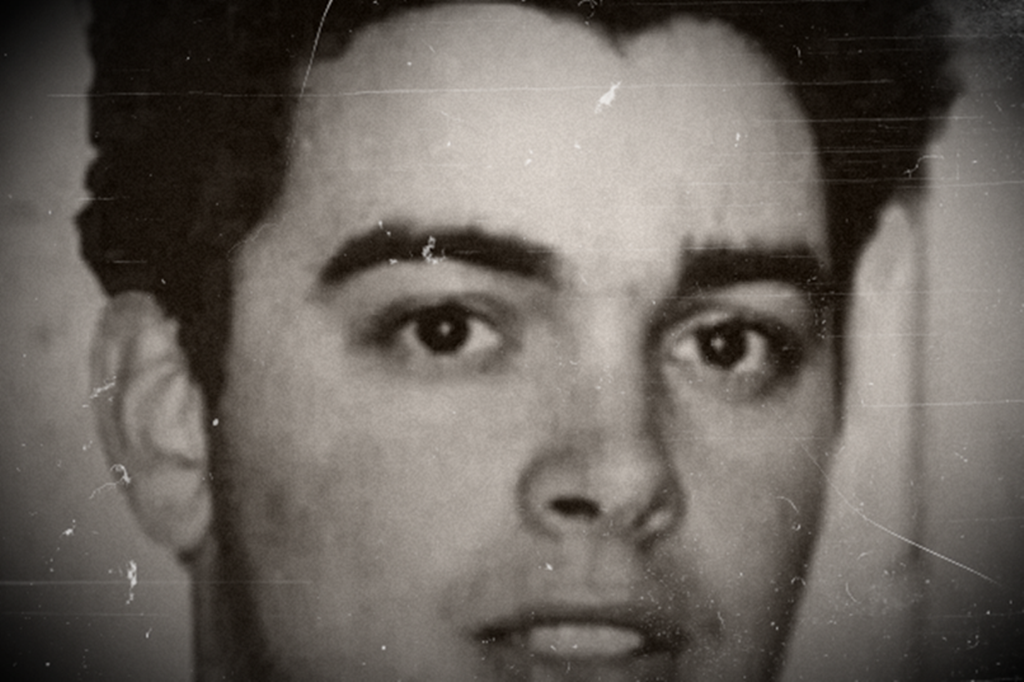

Twenty-one-year-old Andrew Gerald Elphick was born into comfortable middle-class surroundings in Surrey, England, the son of Albert Elphick, an executive at a furnishings company, and his wife. The family enjoyed the trappings of suburban success: a detached home in Normandy, near Guildford, and a new car every few years. Andrew attended St. Peter’s Roman Catholic School, where he excelled in sports but struggled academically, leaving at sixteen with six O-levels. His sights were set on the business world, inspired by his father’s career. He started as a shop assistant in Guildford, slowly climbing the ranks in menswear retail.

By his early twenties, Andrew had cultivated an image of polished sophistication. He lifted weights to stay fit, dressed impeccably, and drove a sleek Vauxhall Nova GTE. Weekends were spent at Guildford’s Braggs nightclub, where he’d linger until closing, charming crowds with his girlfriend on his arm: a woman married to a wealthier man who discreetly funded their affair. His tastes were aspirational, drawn from glossy ads: evenings with brandy, jazz records by Ella Fitzgerald, and Harry Connick Jr. on the stereo. Yet beneath the gloss lay fragility, as much of his lifestyle was borrowed, propped up by bank loans, credit cards, and pilfered perks from work.

Spring 1991 marked a turning point. Amid a biting recession, Andrew sat with his housemate and best friend, Sasha Westcourt, penning a manifesto of ambitions. In block capitals, he outlined a timeline for transformation: clear his overdraft in ninety days, snag a Porsche 911 and a helicopter in five years, and anchor a forty-foot yacht on the French Riviera. “Within nine months: new wardrobe, new car, holidays in Singapore and the South of France,” he wrote, envisioning a catered dinner party as his first reward. It was a blueprint for reinvention, but reality proved harsher.

Desperate for quick cash, Andrew and Sasha launched a string of ventures. They formed a marketing company peddling guitar-shaped ironing boards, securing a bank loan and pitching to Harrods and Argos before hawking them at Sunday markets. It flopped. Next came perfume, inspired by a glitzy conference at London’s Hilton Hotel; they recruited a sales team and blanketed streets with leaflets, but demand never materialized. Water filters followed briefly, another dead end.

Misfortune compounded. Andrew was fired from a Barnet menswear shop for dipping into the till, borrowing suits and cash, leading to prosecution and community service. He landed a job at Moss Bros in Woking, but his salary plummeted, forcing his father to bail out his debts. A car crash totaled his ride; he was obliged to finance another. Then, a CD player and credit card vanished; stolen, he claimed, though suspicions lingered.

In the months before his disappearance, Andrew fell in with a rougher crowd: two young men who bragged of wealth and criminal exploits. Over kitchen-table chats, they boasted of “disappearing” cars for insurance scams, splitting profits with Andrew as the mark. They name-dropped heavy hitters who could “bump off” rivals and floated drug deals with fat margins. Andrew, the health-conscious teetotaler who shunned drugs, was mesmerized. “Drugs. There’s a good profit margin in drugs, you know,” he once mused to Sasha. Sasha later suspected they lifted Andrew’s CD player to stage an insurance claim and coached him on fiddling £6,000 from a finance company by inflating his new Nova’s value.

Ten days before vanishing, Andrew withdrew that £6,000 in cash. Two weeks prior, he’d made a cryptic early-morning call, apologizing for missing a meeting. He dropped hints of a “big deal” but clammed up on details. His stolen credit card, meanwhile, racked up local charges such as gas and groceries, suggesting he was still in the area, or someone close was using it.

Friday, August 23rd, 1991, seemed ordinary. Andrew took the day off from Moss Bros, tanning on a sunbed at the Connaught Road house he shared with Sasha and others in Brookwood. He fielded a phone call around eight p.m., grew irritable, and bolted out a half hour later without a word, which was unusual for the sociable Andrew. He was last confirmed seen in Brookwood that evening, a familiar face in the tight-knit Surrey community.

The next morning, August 24th, locals on Slough’s rundown Northborough Estate spotted his silver Vauxhall Nova GTE, sunroof ajar, keys in the ignition, and his Filofax on the back seat. The car was unlocked, pristine: no fingerprints, hairs, or fibers, as if scrubbed clean. Slough lay eighteen miles away, an odd spot for a voluntary dump. An anonymous tipster claimed Andrew’s body floated in a nearby lake; searches and dredging turned up nothing.

Surrey Police launched a missing persons probe, but leads dried up. Door-to-doors in Slough and Brookwood were also unproductive. A BBC Crimewatch appeal drew blanks. By 1995, with no body but mounting evidence of foul play—the cash scam, the shady pals, the spotless car—detectives declared it a murder. Three men with possible links to the Connaught Road house were arrested, but released without charge. Police dug up the garden there, scouring for remains, but again found nothing.

Theories swirled: kidnapping for ransom (none demanded), suicide (no note or motive), or a deliberate vanish (unlikely, given his family ties). Sasha Westcourt, now a key informant, pointed to the criminal duo. He believed Andrew funneled the £6,000 into a drug deal they orchestrated, got stiffed, and threatened cops, sealing his fate. “They knew he wasn’t really streetwise,” Sasha said. “Andrew wanted to make a lot of money. That was his downfall… He got into something which was completely over his head.”

In 2007, forensic leaps prompted a revival. Detectives built a DNA profile from family swabs, re-interviewed witnesses, and revisited sites. They re-dug Connaught Road’s garden with archaeologists, hauling away debris. “The net is closing in,” police hinted, but no arrests followed.

For the Elphicks, closure has been elusive. Father Albert, who hired a private eye and ponied up a £15,000 reward, clings to hope: “If he was dead, then we would have found a body by now.” Detective Inspector John Cobbett disagreed; after years without a trace, survival seemed improbable.

As of 2025, Andrew Elphick’s case is still unresolved.