It was around seven p.m. on the evening of November 30th, 1948. A couple strolling along Somerton beach near Adelaide, South Australia noticed a man in a suit sitting with his back propped against the seawall. As they watched, the man extended his arm and then dropped it limply.

About a half-hour later, another couple noticed him as well, and as they didn’t see him moving despite the clouds of mosquitoes swarming around the beach, they joked between themselves that he must be dead. Truthfully, though, they simply believed that the man was sleeping off a drinking binge, and thought no more about it.

By the time the sun rose the next morning, however, it was clear that the couple’s joke had unfortunately been grimly accurate: the man had indeed passed away. Police arrived shortly after six-thirty a.m. and began an investigation.

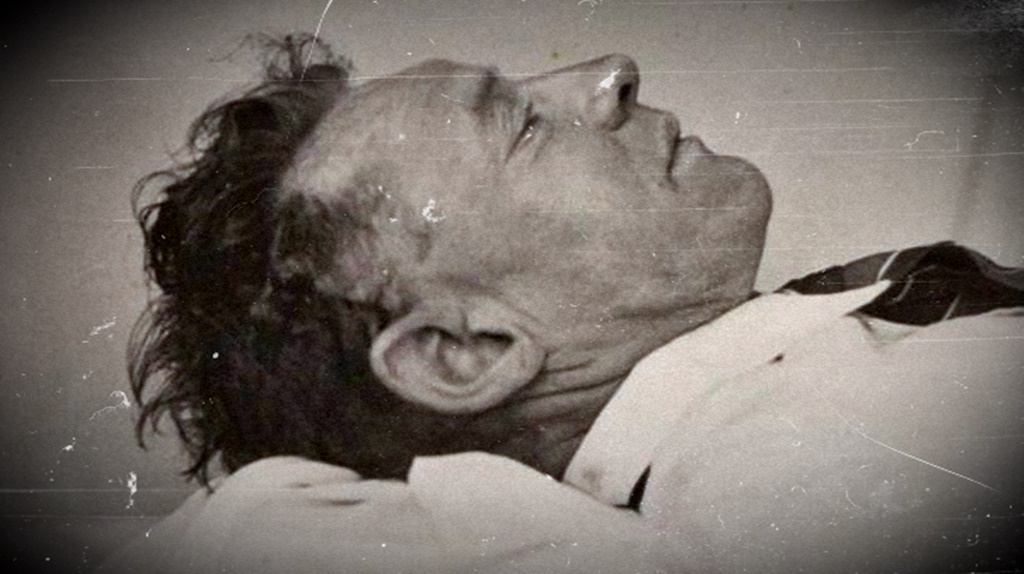

The man was thought to be between forty and forty-five years old, stood around five-foot-eleven, was well-dressed but strangely hatless, and had reddish-blond hair and hazel eyes. He had presumably died in his sleep, leaning back against the seawall with his legs extended and his ankles crossed. An unlit cigarette was found resting on his collar, as though he had been planning to light it before falling into his final sleep. His pockets contained no money or identification, but only an aluminum comb, a pack of Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit gum, a pack of cigarettes, a box of matches, an unused train ticket, and a used bus ticket.

Because there was no sign of a struggle at the site, and because the man had supposedly been seen alive the previous evening, police at first believed that the man had either committed suicide or died of some natural cause. The case began to get a little stranger, though, when the body was examined by the pathologist, John Burton Cleland.

Cleland established that the man had probably died at around two a.m. on the morning of December 1st. The report noted that the man’s body was clean-shaven and in excellent physical shape; the prominent calf muscles, narrow waist, and wedge shape of the feet and toes suggested that the man might have been a ballet dancer. Cleland stated that the man’s face had British characteristics, and that his hands were not those of a manual laborer.

The clothes of the still-unidentified man yielded a few clues as well. The labels had been removed from every piece of the man’s clothing, which was peculiar, to say the least; and his shoes were unusually clean and free of excess sand. The particular type of stitching on the jacket suggested that it might have been made in the United States. The presence of the pack of Juicy Fruit gum, additionally, pointed to the man possibly being an American, as that particular brand was not widely available in Australia at the time.

X-rays of the man’s teeth were taken, but no matches could be found. And when a full autopsy was performed, it was discovered that the man’s stomach was congested with blood, which was mixed in with the man’s final meal: a meat pie which had been consumed about three or four hours before his death. There was also congestion in the brain, kidneys, liver, and spleen, which led the pathologist to conclude that the man had probably been poisoned, though he could not determine if the alleged poison had been taken intentionally by the victim or administered by someone else.

However, no foreign substance was found in his system, and the pathologist thought it odd that the man had not vomited or appeared to convulse in the spot on the beach where the body was found; in other words, the sand around the body had been completely undisturbed. Cleland’s best guess was that the man had either voluntarily taken or been given some kind of soluble soporific or a barbiturate at some other location, and then had either traveled or been taken to Somerton beach where he was eventually discovered dead. The meat pie he had eaten shortly before his death, the pathologist believed, had not been the source of the suspected poison.

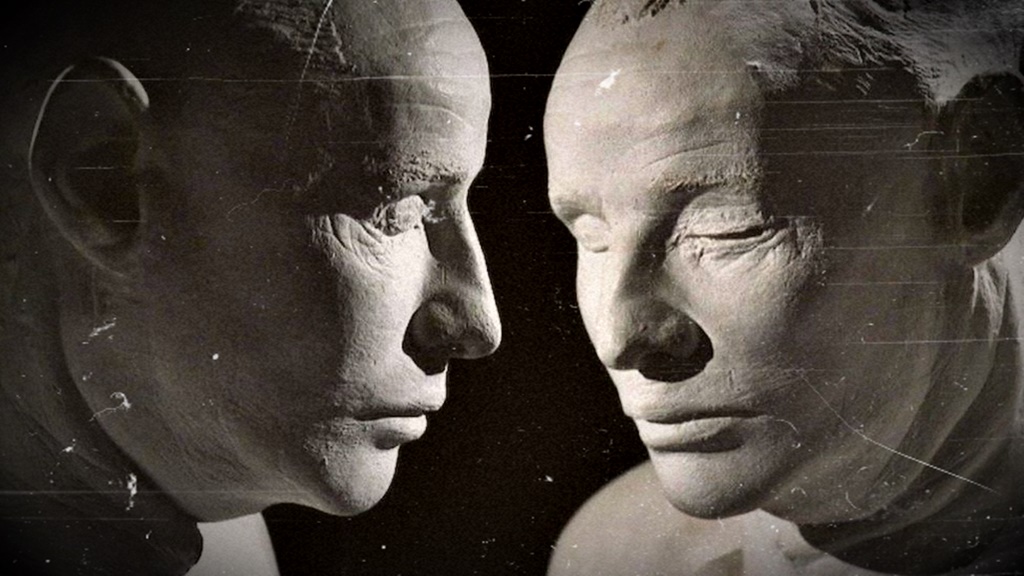

Since no one had come forward to identify the victim, who would eventually become known simply as “Somerton Man,” police had the body embalmed on December 10th, and would subsequently have a plaster cast made of the man’s head and shoulders to put on display for the public’s help in finding out who he was.

The year ended, though, with investigators being no closer to finding out the identity of Somerton Man and discovering how he had died, and as 1949 got its start, the case would begin to grow ever more bizarre. Employees at the train station in Adelaide, South Australia discovered an unclaimed suitcase in the cloakroom which had been checked sometime after eleven o’clock on the morning of November 30th, 1948, which was the day before Somerton Man’s body was found. Staff summoned the police, who made a thorough search of the suitcase’s contents.

One clue in particular pointed definitively to the case belonging to the unidentified man on the beach: a card containing an unusual waxed orange thread, made by a British company called J. Barbour & Sons Ltd, which was exactly the same thread that had been used to stitch a torn pocket lining in the trousers Somerton Man had died in. The thread was not available in Australia at the time, leading to police strengthening their suspicion that Somerton Man was an American, or at least had spent a great deal of time in the United States.

Other than the mundane items found in the suitcase, such as underwear, pajamas, and a shaving kit, investigators also discovered a few oddities that deepened the mystery of the man’s identity even further. For example, the case contained both a pair of scissors whose points had been extensively sharpened, and a regular table knife that had been turned into a shiv. There was also an electrician’s screwdriver, and a stenciling brush, of the type commonly carried by sailors on merchant ships, who used them to stencil crates of cargo.

The case also contained many other articles of clothing, almost all of which had their labels removed, just like the clothes the dead man had been found wearing. The only exceptions were a necktie which had the name “T. Keane” written on the back with a marker, a laundry bag reading “Keane,“ and a vest bearing the name “Kean,” without the “e.“ Since a search through the missing persons reports of all English-speaking countries yielded no missing person by the name of T. Keane or Kean, police were stumped as to whether this was indeed the unknown man’s name, or if it was an alias planted in the suitcase to send them down the wrong path.

Taking into account the time the suitcase had been checked in, combined with the tickets found on the man’s body, police established a possible timeline for the mysterious man‘s movements. Somerton Man, they theorized, must have arrived in Adelaide on the morning of November 30th on one of three overnight trains, coming from either Sydney, Melbourne, or Port Augusta. While at the station, he bought a ticket for the 10:50 a.m. train heading for Henley Beach, but he ended up missing this train for some unknown reason, after which he checked his suitcase at the Adelaide station and bought a bus ticket to the town of Glenelg, near Somerton beach, instead. After he arrived in Glenelg, something terrible likely befell him, but what that was, investigators still had no idea, and further progress would have to wait until the inquest, which wasn’t scheduled until several months hence, in mid-June of 1949.

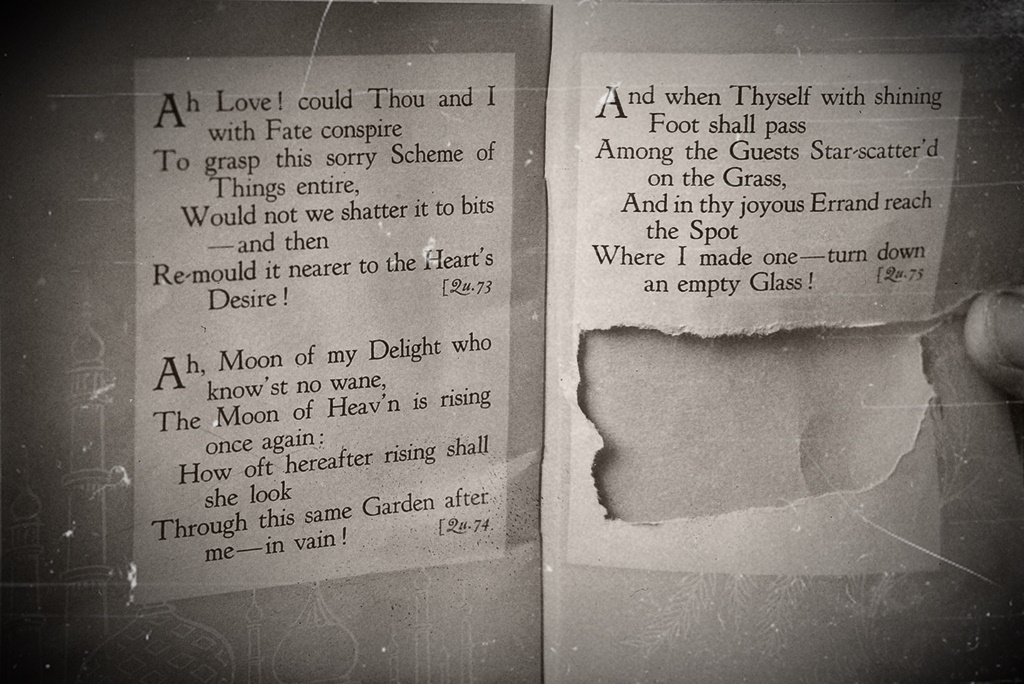

Sometime in the days before the inquest, though, investigators found something in the dead man’s clothing that they had missed the first time around: a tiny, rolled-up scrap of paper tucked into the fob pocket of his jacket. This paper appeared to have been torn off of something, and bore the words, “Tamám Shud,” a Persian phrase translating to “finished” or “ended.”

When the inquest was convened, pathologist John Burton Cleland stated that because the shoes of the Somerton Man were unusually clean and because there was little disturbance on the sand where the body was found, he believed that the victim had been given poison elsewhere and had then been left to die on the beach. Further, pharmacologist Cedric Hicks testified that Somerton Man had probably been murdered by a small oral dose of some undetectable drug, such as ouabain or digitalis, though he admitted that the lack of vomiting was strange, and was unwilling to sign off on a definite cause of death.

As the investigation continued, police began following up on the “Tamám Shud” lead, publishing photographs of the scrap of paper to get the public’s help in determining what it might mean. A few weeks after the inquest, a man pseudonymously known as Ronald Francis approached investigators and showed them a rare 1941 edition of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which had been published in New Zealand. Ronald Francis claimed that the book did not belong to him, but that he had found it in the back footwell of his car, which had been parked in Glenelg, sometime shortly before or after the day that Somerton Man’s body was found.

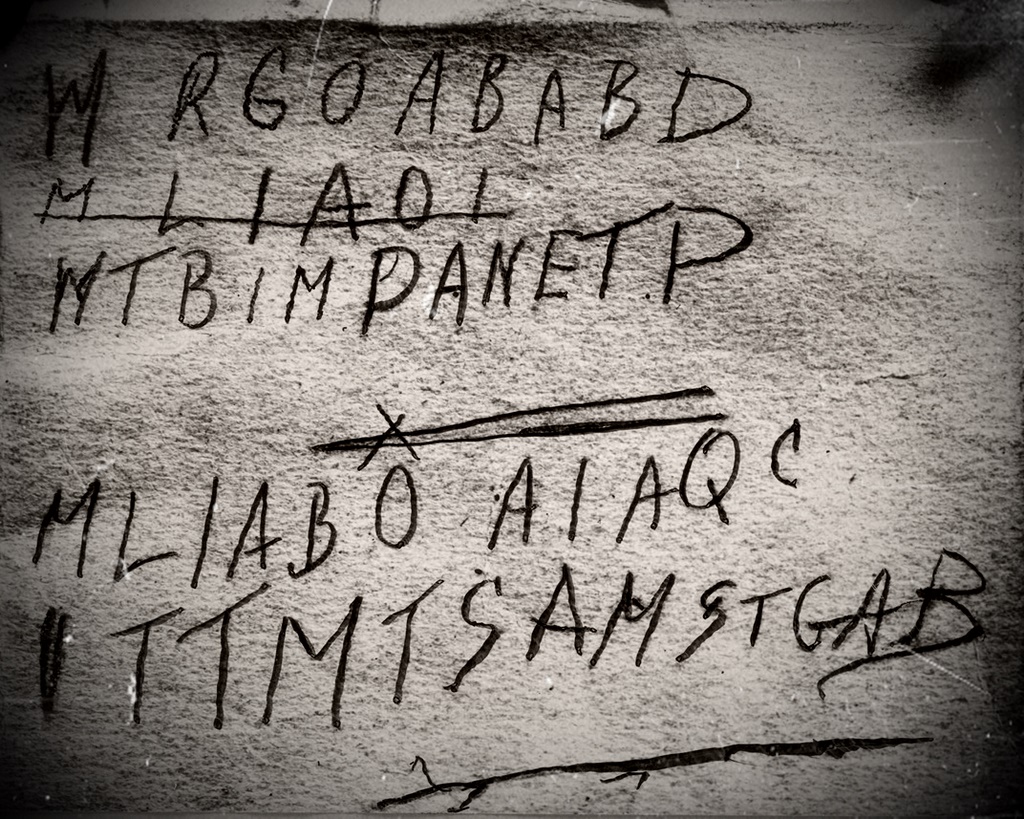

Examination of the book confirmed that the scrap of paper had indeed been torn from its final page, and the odd tome bore a few other eerie clues as well. Indentations found in the back of the book appeared to show some type of code, with five lines of random letters, one line of which had been stricken out. The code read: “WRGOABABD, MLIAOI, WTBIMPANETP, MLIABOAIAQC, ITTMTSAMSTGAB.”

Also etched into the back of the book was an unlisted telephone number, which turned out to belong to a local nurse named Jessica “Jo” Thomson, who claimed she did not know the identity of the Somerton Man when questioned by police, and further said that she had no idea why the man would have her phone number. However, Detective Sergeant Leane, one of the men working on the case, claimed that when Jo Thomson was shown the plaster cast of the dead man, she seemed “taken aback” and appeared as though she might faint.

In an even weirder twist, Jo Thomson said that she had actually owned a copy of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam when she was working at a hospital in Sydney during the Second World War. She said that in 1945, she had given the book to an army lieutenant named Alf Boxall. The coincidence seemed too perfect to ignore, so police began to suspect that the man they found on Somerton beach was Alf Boxall himself.

But a few days later, investigators got quite a shock when they discovered that their prime candidate for the unidentified victim’s identity, Alf Boxall, was very much alive. And not only that, he was able to produce the copy of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam that Jo Thomson had given him, which of course was completely intact. Inside, Jo Thomson (then known as Jessica Harkness) had written a verse from the poem before signing it with her presumed nickname, “Jestyn.”

Because of the supposed code written in the book and the labels being removed from the dead man’s clothing, the most persistent suspicions about the man had him involved in some type of espionage. It was hypothesized that Jo Thomson might have been involved as well, perhaps as some type of contact. It was also later determined that Alf Boxall rose rather quickly to the rank of lieutenant upon being transferred to a special operations unit known as the North Australia Observer Unit, leading some to speculate that all three of them were spies. There is some circumstantial evidence to support this hypothesis, but nothing concrete has ever been determined.

Interestingly, more than three years before the murder of Somerton Man, another man was found dead in a Sydney park. This man was identified as a Singaporean named Joseph Saul Haim Marshall, better known as George, and cause of death was ruled as suicide by poisoning, as a vial of barbituric acid powder was found near his left hand. Eerily enough, George Marshall’s body was found with an open copy of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam resting on his chest. The similarity between this death and that of Somerton Man does somewhat suggest an espionage-related motive for murder, though it should be noted that Marshall had attempted suicide twice before, and had spent much of his life in and out of mental health facilities.

However, advocates for a connection between Marshall’s death and that of Somerton Man point out that Marshall’s brother David later became Singapore’s chief minister, and further, George Marshall’s former girlfriend also allegedly took her own life by cutting her wrists only two months after Marshall’s death, even though she was dating another man at the time. But there is no known evidence that either of these facts are related to a conspiracy involving the death of either George Marshall himself, or to that of Somerton Man.

Authorities at this point were still frustrated by the lack of progress in identifying the mysterious victim. Almost from the moment that Somerton Man’s picture was published in the paper in late 1948, tips poured in from the public claiming to know who he was, but none of them had panned out. One of the most promising of these leads was the discovery of a World War I era military identification card issued to an eighteen-year-old British man named H.C. Reynolds. The picture on this card bore a striking resemblance to Somerton Man, even down to a mole on the cheek and the distinctive shape of the ear. However, no records of an H.C. Reynolds have been found in the archives of either the United States, the United Kingdom, or Australia, which some researchers speculate could be evidence that he was engaged in some type of classified work.

Another intriguing possibility relates back to Jo Thomson, who claimed until her death in 2007 that she did not know the identity of Somerton Man. Despite her statements, however, her daughter Kate Thomson later told the media that she suspected that her mother was a spy, and that she knew exactly who the Somerton Man was. And in fact, Jo Thomson’s son Robin, who was born in 1946, had the very same distinctive ear shape as Somerton Man, and also shared the rare genetic trait of hypodontia with the unidentified murder victim. The chances of these particular genetic traits appearing in two unrelated people are somewhere between one in ten- to twenty million, leading some to believe that Robin was actually the son of Somerton Man.

Somerton Man was laid to rest in late 1949 at the West Terrace Cemetery in Adelaide. A few years after the burial, flowers began mysteriously appearing on his grave, though police were never able to determine who was leaving them.

Interest in the case was revived in 2013, when Roma Egan, the widow of Jo Thomson’s son Robin, and Roma and Robin’s daughter Rachel, appeared on television, and petitioned the Attorney-General to have the body of the Somerton Man exhumed. Their request was denied initially, but when the next Attorney-General took office in 2019, an exhumation was approved, and finally took place in May of 2021.

In late July of 2022, a University of Adelaide team headed by Professor Derek Abbott announced that they had likely identified the Somerton Man at long last, using DNA from a handful of hairs embedded in the plaster cast of the victim that had been made in 1948. According to Abbott, the dead man was not related to Robin Thomson at all, but was in fact forty-three-year-old Carl “Charles” Webb, an electrical engineer originally from Melbourne. Born in November of 1905, Webb was the sixth child of a German man, Richard August Webb, and an Australian woman, Eliza Amelia Morris Grace.

Carl Webb married a woman named Dorothy Robertson in October of 1941, but he left her in April of 1947; she filed for divorce in 1951. No further records of Webb exist following his 1947 desertion of his spouse, and there was no record of his death, leading Abbott’s team to deduce that of the identification possibilities produced by the genetic genealogy, he was the most likely candidate for Somerton Man.

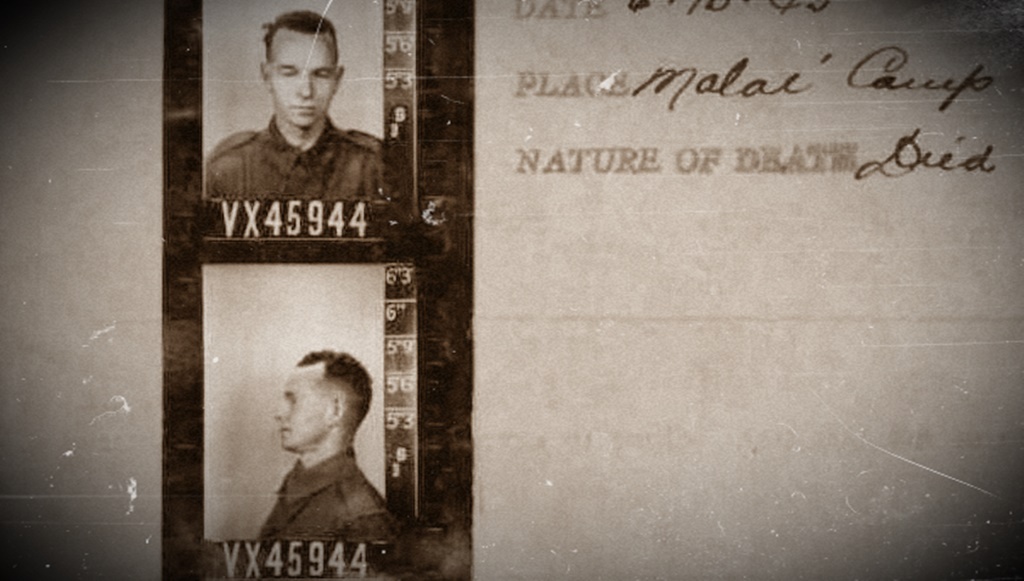

Though no photographs of Carl Webb are known to exist, researchers did unearth a picture of his brother Roy, who died in a Malaysian prisoner of war camp during World War II. Roy Webb does bear a striking resemblance to the dead man found on Somerton Beach.

Not a great deal else is known about Webb’s life, though it was discovered that one of his brothers-in-law who lived near him in Melbourne was named Thomas Keane, which would explain the “T. Keane” found written on the necktie and laundry bag in his luggage.

Furthermore, Webb was apparently quite fond of poetry and even wrote his own in his spare time, which might shed some light on his copy of The Rubaiyat, though not, admittedly, why it was found in a stranger’s car. Webb was also reportedly very interested in horse racing, and some have speculated that perhaps the strange code found inside the book had something to do with this hobby.

At this stage, in August of 2022, the South Australia Police have yet to officially verify the identification of Somerton Man. But if and when the confirmation comes, it will only (hopefully) be the first step in unraveling the still-confounding riddle of the victim’s death: why did he go to Somerton Beach that day? What was his connection, if any, to Jo Thomson? Was he murdered, or did he commit suicide? Perhaps now that his identity is known, the answers to these questions will soon be forthcoming.

On the other hand, sometimes answers to questions that seem to linger in our minds will always be elusive to us, yeah, and if this guy was somehow involved in the murky waters of espionage, military or otherwise, chances are all traces have long been erased. They’re experts at that; otherwise they wouldn’t be in business.