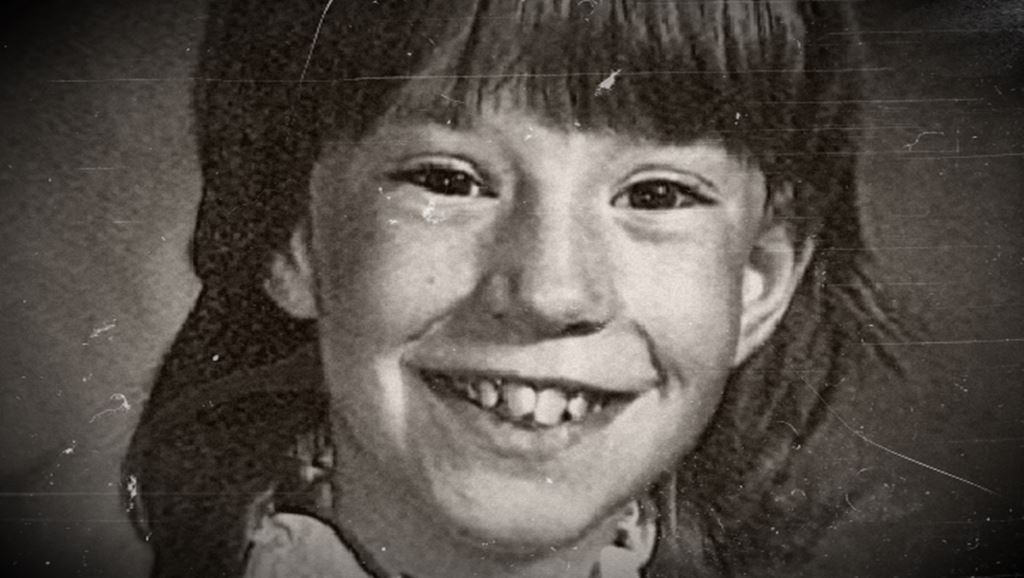

It was October 3rd, 1984, and nine-year-old Christine Jessop hopped off the school bus at around three-thirty p.m. Neither her parents nor her brother Kenney was home; her father was still at work, and her mother had taken Kenney to the dentist. They expected to be home at four, and Christine’s mother had told the girl to wait in the house for them to get back.

Christine, though, apparently had other plans. She and her friend Leslie Chipman had agreed to meet up at nearby Queensville Park with their dolls at four, and before setting out, Christine picked up her family’s mail, left it on the kitchen table along with her school book bag, then walked to a convenience store on the corner to buy some gum. She was seen there between three-forty-five and three-fifty p.m. by both the proprietor of the store, and by a customer named Robert Atkinson, who told police she had been in the shop holding her recorder.

Leslie went to the park as planned, but Christine never showed up to meet her. Concerned, Leslie went back home and phoned the Jessop house at around ten minutes past four, but got no answer. She called again at four-twenty, and this time Christine’s brother Kenney answered, having just arrived home from the dentist. But Christine wasn’t there.

Family and friends fanned out across the neighborhood, but found no sign of her, at which point they reported her disappearance to police. The authorities likewise had no luck in locating the child, though after questioning residents of the area, they thought they might have a suspect in the abduction: a twenty-three-year-old neighbor named Guy Paul Morin.

According to witnesses, Morin was a strange, reclusive young man who kept bees and played in a band. Though he had a girlfriend and a steady job, neighbors thought it odd that he never went to pubs, as most other young men his age did, and detectives’ alarm bells were set off by his stoic behavior under interrogation. Further, a police dog tasked with searching Morin’s car apparently indicated to handlers that Christine had been in the vehicle.

Though questioning of Morin continued, the case stagnated for the following three months, until a grim find forced the proceedings from a missing persons inquiry to a homicide investigation.

On the last day of 1984, the decomposed body of nine-year-old Christine Jessop, last seen at a convenience store near her home in Queensville, Ontario, Canada, was found in a wooded area approximately thirty miles from her last known location. She had been raped and stabbed multiple times. Semen was recovered from the child’s underwear, but as DNA testing was still very much in its infancy in 1984, police could do nothing but store the evidence and hope that better technology would soon be able to confirm the identity of the killer.

In the meantime, though, investigators were fairly convinced that Guy Paul Morin was the most likely suspect, despite him having a solid alibi for the time of the homicide, and they arrested him a few months after Christine’s remains were recovered. At his trial, a forensic technician claimed that red fibers found in Morin’s car had come from Christine’s sweater; further circumstantial evidence was given by two inmates at the jail where Morin had been held, who told the assembled jurors that Morin had confessed the murder to them.

Morin was actually acquitted at the first trial, the judge citing lack of compelling evidence, but the Crown appealed the verdict, and Morin stood trial again in 1992, at which point he was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison.

That wasn’t the end of the story, however. Three years later, in 1995, a DNA test was performed on the pair of Christine’s underwear that had been recovered from the scene, and the profile of the killer did not match Guy Paul Morin. He was released after spending approximately eighteen months in Kingston Penitentiary and eventually won more than a million dollar settlement from the government of Ontario for his wrongful conviction.

But if Guy Paul Morin did not kill Christine Jessop, then who did? The question remained open for years. Other suspects were notably difficult to come by, though in 2018 a private investigator named Jay Nicoll told the press that he was looking into a man called Richard Stanley James, who was arrested less than a month after Christine’s disappearance for abducting a six-year-old girl named Lynn Ferguson from the parking lot of a convenience store. The little girl was thankfully not harmed, as James’s truck broke down and he let his victim go, but it seems significant that James appeared to be driving toward the town of Sonya, not far from where Christine’s body ultimately turned up. Lynn Ferguson also told police that the kidnapper had lured her into his vehicle by telling her he had lost his puppy and would give her two dollars to help him look for it.

In 2020, however, the murder of Christine Jessop was at long last definitively solved as a result of diligent investigative work and a DNA genealogy lab, which built a familial lineage from the killer’s preserved sample taken in 1984. In October of 2020, authorities announced that the suspect was a man known to the family, a neighbor named Calvin Hoover, who was twenty-eight years old at the time of the crime.

In 1984, Hoover’s wife worked with Christine Jessop’s father, and Christine and her brother would often play with the Hoover children, though Kenney Jessop told the media that though he remembered Hoover’s wife, he didn’t particularly remember Calvin, the man who allegedly murdered his sister.

The family had been hoping for some closure in the form of justice, and perhaps a chance to confront Christine’s suspected killer, but this was unfortunately not to be, as Calvin Hoover had died by his own hand in 2015. Despite this, the Jessop family, as well as the wrongfully convicted Guy Paul Morin, have expressed relief and gratitude at the long-sought-after resolution of the case, with Kenney Jessop in particular calling the solving of the murder “an absolute miracle.”