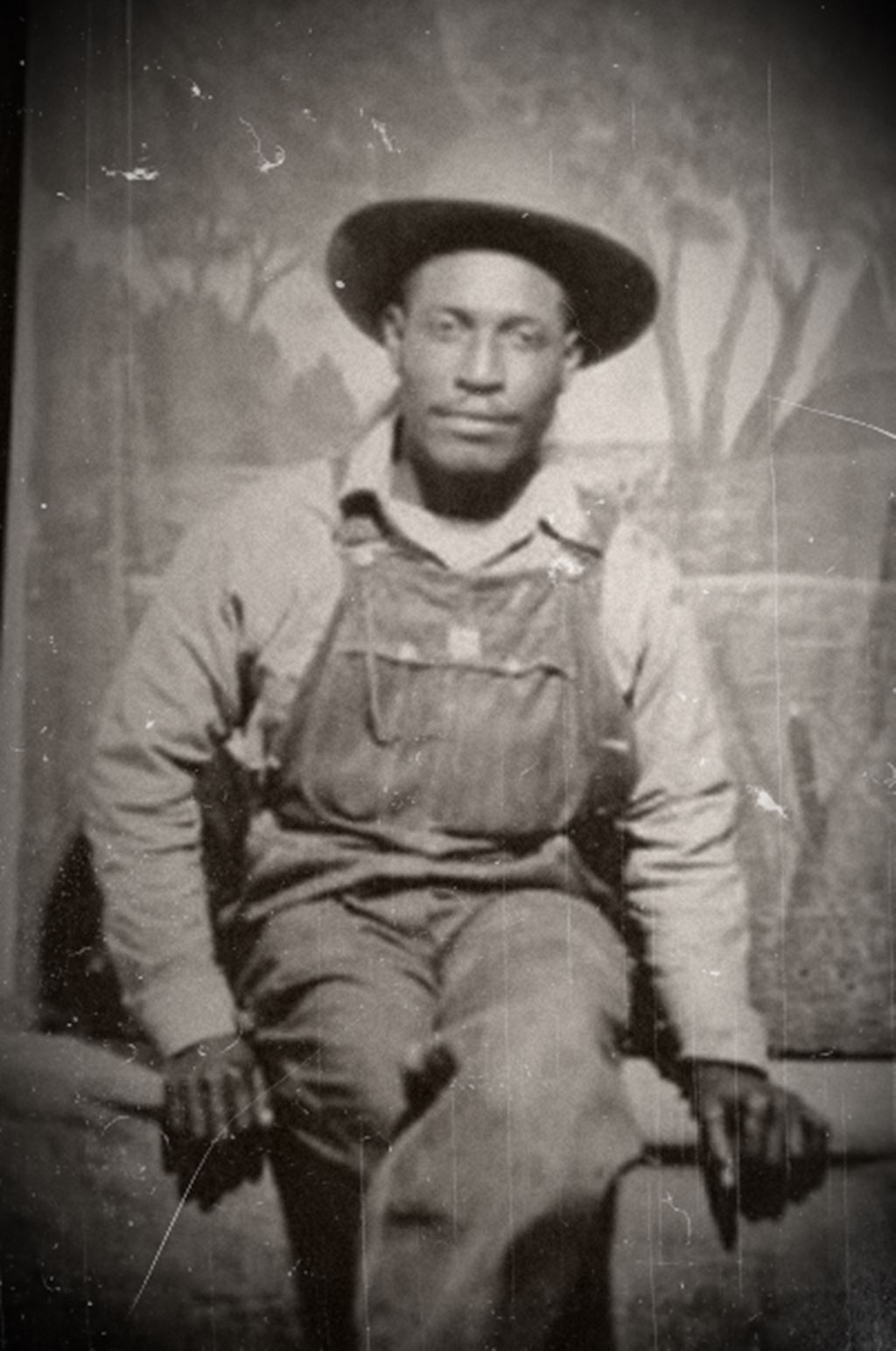

Louis Allen was a native of Liberty, Mississippi, where he had lived all his life, save for a stint in the Army during World War II. He had worked as a farmhand and a logger, and was eventually able to save enough money to purchase his own land, from which he ran a small logging business, as well as raising cattle and various other crops. He and his wife Elizabeth had four children.

Beneath this thin veneer of success, however, Louis Allen and his fellow African-Americans in Mississippi were very much second-class citizens. They were not allowed to vote, and were routinely harassed—and sometimes beaten and killed—by the very law enforcement officers who were supposed to be protecting them, many of whom were also members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Louis’ particular troubles began back in September of 1961, when he happened to be walking past the Westbrook Cotton Gin and witnessed a state representative, E.H. Hurst, shooting and killing voting rights activist and NAACP member Herbert Lee. Several civil rights activists had been in Liberty over the summer of 1961, attempting to register blacks to vote, as they had been disenfranchised in the state since 1890. Many of the white citizens of Mississippi were not taking kindly to this “intrusion.”

There was an inquest the day after Lee’s murder, at which Louis Allen and the eleven other witnesses were present, but a contingent of armed and threatening white men at the inquest essentially cowed the witnesses into testifying that Hurst had killed Lee in self-defense. Hurst was exonerated.

The fact that Louis had been intimidated into lying didn’t sit very well with him, though. He was, by all accounts, an extremely honorable and proud man who had no compunctions about standing up for himself. At last, he decided that he was going to tell the FBI the truth about the murder. Before he did so, he discussed his decision with Julian Bond, a voting rights activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee who would go on to become one of the best-known leaders of the civil rights movement. Bond encouraged Louis Allen’s actions, but understood that once word got out about what he had done, Louis would no longer be safe.

Louis traveled to Jackson, Mississippi to speak with the FBI, offering to tell them what really happened if they would promise to protect him. The FBI seemed well aware that Louis’ life would be in danger if he testified truthfully, and in fact even noted in 1961 that there was already a rumored plot to kill him that involved the local sheriff and as many as seven other conspirators. Despite this, they stated that they would not be able to guarantee his safety. Louis, therefore, simply repeated the “self-defense” lie, making sure that the FBI knew that he would change his testimony if they offered him protection.

Although Louis Allen had not told federal agents the truth, the fact that he was willing to do so caused a great deal of consternation among the governing authorities in Liberty. A campaign of harassment against Louis began: he started mysteriously losing customers of his logging business; other businesses in town refused to serve him; he and two other black men were shot at while attempting to register to vote; and he was verbally threatened to keep his mouth shut on numerous occasions.

Even worse, Louis was repeatedly arrested on false charges, such as weapons violations, and in September of 1962, he was assaulted by Amite County Sheriff Daniel Jones, who hit Louis in the face with a flashlight, breaking his jaw. Jones was the sheriff that the FBI memo had been referring to, and indeed it does seem that the bulk of the harassment leveled at Louis Allen prior to his murder was directly or indirectly engineered by Jones. Though Jones declined to comment on whether he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan, it is known for certain that his father was a high-ranking member of the Klan’s Liberty chapter.

Once Louis was released from jail following the jaw-breaking incident, he filed a complaint against Sheriff Jones, but it was summarily dismissed by an all-white jury. In early 1963, a friend and employee of Louis’ named Leo McKnight was killed, along with his entire family, in a house fire that is suspected to have been deliberately set. And later that year, Louis Allen was arrested again, this time on false charges that included bouncing a check and carrying a concealed weapon, for which authorities were threatening to lock him away for three to five years. He was bailed out by the NAACP.

At this point, Louis had more than enough of his little hometown. He had only been staying there during all the trouble because he was taking care of his elderly mother, but after she died in January of 1964, he began making preparations to move. He was planning to go to Milwaukee on February 1st to stay with his brother, but unfortunately, he wouldn’t leave Liberty, Mississippi alive.

On the evening of January 31st, Louis was driving onto his property in his truck. He stopped the vehicle so that he could get out and open the cattle gate that marked the beginning of the driveway. As he opened the gate, he was ambushed by an unknown assailant or assailants and shot two times in the head with a rifle. He died instantly. His son Hank found the body sometime later, partially hidden beneath the truck.

The investigation into Louis Allen’s death, if it could be called an investigation at all, was by all accounts laughably inadequate. No physical evidence was gathered at the scene, and it does not seem that any suspects were sought or interviewed. Sheriff Jones essentially shrugged his shoulders at the press, telling them that he hadn’t been able to come up with a single clue. But Hank Allen, Louis’ son, stated that Sheriff Jones had bluntly told him and his mother Elizabeth that if Louis had kept quiet, he would still be alive.

In fact, it appears that the murder was swept completely under the rug until 1994, when a historian at Tulane University, Plater Robinson, became interested in the case and decided to investigate it himself. He pored through existing records and interviewed witnesses in Liberty who were still alive and willing to talk to him. Through Robinson’s efforts, it came to light that Sheriff Daniel Jones was indeed the most likely gunman. According to sources, Jones had been accompanied on the night of the shooting by a black man named Archie Weatherspoon, who Jones had brought along to be the trigger man. When Weatherspoon balked at shooting Louis, the sheriff then allegedly did it himself.

Though Daniel Jones does seem a solid suspect, it should be noted that he has repeatedly denied killing Louis Allen, and that no known physical evidence exists linking him to the crime. The FBI reopened the case in 2007 as part of their renewed effort to solve cold cases from the civil rights era, but as of this writing, the killer of Louis Allen in Liberty, Mississippi remains unknown.

One thought on “Louis Allen”