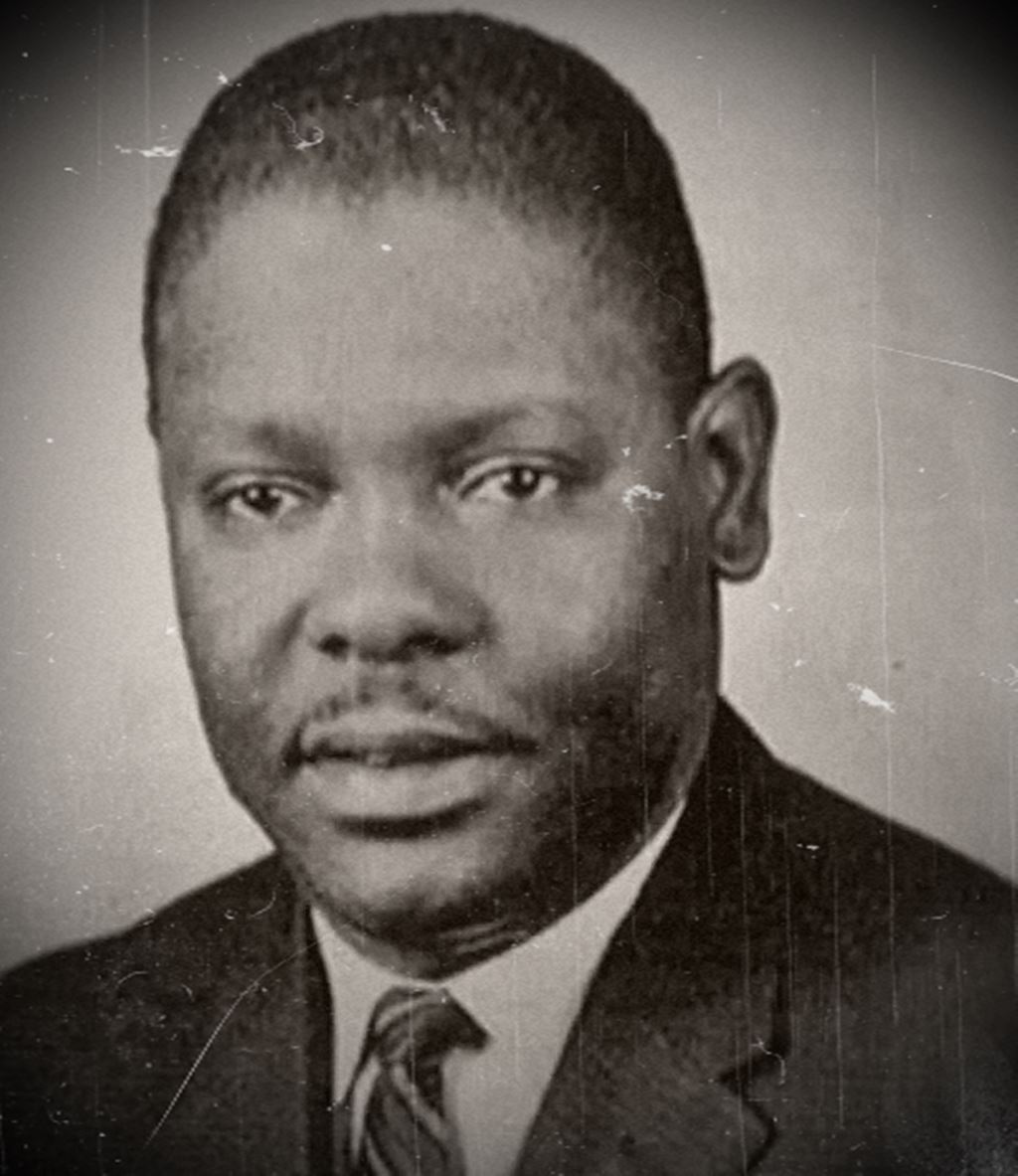

Thirty-eight-year-old Edwin T. Pratt was a prominent figure in the black community in Seattle. He had been born in Miami, and had had a distinguished career as an activist for the Urban League in various cities before settling in the Seattle area in 1956 and eventually becoming the Executive Director of the Urban League chapter there. Edwin was heavily involved in the fight for public school desegregation, as well as advocating for equal opportunities in housing and employment for black citizens.

Given the heightened racial tensions in the United States all during the era, Edwin was unsurprisingly a polarizing individual among certain sectors of the population. More militant black activists accused him of being too moderate and too willing to compromise on rights issues, while the white supremacist crowd just wanted him to shut up and go away. Edwin received numerous death threats on a daily basis, and according to some sources, was justifiably beginning to become somewhat paranoid.

In fact, by the end of January 1969, he was evidently at a crossroads in both his personal and professional life, and was ready for a change. He had reportedly been having an affair with his white secretary for quite some time, and had finally mustered up the courage to ask his wife Bettye for a divorce. By some accounts, Bettye, with whom Edwin had two young children, had not taken the news very well, and had threatened to kill him if he left, though she later claimed she hadn’t really meant it.

Career-wise, Edwin was also apparently planning to leave activism behind, having become worn down by the constant harassment. He had, in fact, been considering moving away and taking a job in the corporate sector, perhaps working for Boeing, a company at which he had a few connections.

Whatever Edwin Pratt’s visions for the future were, though, he would not live to see them realized.

On the evening of January 26th, Edwin was at his home in Shoreline, Washington, which he still shared with Bettye. According to a statement by Edwin’s secretary and alleged mistress, who has declined to be named in the press, she and Edwin had planned a dinner date for that Sunday night, but Edwin cancelled after an unusually heavy snowfall had made driving the streets a hassle.

It was a little past nine p.m., and Bettye had just put the children to bed when both she and Edwin heard what she later described as the sound of a snowball hitting the side of the house. Bettye peered out the bedroom window, while Edwin, who had been in the living room, opened the front door to see what the noise had been.

From her vantage point, Bettye could see the figures of two men hunched behind Edwin’s car, which was parked in the driveway. To her horror, she realized that one of the men was holding a rifle that was aimed straight at her husband. She screamed to him that they had a gun, but by that time, it was too late. There was a muzzle flash, and Edwin Pratt fell dead on his front doorstep, shot directly in the face with a 12 gauge shotgun. The perpetrators then took off running across the snow and jumped into a car, which quickly sped off into the night.

Due to the blanket of darkness, no one who witnessed the shooting was able to tell police whether the killers were white or black, though from the way they ran, they both appeared to be in their late teens or early twenties, and both stood about six feet tall. Investigators believed that aside from the shooter and his accomplice, there had also been a third man involved, who had driven the getaway car. Again, the darkness of the evening made identifying the vehicle difficult, though one witness came forward and stated that he thought it had been a two-toned, newer model Buick Skylark.

It seemed as though the weather was a complicating factor as well, as police were unable to procure a clear tire track or set of footprints from the sloppy, melting snow, and though a shell casing was recovered from the scene, it was too common a brand to be of any use in narrowing down a suspect. Additionally, it appeared that not a great deal of care was taken in securing the crime scene itself, for reportedly hundreds of police officers, firefighters, and civilians were allowed to roam around the Pratt house and yard over the course of the night.

Two days after the murder, the mayor announced a public day of mourning, and a reward of over ten thousand dollars was offered for any information leading to the arrest of the assailants. The FBI was also brought in to aid in the investigation, since the motive for the murder appeared to be related to Edwin’s civil rights activities. Despite the crime’s high profile and the amount of money on offer, however, the case remained frustratingly nebulous, with very few leads and far too many people who had reason to want Edwin Pratt dead.

The slaying remained on the back burner until 1995, when several people, including Edwin’s daughter Miriam, petitioned to have the original case files released to the public in the hopes that someone with information would come forward and finally lay the crime to rest. The petition was only partly successful, however, and among the files not released were transcripts of interviews with potential suspects.

That same year, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer conducted their own investigation into Edwin Pratt’s killing, and discovered that even back in 1969, investigators had had their eye on one man in particular: twenty-one-year-old Tommy Kirk.

Kirk was a drug dealer and addict, as well as a petty criminal, and it turned out that there was a very good reason why police had never been able to build a case against him: only about three months after the murder of Edwin Pratt, Tommy Kirk was himself found murdered. The man convicted of killing him, in fact, was Texas Barton Gray, who was later suspected of being the second man seen crouching behind Edwin Pratt’s car on the night of the murder.

This information apparently came from a former associate of Kirk’s, Steve Butler, who further alleged that not only had Tommy Kirk and Texas Barton Gray been responsible for Edwin’s death, but that they had actually been paid between ten thousand and twenty-five thousand dollars to assassinate him. By the time this story came out, however, Texas Barton Gray was also dead, having succumbed to a heart attack in 1991.

The murder inquiry was reinvigorated once again in 2011, when Seattle Weekly was finally granted access to some of the case files previously withheld from the public. These seemed to confirm that Tommy Kirk was indeed the prime suspect for the gunman, while Texas Barton Gray was pegged as his accomplice. The man who had driven the getaway car was thought to be another small-time hood, twenty-two-year-old Michael Lee Jordan, who indeed owned a two-toned, yellow and black Buick at the time of the murder.

The case files also appear to suggest that many investigators believed the three white men had been contracted to kill Edwin Pratt by a black man, Henry Roney, an outspoken local builder with alleged ties to the Black Panthers and a particular disdain for Pratt, who he perceived as an Uncle Tom. According to this scenario, Roney was believed to be acquainted with Tommy Kirk through the Panthers, to whom Kirk sometimes sold drugs.

Roney, who died in 1996, vehemently denied involvement in the plot, insisting that though he had no respect for Edwin Pratt as a person, he had no reason at all to want him killed. And those with close ties to the Black Panther movement during the period in question deny that Roney was connected with them in any capacity, and further allege that the Panthers had absolutely no beef with Pratt, regardless.

Another of the FBI’s possible suspects for the money man in the theoretical scheme was black activist and teacher, Keve Bray, a rival of Henry Roney’s who had been accused of inciting violence through some of his writings in the journal he published, and was also a suspect in a car bombing that targeted the then mayor of Seattle. Bray himself was murdered in Denver in 1972 by Daniel Karlem, apparently for reasons that were largely personal rather than political.

While few people involved with investigating the case seem to have much doubt about the identities of the three actual assailants, however, the murder-for-hire angle is still very much under debate. According to Danella Jordan, who was the wife of alleged getaway car driver Michael Lee Jordan at the time of the slaying, there was no contract hit out on Edwin Pratt and no money was ever exchanged. She asserts that the shooting was a straightforward hate crime, perpetrated by virulent racist Tommy Kirk.

Danella told investigators that Kirk had made no secret of his wish to kill a rich black man, and chose Edwin Pratt in particular because of his high profile in the media, as well as the fact that Pratt’s family lived in a well-to-do, all-white neighborhood. Michael Lee Jordan himself, talking to investigators in 1995 from the prison where he was serving time for robbery, seemed to corroborate his ex-wife’s story, stating that Kirk had killed Pratt for no more complicated reason than blinding racial hatred.

Though most of the evidence does seem to point to Tommy Kirk as the gunman, there was another white man investigated for the crime who also seemingly had a racial motive: an ex-convict by the name of Kenneth Moen. People acquainted with Moen claimed that he had threatened to kill Pratt on more than one occasion, and after the murder had allegedly confessed it to several witnesses who later came forward. His motive appeared to be along the same lines as Kirk’s, getting some measure of revenge against a successful black man.

Additionally, Moen was known to own a shotgun, had formerly been convicted of several armed robberies, and was staying in a house very near to the Pratt family home in Shoreline. He allegedly told friends that he shouldn’t have worn shoes with pointed toes during the commission of the crime, and the investigation did find that at least one of the assailants had worn similar shoes.

In spite of this circumstantial evidence, though, a polygraph test appeared to show that Moen was not involved in the murder of Edwin Pratt, and as Moen died in 2005, his involvement will likely never be proven one way or the other.

In their 2011 summary of the case, Seattle Weekly wrote that the case had been all but solved, and that Tommy Kirk was most definitely the man who pulled the trigger, though whether he had been a hired gun or merely a murderous racist is unknown. Since all of the main suspects have subsequently passed away, and since so little physical evidence from the original crime scene remains, the case is still considered officially unsolved.