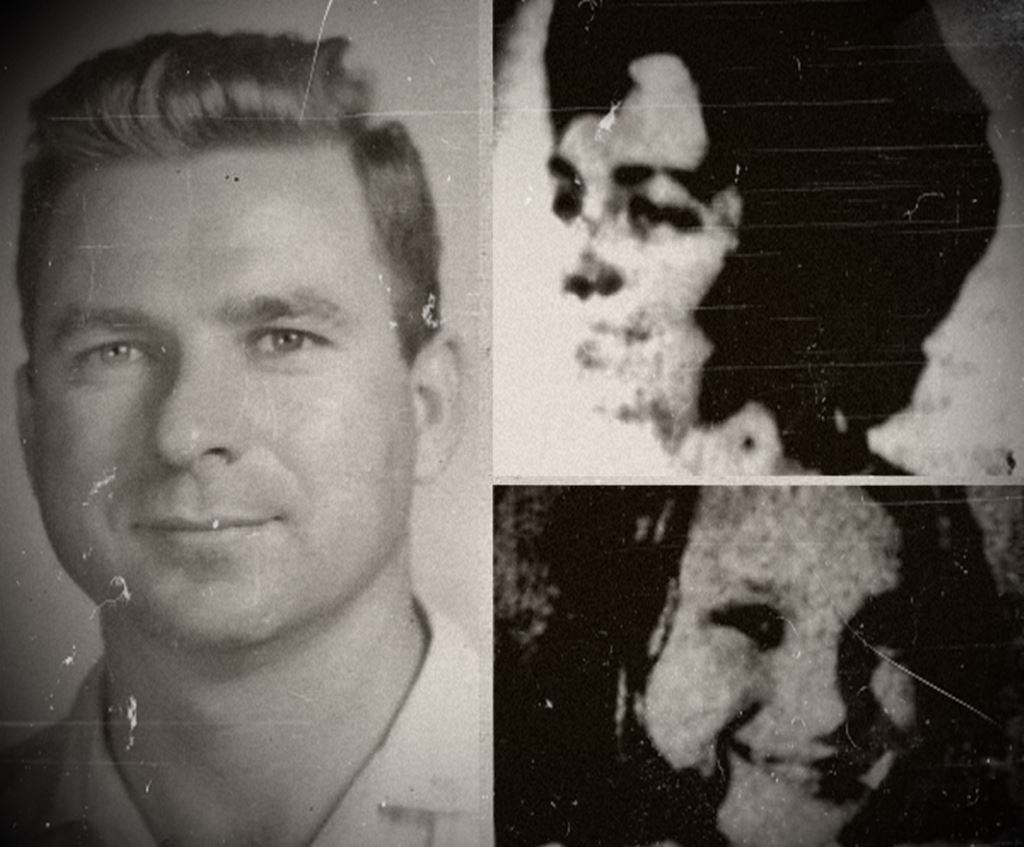

The Sims family had recently moved to Tallahassee, Florida from their former home in Meridian, Mississippi, and were already a beloved and well-respected clan in their middle-class neighborhood. Forty-two-year-old Dr. Robert Sims was the Director of Data Processing for the Florida Department of Education, and his thirty-four-year-old wife Helen served as church secretary and pianist at the First Baptist Church in Tallahassee. The couple had three daughters: seventeen-year-old Jenny, sixteen-year-old Judy, and twelve-year-old Joy.

It was Saturday, October 22nd, 1966, and Tallahassee was packed to the gills with attendees of the North Florida Fair, as well as football fans watching the Florida State Seminoles playing the Mississippi State Bulldogs. As evening fell, Robert and Helen Sims were sitting at home with their daughter Joy, listening to the radio. The two older daughters were out baby-sitting for neighbors that had gone to the stadium for the football game.

Jenny Sims arrived home from her baby-sitting job first, at a quarter past eleven p.m. As she entered the family home at 641 Muriel Court Drive, she thought it strange that neither her parents nor her sister was anywhere to be seen. With trepidation, she crept down the hall, peering into all the rooms and calling out for her family. When she looked into the master bedroom, she recoiled in horror.

Her father Robert Sims lay across the bed, bound and blindfolded, an enormous pool of blood staining the bedspread beneath him. He had been shot once through the head. On the floor, Helen Sims lay at an angle near the bed, also bound, blindfolded, and covered in blood. She had been shot twice in the head and once in the leg. Twelve-year-old Joy lay beside her mother, clad in her nightgown. She had been tied up, shot once in the head, and stabbed six times in the chest.

Though contemporary reports of the slaying indicate no evidence of sexual assault, later accounts confirm that Joy’s underwear had been pulled down, and that she bore unspecified signs of having been molested.

As Tallahassee at the time had no emergency services, the terrified Jenny phoned Bevins Funeral Home, which also served as the ambulance depot. When Russell Bevins and his sixteen-year-old son Rocky arrived at the scene, they discovered that Robert and Helen were still clinging to life, though Joy had sadly been killed outright. Robert died only moments after the Bevinses reached him, but Helen was transported to the nearest hospital, where she languished in a coma for nine days, after which she also passed away.

Larry Campbell was the first police officer to arrive at the Sims’ home, and although he would later receive a great deal of criticism for his failure to properly secure the crime scene—in essence allowing hundreds of unauthorized persons to walk through the house and possibly contaminate the evidence—it should be noted that this rather lackadaisical approach to forensics was not unusual for the time, and was further exacerbated by Tallahassee officials’ lack of experience with a crime of this magnitude.

Investigators discovered no sign of forced entry, and it was clear that robbery had not been the motive, for sums of money and other valuable items remained in plain sight around the house. There also did not appear to be any indication of a struggle; it seemed that the killer had herded the Sims’ into the master bedroom where he proceeded to bind and murder them, suggesting that perhaps the assailant was known to the family.

Authorities immediately undertook a massive inquiry, which was hampered somewhat by the fact that so many strangers had been in town for both the North Florida Fair and the FSU football game. Interviews with the Sims’ neighbors produced little useful information, other than a witness’ claim to have heard something that sounded like a scream at approximately ten-forty-five p.m.

Much as in the case of the Bricca family massacre in Cincinnati, the murder of the Sims family paralyzed Tallahassee with fear, and all across the city, sales of firearms, locks, and guard dogs were brisk. Children were even discouraged from going trick-or-treating that Halloween, or at least confining their activities to daylight hours.

While detectives slowly worked their way through tenuous lead after tenuous lead—at one stage even going so far as to pull library records to pinpoint individuals who had recently checked out a copy of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood—rumors about the likely culprit had begun to swirl around the neighborhood.

The first potential suspect to feature in the local gossip was Cecil Albert Roberts, known as C.A., who was the pastor of the First Baptist Church where Helen had worked as a secretary.

Both townsfolk and law enforcement found it significant that Helen Sims had quit her job at the church only days before the murder, and it was an open secret in the area that Pastor Roberts was a notorious womanizer. Though some believed that the pastor had been carrying on an affair with Helen Sims that went sour, most of the town scuttlebutt leaned more toward the idea that Helen had either rejected him, or was threatening to spill what she knew about his personal affairs.

Luckily for Pastor Roberts, he had an airtight alibi for the time of the murders: he was the team pastor for the FSU football team, and had been at the stadium the entire evening. Close scrutiny of the videotape of the game clearly showed him at the sidelines, and though his presence was unaccounted for during halftime, it was later established that he would not have had sufficient time to drive all the way to the Sims home, murder the family, and then return to the stadium by the second half, when he again appeared on the videotape.

Pastor Roberts was dismissed as a suspect, but the rumors surrounding him nonetheless ruined his career, and he was later forced to resign his post and leave town.

As the investigation and the years wore on, a few other persons of interest periodically drew the attention of authorities. In 1978, a man named Thomas Fulghum was arrested in Atlanta, Georgia for killing and dismembering his girlfriend, Dale Pirnie. When he was taken into custody, police discovered the woman’s liver in a glass jar sitting next to him.

Fulghum claimed he had committed the crime because he was possessed by the Devil. The bizarre nature of the slaying prompted detectives to realize that in 1966, Fulghum had been fifteen years old and had lived only two blocks south of the Sims family in Tallahassee.

Interviews with residents who had known the young man in 1966 indicated that he had seemed completely normal at the time, and it later came to light that his mental problems had not begun to develop until after he served time in the Navy. At any rate, he was soon cleared of suspicion in the Sims murder, as not only had multiple witnesses seen him at a party in Atlanta on the night of the crime, but his fingerprints did not match any of the prints recovered from the Sims crime scene.

Later on, in the early 1980s, a woman named Peggy Howells came forward and pointed the finger of blame at her ex-husband Robert. Peggy stated that the day after their wedding, Robert had confessed to her, in alarming detail, about his involvement in the murder of the Sims’. She also claimed that his motive had been simple anger at Helen Sims after a seemingly insubstantial argument at a grocery store on the afternoon before the killings.

Peggy went on to assert that she had since divorced Robert, and that he was an abusive drunk who had threatened to kill both her and her stepson. Police took her testimony seriously enough that they fitted Peggy with a wire and had her go undercover in an attempt to get Robert to admit to the murders.

The scheme was ultimately unsuccessful, however, as Robert was tipped off about the wire by his daughter. As detectives looked further into the accusations, moreover, it began to become clear that Peggy was simply trying to put her violent ex-husband behind bars by any means necessary; for example, she told police officers that Robert owned a .32 pistol, which she categorized as the murder weapon, when in reality the murder weapon was a .38. Furthermore, Robert Howells not only easily passed a polygraph, but his fingerprints likewise did not match any of those taken from the Sims’ home. He was ultimately dismissed.

There were, however, two more suspects who seemed far more promising. They were both considered persons of interest shortly after the crime occurred in 1966, but the major revelations about them didn’t fully come to light until 1987. Some more conspiracy-minded researchers have suggested that one of the suspects was not properly investigated at the time because his father was a prominent criminal psychologist in the United States and a respected professor at nearby FSU.

Vernon Fox, Jr. and Mary Charles Lejoie—who preferred to be called Charlie—were teenagers who both lived within a few blocks of the Sims family at the time of the killings; indeed, the Fox house was almost directly behind the home of the Sims’. Vernon and Charlie had met in elementary school and became closer over the years, until they eventually began dating as teens.

The pair was seen as a little strange around the neighborhood; Charlie in particular was from a broken home and was known to be obsessed with death and funerary practices. She had actually broken into the Bevins Funeral Home on at least one occasion in order to steal burial shrouds, and Russell Bevins had personally warned her to stay away from his place of business.

On the night of the triple homicide at the Sims’ house, Vernon claimed that he and Charlie had gone to the drive-in to see Dr. Who and the Daleks, and had only stayed for the first few minutes of the second film, Munster, Go Home. He then said they had driven to a secluded location and had sex in the car, after which Charlie had driven him back to their neighborhood and dropped him off a block or two from his house at around seven minutes past eleven p.m.

In a 1966 statement, Vernon also told police that as he had been walking along Gibbs Street toward his house, he had seen a black car which pulled up beside him. One of the two men in the car, Vernon stated, then opened the back door of the vehicle as if inviting him inside, but then the other man was allegedly heard to say, “No, that’s not him.” The car then supposedly drove away. Vernon asserted that he had then continued on his way, gone into his house, made a sandwich, and then retired to his bedroom to watch a Saturday night movie.

The story that Vernon Fox told police, in which he seemed to be trying to imply that the individuals in the car were perhaps hit men who had killed the Sims family and had mistakenly thought that he was one of them, was contradicted not only by neighbors and by Charlie Lajoie, but also by later statements given by Vernon himself.

For instance, though he said he had been dropped off at a little past eleven and had gone into his house, a neighbor named Mrs. Lamb said she had seen Vernon out in the street when the ambulance arrived at the Sims’ house at eleven-twenty-three, and that he was making “strange hand gestures.”

Charlie told police that she and Vernon had actually stayed at the drive-in for two movies, leaving at the beginning of the third; it should be noted, however, that the ticket taker at the drive-in actually corroborated Vernon’s statement, asserting that the pair had indeed left after the first movie.

Charlie also stated that she had not had sex with Vernon in the car after leaving the movies, and in fact did not have sex with him at all until 1967. She also told police that she had dropped him off earlier than he claimed, since she knew she had been home by five minutes past eleven, when she took her birth control pill.

Perhaps more ominously, Vernon Fox was linked to a handful of prowler reports that occurred around the neighborhood prior to the murders, and in fact was allegedly seen peeking into the window of twelve-year-old murder victim Joy Sims on October 15th, about a week before she was killed.

Vernon denied all these charges, and also made the dubious claim that he had lost a knife much like the one used to kill the Sims’ in the pond near their house; this had occurred, he said, many years prior to the murders. Police in fact did drain the pond shortly after the slaying to look for the murder weapons, but nothing was found.

Despite the contradictions and irregularities in the stories told by Vernon Fox and Charlie Lajoie, there was no solid physical evidence tying either one of them to the murders, and they were ultimately dismissed as suspects. They later went on to marry, though they divorced in 1986.

But then, in 1987, Charlie came forward and led the investigation off in a rather strange direction. Allowing herself to be interviewed by police for at least six hours, Charlie went off on a rambling discussion about how Vernon Fox had been sexually attracted to Joy Sims, and how Charlie herself had become fearful that this attraction was going to lead to him getting into trouble.

Investigators began to suspect that perhaps Charlie had committed the murders herself out of jealousy; that she had been present in the house when Vernon committed the crime; or that they had murdered the family together in some sort of twisted pact.

During the course of the conversation with detectives, Charlie made several odd and offensive comments about how “ugly” the Sims girls were, and later came tantalizingly close to admitting her involvement, making statements such as, “Vernon killed the parents…you think I killed the parents? What if I did go in there? What would y’all do to me?”

Additionally, she also seemed to be suspiciously familiar with the layout of the Sims’ house, despite her earlier assertions that she had never been in there. Charlie was further found to have missed her classes at Madison College on the Monday following the murders.

Larry Campbell, who was present during the interview, perhaps unwisely hinted to Charlie that if she was involved in the crime, she would likely be sent to a mental hospital, after which Charlie stopped talking. Other researchers who have looked into the case felt that Charlie was perhaps trying to suss out the police to see how much they knew, as she was savvy enough to avoid saying anything that would directly incriminate her.

Vernon Fox, for his part, denied every one of Charlie’s 1987 allegations, claiming that although he still loved her, he feared for his life because of her tendency toward mental illness and physical violence. After their divorce in 1986, he stated, he had given her their house and their car, both of which were completely paid off, and even gave her a sum of money equal to a year’s worth of alimony payments. The fact that she had tried and failed to get the alimony payments extended, he claimed, was the reason that she had suddenly gone to the police and implicated him in the murders.

Vernon further alleged that he never had any sexual interest in Joy Sims, and that in fact he was generally attracted to older women, not young girls. He also denied ever stalking anyone in the neighborhood or peeking into anyone’s windows, and continued to maintain that he saw two men in a car on the night of the crime who he believed were the actual killers.

Though Vernon’s version of events has changed somewhat over the years, with details generally becoming more concrete but also contradictory over the course of three rounds of statements given in 1966, 1989, and 2016, he is adamant that he is not the killer, and that he never even set foot in the Sims home while the family lived there.

In 2016, in fact, he made a few headlines due to his extensive comments on various blog posts about the Sims murder case, in which he gave detailed accounts of the night of the crime and calmly argued his innocence with other commenters. In one of these comments, he stated that he willingly gave a DNA sample to police, though this has not been confirmed.

The Tallahassee triple homicide is still an open case, and interest in the crime remains high. In October of 2016, director Kyle Jones released a documentary about the Sims murders entitled 641 Muriel Court that features interviews with investigators, neighbors, and witnesses, as well as a talk with Vernon Fox himself. The film also includes segments of the infamous police interviews with Charlie Lajoie Fox, in which she seems to dance around her own involvement in the slayings without admitting anything outright.

Authorities are still holding out hope that the murders of Robert, Helen, and Joy Sims will eventually be solved, though more controversy arose in 2016 when Assistant Leon County State Attorney Jeremy Mutz was fired from his position. It was speculated that his termination was due to his claim that enough evidence existed to arrest a suspect in the crime. Leon County State Attorney Willie Meggs would not comment on the firing or the state of the investigation.

The triple homicide remains unsolved.

There is no evidence that I ever had a .38 pistol. There is no evidence that I had a double edged dagger. There is no evidence that i was a peeping tom. There is no evidence that I was in the Sims house. There is no evidence that I had anything to do with the murders. All this is because I had nothing to do with the Sims or their murders. That is why I was never arrested or charged with anything in connection with the murders. I am innocent in both the legal and moral meaning of innocent. I am a victim of speculation and rumors. I am an innocent victim of false information repeated be people speculating based on fictional stories. I could not kill anyone for any reason. I believe in “Thou shall not kill.”

Vernon B Fox Jr