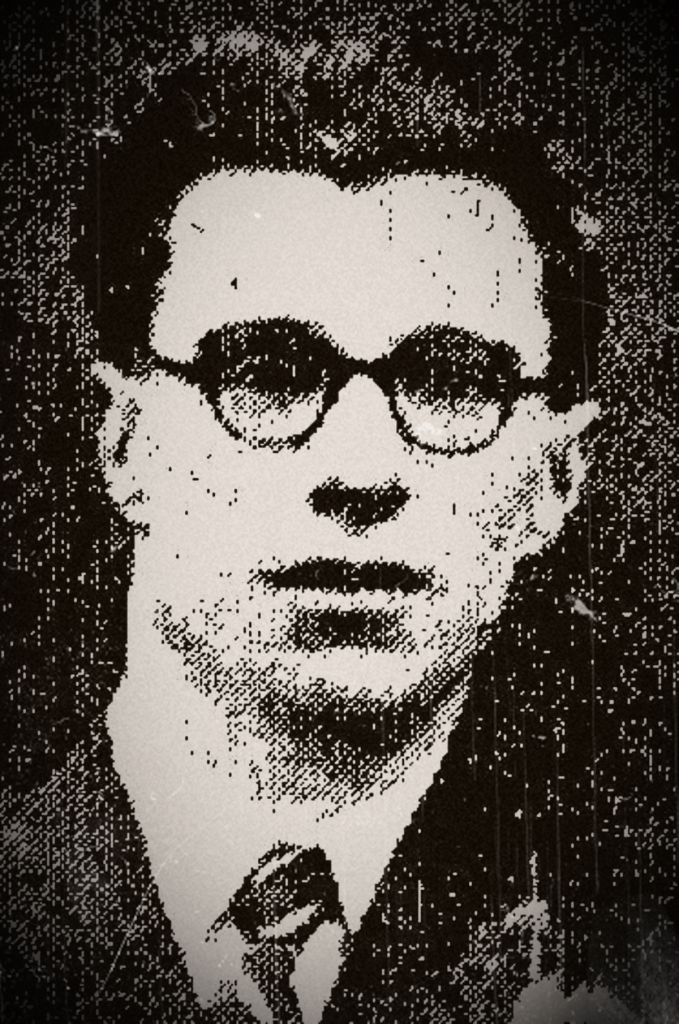

Born in 1919 in Stirlingshire, Scotland, Frederick Walter Jeffs moved to Birmingham, England as a child. He trained as an electrician at the Austin Longbridge car factory, a hub of wartime production, before enlisting in the Royal Army Service Corps during World War II. Captured as a prisoner of war, Jeffs endured the hardships of captivity, emerging with a resilience that defined his postwar life. Returning to Birmingham, he joined the Public Works Department but soon pursued his entrepreneurial dream.

In May 1953, Fred took over the confectionery and tobacconist shop at 12 Stanley Road in Quinton—a modest storefront that quickly became a local staple. With his wife by his side, the business thrived, offering candy and cigarettes to the locals.

But domestic bliss soon frayed; by September 1956, his marriage had collapsed, leaving Fred heartbroken and increasingly solitary. He devoted himself to the shop, working twelve-hour days, seven days a week, often with help from his sister or a part-time assistant. His loyal black miniature poodle, Perro, became his constant companion, a fluffy shadow trailing him through the aisles.

The separation unleashed a more adventurous side. Locals spotted Fred at the Abbey pub in Bearwood, sharing pints with women who caught his eye. Yet shadows loomed: In December 1956, burglars ransacked his home and shop, making off with £140 from the till, a watch, and a radio stashed under the floorboards. Rattled, Fred began carrying a high-powered air pistol in his raincoat pocket and kept another under his pillow—a precaution that, in hindsight, seems eerily prophetic.

April 18th, 1957 dawned like any other for the then-thirty-seven-year-old Fred. He manned the shop with his sister, dispensing Easter treats amid the holiday bustle. Around seven p.m., a young woman—described as about twenty, with dark brown hair—entered the store. Fred appeared flustered, mouthing to his sister that he’d “see her later” before ushering the visitor out. Whispers suggested a Dudley accent or even Italian heritage, but her identity remained a mystery.

By nine ten p.m., Fred locked up and drove off in his Austin A30 van, Perro presumably at his heels. But sightings painted a fragmented picture of the evening. At ten thirty p.m., the van sat unoccupied in Vicarage Road, Langley. Fifteen minutes later, a teenage neighbor glimpsed it parked behind the shop, a man at the wheel—unfamiliar and out of place. Then, around eleven ten p.m., another witness saw the same brunette woman emerge from the shop’s shadowed doorway and climb into the passenger side as the van pulled away.

Perro, meanwhile, wandered alone near Reservoir Road in Edgbaston by ten thirty p.m., his distinctive red collar later missing when he was found shivering in a nearby garage four days after the murder.

Dawn broke on April 19th with grim news: Fred’s blood-spattered van had been abandoned overnight in Brantley Road, Witton—six miles from Quinton. Crimson smears marred the hood, windshield, roof, interior, and even a headlight; vomit pooled on the seats, but there was no sign of accident damage. Fred’s empty wallet lay in the back. Police swarmed Fred’s shop, finding no forced entry but confirming a robbery: £150 vanished from the till, along with hidden floorboard cash, his watch, and radio. Stolen keys had presumably been used to enter the store.

The body surfaced hours later in a spinney dubbed “Lovers’ Lane” or the Wasson—a dark, lovers’ walkway threading Park Lane in Handsworth, between West Bromwich and Birmingham. Two boys, nine-year-old Alan Warr and his friend Ray Jones, hunting birds’ eggs during Easter break, stumbled upon the half-buried form under a hasty shroud of twigs and rocks. Fred had been savagely beaten, his head caved in by repeated strikes. Initial reports blamed a rock, but Alan Warr later revealed the true weapon: a bloodied truck starter handle, matted with hair and brain matter, which the boys found in nearby grass and hurled into undergrowth.

As they fled, a tall man in a trilby hat and long raincoat shadowed them menacingly—details that chilled detectives. By evening, with forty officers combing the scene, the handle had vanished, possibly reclaimed by the killer. A pathologist theorized the first blows struck Fred roadside near his van; dragged inside, he may have stirred, prompting the lethal frenzy—a crime of panic or passion.

Skid marks hinted at a high-speed pull-up, and a mackintosh belt knotted around Jeffs’ neck suggested he’d been hauled like discarded cargo.

Birmingham Police launched a colossal probe, knocking on doors and collecting 75,000 witness statements in a dragnet that gripped the city. Theories swirled: Was it robbery, sparked by the prior burglary and whispers of Fred’s cash hoards spreading through the underworld? A gangland hit, given the era’s shadowy crime syndicates? Or jealousy, with Fred’s pub liaisons enraging a scorned lover’s partner?

The brunette loomed largest—spotted twice that night, she vanished like smoke. Several women admitted fleeting romances with Fred Jeffs, but none fit the description. The unidentified male driver fueled accomplice talk. Detectives pegged the killers as locals, intimate enough for keys and knowledge of hiding spots, yet the trails dried up. By summer, the case went cold, and headlines faded.

In 2018, the investigation flared back to life. Graeme Rose, Fred’s great-nephew and a Birmingham playwright, delved into archives for the sixtieth anniversary, unearthing family lore and fueling a creative quest. His research led to Alan Warr—now seventy, a retired gas fitter in Tividale—who broke decades of silence in a Sunday Mercury interview. Alan recounted hurling the starter handle and the trilby-clad stalker’s gaze, details police had probed but never publicized. “It was covered in dried blood, matted hair and brains,” Alan recalled. “I remember thinking someone had killed an animal with it.”

Graeme channeled this into Fred Jeffs: The Sweetshop Murder, a play staged at Birmingham Rep, Thimblemill Library in Smethwick, and Bleakhouse Library in Oldbury—Alan Warr even made a cameo. The project expanded into a seven-part podcast, narrated by Graeme Rose, blending interviews, rumors, and reconstructions to probe Quinton’s collective memory. Echoes of gangland ties and the elusive woman persist, but no arrests followed.

The identity of the killer or killers and the motive for Fred Jeffs’ murder remain unknown as of this writing in October 2025.