In the very early spring of 1966, a terrifyingly random murder of a little girl on a New Jersey street in the middle of a sunny afternoon would mark the beginning of a formerly safe town’s tragic downward spiral.

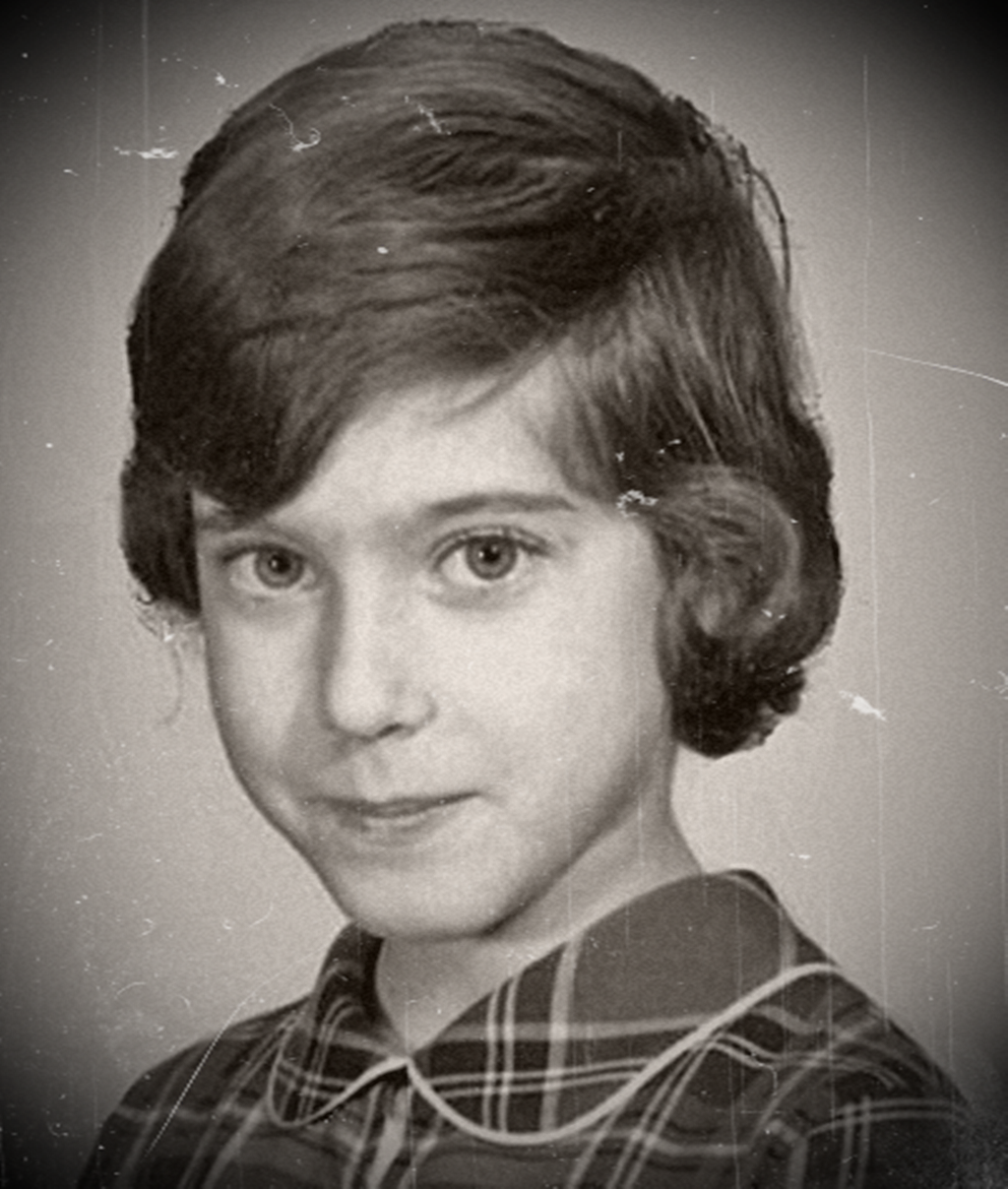

It was about four p.m. on March 8th, and seven-year-old Wendy Sue Wolin was standing on the sidewalk outside of her upscale apartment building on Irvington Avenue in Elizabeth, New Jersey, waiting for her mother to bring the car around from the parking lot. The mother and daughter were planning to do some shopping before picking Wendy’s older sister Jodi up from school.

As the child strolled along the sidewalk, a tall, muscular, middle-aged man clad in a dark green corduroy coat and a gray fedora walked past her, crouching down a little so that he was nearly eye level with the girl. He then punched her in the stomach, or so she thought, and then he kept on moving as though nothing had happened.

Wendy doubled over, prompting several passersby to ask her what was wrong. Wendy told them that a man had just punched her, and with their help, she made her way to the nearby fire station, where police were called.

She told police and firefighters that she had been hit in the stomach, but she appeared calm and in no pain, giving her name and address with no trouble. However, when officers opened her coat to have a look at her wound, they saw that the little girl had actually been stabbed, and was bleeding profusely.

Believing that an ambulance would not respond quickly enough, the police immediately drove the child to Elizabeth General Hospital, but by the time they arrived, there was nothing to be done for her. Wendy Wolin died at five-fifteen p.m., less than an hour after the attack. The single stab wound, from a hunting knife, had pierced her liver and her right lung, and had also chipped two of her ribs.

The knife was found in its sheath the following day, in the gutter near where Wendy had been stabbed. A delivery truck had parked on top of it before police had sealed off the area.

The ensuing manhunt was one of the largest in New Jersey’s history. Authorities turned over every stone, searching buses, trains, and outgoing ships; setting up traffic blockades; and interviewing thousands of witnesses. A composite sketch of the likely perpetrator was produced, and as the investigation continued, numerous—and ominous—sightings of the man from the same day were reported by multiple individuals.

A man fitting the description of Wendy’s attacker had apparently stabbed an eleven-year-old girl in the buttocks earlier that afternoon, and had assaulted several other teenaged girls in the area prior to the stabbing of Wendy Wolin. One of these other victims, twelve-year-old Diane DeNicola, had been punched in the face about half an hour before the attack on Wendy, and though two men had chased the assailant for some distance, he ultimately was able to elude them.

A bus driver in the area also told police that a man matching the killer’s description had pounded on the doors of his out-of-service bus at about twenty minutes past four p.m., and that he appeared to be “on Cloud 9.”

Despite the killer’s crazed recklessness, however, no trace of him was ever discovered, and no arrests were ever made.

The case was reopened in 1995, and a few tantalizing new pieces of information came to light, including the fact that a Highland Park neighbor of Anne and Mae Rubenstein, the victims of a double homicide from 1965, insisted that she had seen the same man who was suspected of killing Wendy Wolin near the Rubenstein home on the day they were murdered. The mother and daughter, incidentally, had been viciously slaughtered in their home in broad daylight on February 13th, 1965, with a kitchen knife. Neither Anne nor her eleven-year-old daughter Mae had been sexually assaulted, and nothing had been stolen from the home, leaving authorities baffled as to the motive for the gruesome killings.

There was, in fact, a strange coincidence that seemed to tie the crimes together. It turned out that Wendy Wolin and her family had moved to Elizabeth only about two weeks after the murder of Anne and Mae Rubenstein. Prior to that, the Wolin girls had lived with their grandparents, whose last name was also Rubenstein, though the families were evidently not related. The grandparents’ home was only a block away from the house where Anne and Mae had been murdered.

Jodi Wolin later reported that she thought her grandfather had owed money to the mob, and that perhaps the slaying of Anne and Mae Rubenstein had actually been a case of mistaken identity. She went on to assert that perhaps Wendy Wolin was later killed when the mob realized its mistake and belatedly took revenge on the granddaughter of their initial target.

Despite many theories circulating about the connection, however, investigators have not been able to establish a link between the two cases.

A more promising lead in the 1995 reexamination came in the form of a woman who had been attending a wake in Elizabeth when she spotted a man who she said had molested her as a child. She suddenly realized that this man bore an uncanny resemblance to the composite sketch of Wendy Wolin’s killer, a sketch which everyone who had grown up in the city was intimately familiar with.

The police asked the man, who has never been publicly named, to come in for questioning, and he willingly complied. At the time of the slaying, the man had lived ten miles away from where the crime took place, but admitted that he was originally from Elizabeth. He also conceded that he owned and would have worn a gray fedora and a dark green coat in 1966. The man also had a history of mental illness, and notably, had called in sick to work on the day that Wendy Wolin was killed.

From his relatives, investigators were able to procure a photograph of the man that had been taken in 1966, and they placed the photo in a lineup that they showed to five witnesses from the day of Wendy’s murder. Three of the witnesses were absolutely sure that it was the same man, while the other two were not certain.

The suspect was interrogated intensely and given two polygraph tests, both of which he passed. He continued to maintain his innocence, and without a confession, there was little police could do to keep the man in custody, since the remainder of their evidence against him largely consisted of witness testimony of an event that had taken place three decades earlier. He was eventually released, and died in 1998 with no further charges being brought against him.

The case of Wendy Wolin still burns in the memory of everyone who grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and has since been identified as the harbinger of the city’s downfall, from the previously safe and quiet multi-immigrant community of the mid-twentieth century to its current status as the city with one of the highest average crime rates in the United States.

One thought on “Wendy Wolin”