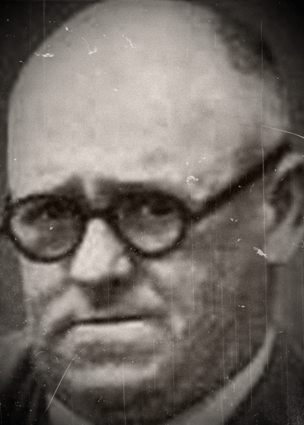

Fifty-six-year-old William “Bill” Murfitt had built a reputation as a hard-driving, modernizing farmer with a lively social life. He and his family had leased Quays Farm in Risby, Suffolk, England earlier in the decade and were well known in the Bury St. Edmunds area.

On the morning of May 17th, 1938, Bill collapsed and died at Quays Farm. A post-mortem was performed, which revealed the cause of death to be cyanide poisoning.

It was determined that the cyanide had entered Bill’s body with his usual morning dose of “salts”—a commonplace household laxative then sold under brands such as Fynnon’s. Subsequent examination indicated the poison had been added to the tin of salts kept for Bill’s morning routine, making the dose both unavoidable and plausibly administered inside the house.

In 1930s Suffolk, cyanide could be bought over the counter to destroy wasps’ nests, which complicated the inquiry.

West Suffolk police called in Scotland Yard within days. The Yard sent Detective Chief Inspector Leonard Burt with Detective Sergeant Reginald Spooner. Burt would later feature in several high-profile cases; regarding Bill Murfitt, he privately concluded he knew the culprit but lacked the admissible evidence to prosecute.

Early inquiries focused on household access and nearby acquaintances—who handled the salts, who could obtain cyanide, and who might benefit from Bill’s death. The salacious edges of village life—affairs, money worries, and rivalries—furnished motives aplenty. The press, swarming over Risby, even planted a bouquet and cryptic card in the churchyard to generate copy. Yet the evidential chain to any single suspect never came together.

The coroner’s jury returned murder; beyond that, they could not name a killer. Suspicion fell most persistently on figures with domestic proximity to the victim (especially those who could have tampered with the salts) and on a nearby gentleman farmer and landowner named James Walker and his housekeeper/companion, Fernie Chandler, who appeared frequently in statements. But without direct proof—no fingerprints in the salts, no witnessed handling of poison at the crucial time—the Crown could not proceed. The case eventually went cold.

In 2004, David Williams published Poison Farm: A Murderer Unmasked After 60 Years, drawing on village memories and a Scotland Yard report that became public in 1994. Williams argued that, assessed in the round, the balance of probability does point to a specific individual with motive, means (access to both salts and cyanide), and opportunity—effectively naming farmer James Walker as the killer the police once suspected.

In the book, Williams suggests that Bill Murfitt had grown too close to Fernie Chandler, whom Walker regarded as his partner. Bill’s death thus conveniently removed a perceived romantic and social rival. The book reconstructs local gossip and statements implying tension and jealousy in the weeks before the murder.

Further, Walker was one of the few villagers who used cyanide for pest control (common among landowners at the time). As a neighboring farmer, he could easily obtain it without suspicion. The poison in Bill Murfitt’s salts was the same type used to fumigate wasps’ nests—matching the sort of supply Walker kept.

Walker also lived within walking distance of Quays Farm, where Bill Murfitt died. He was often present or nearby, and both he and Fernie Chandler were in and out of the Murfitt household. Williams argues that either could have accessed the tin of salts in the victim’s home, but that Walker was the one who planned the act.

The book also recounts that Walker allegedly behaved oddly and evasively when questioned by police after the murder. He likewise made inconsistent statements about his movements and appeared defensive about his relationship with Chandler. Williams uncovered references in police notes to Burt and Spooner (the Scotland Yard detectives) privately believing Walker was the man responsible.

Despite the compelling theory, it should be noted that there was no forensic link—no fingerprints, eyewitnesses, or trace evidence tying Walker to the poisoned salts. Everything remained circumstantial, and cyanide was widely available. Additionally, others in Bill Murfitt’s orbit—servants, acquaintances, business partners—had opportunity and potential motives. The village was rife with jealousies, debts, and rumors, leaving plenty of reasonable doubt. And even Williams acknowledges that Fernie Chandler herself may have had both motive and access. The book implies she was at least complicit, but Walker was, in Williams’s eyes, the controlling figure and ultimate instigator.

James Walker was never charged with the murder of Bill Murfitt, and is now long dead, meaning that if he was indeed the culprit, he got away with the crime and died a free man.