The 1960s was obviously an extremely turbulent decade, and during the course of the struggle for civil rights in the United States in particular, violence was a fairly common occurrence. The death of Paul Guihard, however, is notable for being the only known case of a journalist murdered during the resistance to the civil rights movement, and also merits scrutiny because his killing bore the possible hallmarks of an execution.

In June of 1962, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court found in favor of a man named James Meredith, who had applied to attend the University of Mississippi and had been denied on the basis of his race. The court’s decision sparked outrage in Mississippi, with even Governor Ross Barnett decrying the “tyranny” of the federal government “forcing” the state to allow a black man to enroll at the university, colloquially known as Ole Miss.

By the time September had rolled around, tensions were coming to a head. James Meredith was traveling to the school to enroll for classes, and a large contingent of students and prominent pro-segregationist Mississippi officials had vowed to block his entry. Ross Barnett himself had already physically obstructed Meredith’s entry into the registrar’s office on at least two prior occasions. President John F. Kennedy had sent federal marshals to the campus to ensure compliance with the court’s ruling and safeguard James Meredith’s enrollment, but it was obvious that hostilities were boiling over.

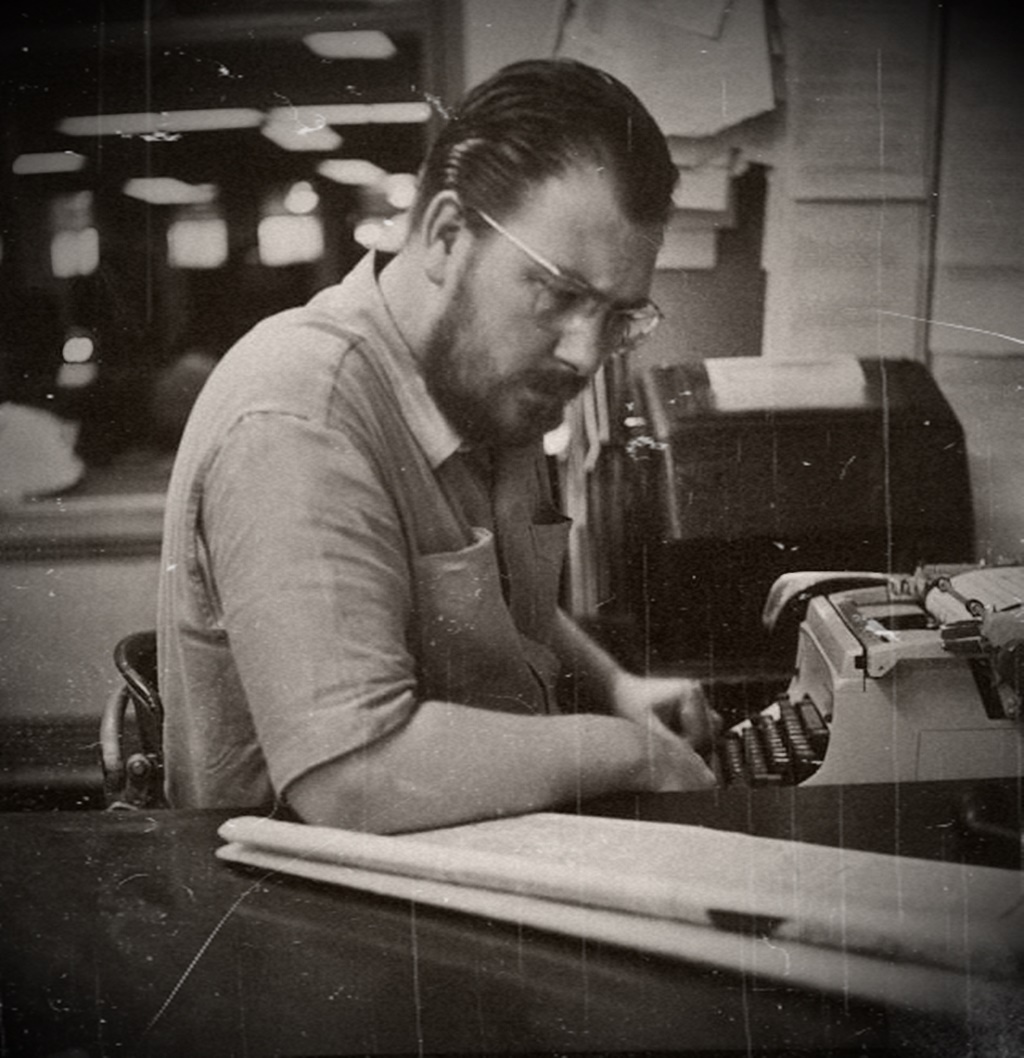

Paul Guihard entered this cauldron of rancor on the morning of September 30th, 1962. Paul was a journalist for Agence France-Press (AFP), a dual French and British citizen who had worked for the agency since the late 1940s; he was also an accomplished playwright. He was a tall, burly, red-headed fellow who answered to the nickname “Flash,” due to his dedication to the journalistic profession. By 1962, he was living in New York City and working for the New York office of AFP.

Ironically, Paul had not been regularly covering the civil rights movement, and in fact, did not usually go out on assignment at all, as his duties were mainly as an editor at this point in his career. September 30th had actually been his scheduled day off. But when the agency informed him that they were understaffed and needed someone to cover the developing story at Ole Miss, Paul didn’t hesitate to take up the challenge. Accompanied by photographer Sammy Schulman, he caught an early-morning flight to Atlanta, and then a connecting flight to Jackson, Mississippi.

Before proceeding to the campus, there is evidence that Paul and Sammy went to the governor’s office, and then to the headquarters of the pro-segregationist Citizens’ Council, where they interviewed executive director Louis Hollis. Presumably, Paul Guihard was acquiring statements from both sides of the debate to add to the story he was going to write. By all accounts, the meeting was a friendly one, and Paul filed a short piece over the phone in Hollis’ office, in which he observed that “the Civil War never came to an end.”

Paul and Sammy then drove to Oxford, Mississippi to the university campus. On the way there, they heard on the radio that the federal marshals were in place and that James Meredith had already arrived. Apparently, Paul and Sammy believed that the climax of the story had thus passed them by, but continued on anyway to cover the denouement of the action.

It was twenty minutes to nine in the evening when the two men arrived at Ole Miss, and by the time they got there, a riot had started. They agreed to part ways so that they would not be identified as journalists, but they planned to meet back up in the parking lot an hour later. Sammy Schulman circled around the campus on the outskirts of the rioting, while Paul Guihard headed straight toward the disturbance. Evidently, both men had been informed by a Mississippi Highway Patrolman that they were entering the situation at their own risk, and authorities could not promise to protect them.

Flip Schulke, a photographer for Life magazine who was also covering the story, stated that he saw Paul Guihard walking toward the rioting and warned him to turn back. According to Schulke, Paul did not seem worried, saying jokingly, “I was in Cyprus. This is nothing.” He then apparently vanished into the crowd.

At around nine p.m., a group of students walking near the Ward Dormitory heard what sounded like a man moaning. Upon investigation, they discovered Paul Guihard lying prone in a darkened area near some shrubbery east of the dormitory building. At first the students believed he had suffered a heart attack, perhaps due to the effects of tear gas, and they attempted to resuscitate him. Because of the rioting, ambulances were not able to get to the campus, but the students eventually managed to get Paul into a car and drive him to nearby Oxford Hospital.

Unfortunately, Paul Guihard was pronounced dead on arrival, and upon examination of his body, it was found that he had been killed by a single shot to the back from a .38 or .357 caliber revolver, fired from less than twelve inches away. The bullet had pierced Paul’s heart.

Though the rioting had escalated from tear gas to gunfire on both sides—and indeed, would subsequently become known as the Battle for Ole Miss, during which another man named Ray Gunter was also killed, albeit accidentally by a stray bullet—the fact that Paul Guihard had been found a significant distance away from where the riot was taking place, and the fact that he had been shot from such close range, suggested that whoever had killed him had targeted him deliberately. Investigators theorized that perhaps someone had followed him as he left the area of the rioting, or had somehow forced or lured him to a more secluded location in order to execute him. Though it is unlikely that he would have been recognized as a journalist, his physical size and distinctive red hair and goatee might have made him stand out.

If indeed Paul Guihard was the victim of an execution-style killing, what then was the motive? Mississippi State Senator John C. McLaurin, who gave a speech at a pro-segregationist rally a few days following the murder, made the unsubstantiated assertion that because Paul Guihard’s meeting with the Citizens’ Council had been civil, and because the short piece that Paul had submitted to AFP did not explicitly condemn the segregationists’ stance, that Paul Guihard himself must have been sympathetic to the segregationist cause. Therefore, McLaurin believed, Paul was likely targeted by one of the federal marshals.

However, an FBI investigation that commenced shortly after the crime occurred found no evidence that this was the case. Though it was true that the federal marshals at the scene did carry standard issue .38 and .357 caliber Smith and Wesson revolvers, these firearms were also widely available to the public, and none of the weapons confiscated from the federal marshals after the murder were found to have fired the shot that killed Paul Guihard. Ballistics tests on firearms confiscated from various members of the public after the rioting likewise did not match the murder weapon.

In the FBI report, there is a mention of two student-run segregationist groups called the Rebel Resistance and the Rebel Underground, which had been monitored by federal agents because of possible violent or criminal activity. It is unclear if either of these groups was somehow connected to the journalist’s death.

The FBI also apparently found some bullet casings in a Ford Thunderbird in an undisclosed location on campus. The report does not specify if these bullet casings were significant to the crime, who owned the car in which they were discovered, or any further specifics. Because this evidence was mentioned at all, it seems likely that investigators believed that it had something to do with the murder, but it appears that nothing further could be gleaned from these particular clues.

Whether Paul Guihard was killed because he was a journalist, because he was an outsider, because of his stance on segregation either for or against, or because he was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time has never been established. His tragic death stands as the sole known example of a journalist murdered during the Civil Rights Era. His name is inscribed, along with forty-one others, on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, which was dedicated in 1989.