Dr. Mary Stults Sherman was an exceedingly accomplished individual by any definition. Originally from Illinois, she had obtained her medical degree from the University of Chicago in 1941, and subsequently served as assistant professor of orthopedic surgery at the university-affiliated Billings Hospital. In 1952, she moved to New Orleans to take up a position as director of the bone pathology laboratory at the Ochsner Clinic. In addition, she also taught at Tulane Medical School and was a well-regarded cancer researcher and orthopedic surgeon. Sadly, however, Mary Sherman would eventually become known for something far more sinister than her exemplary medical career.

At approximately four a.m. on the morning of July 21st, 1964, police fielded a phone call from a man named Juan Valdes, who lived in an apartment complex on St. Charles Avenue in New Orleans. The man claimed he smelled smoke, and firefighters were dispatched to the scene to investigate.

Upon their arrival, they saw flames emerging from apartment J, at the rear of the complex, and they burst in to extinguish the fire.

A mattress inside the apartment was merrily ablaze, and firefighters extinguished the flames before tossing it out into the courtyard. Underneath the mattress, however, they made a grisly discovery: the mutilated and partially incinerated body of a woman.

The remains belonged to fifty-one-year-old Dr. Mary Sherman. She had been viciously stabbed multiple times, in the arm, leg, stomach, liver, and heart. The murder weapon was thought to be something akin to a scalpel or an autopsy knife. The right side of her torso and her right arm had been almost entirely burned away, exposing her lungs and intestines. The walls of the apartment were splattered with blood, and though it appeared that whoever had killed her had tried to burn the evidence, there was minimal fire damage to the area around the body, a detail that would fuel numerous conspiracy theories later on.

It was clear that robbery had not been a motive, not only because of the excessive violence of the crime, but also because there were no signs of a break-in, and nothing appeared to have been stolen from the apartment. Dr. Sherman’s car was found to be missing from its usual parking space, though when investigators discovered it later that afternoon about nine blocks away, it yielded few clues, other than an empty cartridge from a tear gas container. The car keys were discovered in a hedge a further three blocks away, but no evidence was gleaned from them either.

It appeared that authorities investigated several different possibilities with regards to the doctor’s brutal slaying. The first of these was that Mary Sherman was the victim of a crime of passion, perpetrated by a spurned lover. Though police reports at the time demonstrate that there were various rumors circulating around town that the doctor had been murdered by a woman she had once been romantically involved with, there appeared little solid evidence to support any of these vague claims.

Additional prospects were drawn from the pool of Dr. Sherman’s colleagues, coworkers, and patients. Clinic director John Oschner attracted suspicion when he allegedly walked into Dr. Sherman’s lab on the day following her murder and told the assembled residents, “You’d better have a good alibi.” Oschner later claimed he had simply been making a tasteless joke.

Much weirder was an anonymous call received by the Metropolitan Crime Commission. The female caller allegedly made reference to Dr. Sherman’s murder being the second mysterious death among her “friends here at Oschner,” and further linked Dr. Sherman’s murder with a Mafia-related narcotics operation that involved people entering the Oschner Clinic in full-body casts in which they were smuggling drugs.

Another strange phone call was reported by another doctor at the clinic and also Mary Sherman’s best friend, Carolyn Talley, who stated that the man on the other end of the line had told her, “Dr. Talley will be next.”

Several other doctors on staff recommended to police that they look into a man named Stanley Stumpf, a resident who had worked under Dr. Sherman the previous year. In their statements, these other doctors asserted that Stumpf had come into the clinic on the night of the murder, even though he was not scheduled to work that evening, and was acting in a manner that seemed to be engineered to draw attention to himself, almost as though he was trying to establish an alibi. Investigators apparently never interviewed him, though a few years later, a woman who had been dating him claimed that she had to take out a restraining order because he was a drug addict who behaved erratically. She also made note of the chilling fact that he was known to carry a container of tear gas in his car, as well as an axe and a chain saw in his trunk at all times.

Dr. Sherman’s neighbor, Juan Valdes, the man who had initially called in the fire, thus alerting police to the murder, was also considered a suspect, mainly because various neighbors and acquaintances had accused him of making “obscene advances.” Indeed, one couple had even filed a restraining order against him. It was also thought suspicious that even though he had claimed not to know Dr. Sherman very well when he was questioned shortly after the murder, he later evidently told numerous people that he and Dr. Sherman had actually been rather close.

However, by far the strangest theories surrounding Dr. Sherman’s murder stemmed from the seemingly unusual fact that although the right side of her body had been all but burned away, the area surrounding her—including the carpet and nearby curtains—was not damaged by the flames at all.

Several pathologists who looked into the case did not find this detail particularly notable, insisting that the reason only part of the body burned could have been because those particular areas had been soaked with accelerant. They also theorized that the fire hadn’t spread to any great degree because of the mattress thrown over the remains.

But writers Ed Haslam and Joan Mellen believed that the reason for the purported oddity of the injuries had to do with the fact that Dr. Sherman was not actually murdered in her apartment, but died elsewhere and was later placed there to make it look as though it had been a random killing. They even speculated that the burns had been the true cause of death, and that the stabbing had been done post-mortem, to cover up some nefarious project that Dr. Sherman had been involved in.

This project was said to be a covert CIA operation that was developing a top-secret vaccine and/or a biological weapon that was evidently going to be used to assassinate Fidel Castro. Dr. Sherman and the founder of the Oschner Clinic, Dr. Alton Oschner, were allegedly involved in this clandestine research. Someone else who had apparently been hired as a cover for this operation was none other than Lee Harvey Oswald, the man who assassinated President John F. Kennedy in 1963.

Haslam and Mellen also found it suspicious that the day Dr. Sherman was murdered was the same day that the Warren Commission was set to hear testimony about Lee Harvey Oswald’s movements and activities in Louisiana. Haslam has further speculated that the reason the FBI will not release Dr. Sherman’s address book is because it contains Oswald’s name.

The story went that Dr. Sherman was accidentally burned to death by the linear particle accelerator she had been working with at the Infectious Disease Laboratory in New Orleans. But because the work she was involved in was top secret, higher-ups ordered her body moved to her apartment, stabbed, and then set on fire so that it would look as though she had been the victim of a tragic crime.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the suspect list in the bizarre slaying of Dr. Mary Sherman remains rife with intriguing possibilities, but the murder itself is still unsolved, nearly six decades later.

Almost three months after Dr. Sherman’s mysterious death in New Orleans, a woman who was definitely connected with both President John F. Kennedy and the CIA would turn up murdered in Washington DC.

Mary Pinchot Meyer was originally from New York City, hailing from a wealthy and influential family that was quite active in progressive politics. She graduated from Vassar in 1942, and thereafter worked as a journalist for many years, in addition to being an abstract artist who made no secret of her involvement in the counterculture, even to the extent of openly hanging out with Timothy Leary.

She married Marine Corps lieutenant Cord Meyer in 1945, and after he began working for the CIA around 1951, the couple moved to Washington DC and became involved with the upper echelons of Georgetown society, keeping company with politicians, journalists, and members of the intelligence community.

The Meyers’ high-class lifestyle was anything but perfect, however. Mary, a pacifist and a hippie artist type, had always been looked at with slight suspicion by her husband’s colleagues. Cord Meyer, also a pacifist despite his profession, likewise became disillusioned with the intelligence community after the infamous Senator Joseph McCarthy accused him of being a Communist, and it was confirmed that the FBI had been watching him and his wife. His superiors at the CIA vouched for him and he kept his job with the agency, though his heart was no longer in it.

Even more tragically, the week before Christmas of 1956, one of the couple’s three sons, nine-year-old Michael, was struck by a car outside their home and killed. The subsequent emotional turmoil caused by the child’s death eventually led to the Meyers divorcing in 1958.

After the divorce, Mary took up painting in earnest, maintaining a small studio in the garage of her sister and brother-in-law’s Georgetown home. Mary also, most notoriously, began an affair with President John F. Kennedy. According to several sources, she would often visit the White House while Jackie Kennedy was away, spending a great deal of time with the president, during which they not only engaged in intimate activities, but also allegedly indulged in marijuana, LSD, and cocaine. In fact, only a month before his assassination, Kennedy wrote a letter to Mary Meyer asking her to come see him, though it seems that she never received it.

Whether Mary’s involvement with the president had any connection to her death is still a matter of much speculation, and there are compelling arguments on either side. But whatever the motive might have been, Mary Pinchot Meyer would only outlive Kennedy by less than a year.

It was October 12th, 1964. Mary had spent the morning painting in her studio, and at around lunchtime, she set out for her customary walk along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal towpath. Along the way, she spotted her friend Polly Wisner passing by in a car, and they spoke briefly. Polly and her husband were apparently the last people other than her killer to see Mary Meyer alive.

At around twelve-twenty-five p.m., two mechanics on the opposite side of the canal who were preparing to tow a stalled car reported that they heard two gunshots and a woman’s voice screaming, “Someone help me!” One of the mechanics, Henry Wiggins, told police that he had looked across the canal upon hearing the sounds and saw a black man wearing a dark cap standing over a prone white woman.

When police arrived at the scene, they found the body of Mary Pinchot Meyer. She had been shot twice at point-blank range; once in the back and once in the temple.

It didn’t take long before authorities snagged their first—and to this date only—suspect: Ray Crump. He was seen walking through the park about a quarter of a mile from the murder site, and he was soaking wet. When police questioned him, he gave conflicting answers as to what he’d been doing at the park: first he said he had dropped his fishing pole into the canal and jumped in to get it, then he said he’d been drinking and simply fallen in.

Henry Wiggins identified Crump as the man he had seen standing over Mary Meyer, and another witness, Lt. William Mitchell, also testified that he had been jogging in the park the previous day and had seen a man matching Crump’s description following Mary Meyer along the path.

It seemed an open and shut case, but bothersome little details kept cropping up. The murder weapon was never found, and no blood was present on Crump’s clothing, even though the coroner’s report stated that the head wound would have bled profusely. Conversely, a journalist named Lance Morrow, who arrived at the scene about ten minutes before police, stated that the gunshot wounds appeared strangely bloodless.

Additionally, there was some question over whether Henry Wiggins could have clearly identified Ray Crump from his position across the canal. And even stranger, when the garage where Wiggins worked was asked to provide records of the car that was being towed on the day Mary Meyer was murdered, no such records were found to exist.

Some later sources even claimed that Lt. William Mitchell, the man who stated he had seen Crump following Mary Meyer the day before she was killed, was actually a CIA operative who had been tasked with keeping tabs on Mary Meyer, and was eventually commanded to “take her out,” presumably because of her reaction to the recently-released Warren Commission report into the assassination of President Kennedy. Similarly, Mary Meyer’s diary was allegedly handed over to the CIA and destroyed.

Ray Crump did stand trial for the murder, but was eventually acquitted. No forensic evidence whatsoever connected him with the crime, and it was asserted that the mechanics’ witness testimony about the man they had seen standing over the body described a man much taller and heavier than Crump. Though Ray Crump would subsequently go on to commit other crimes, few modern researchers believe he was guilty of Mary Pinchot Meyer’s murder.

But if Crump wasn’t the killer, then who was? Some have speculated that another, un-apprehended black man was in the park that day, and randomly targeted Mary Meyer for robbery or rape, but ended up shooting her dead when she fought back. Still others assert that Mary was the victim of a covert assassination, and was murdered because she knew too much about President Kennedy and CIA operations.

Writers arguing against the conspiracy hypothesis point out that had the CIA wanted Mary Meyer dead, they certainly could have engineered her assassination in a much more measured and private manner, such as in her home, rather than having her killed in a public park in the middle of the day, when there were so many factors and witnesses in the environment that they would not be able to control.

Mary’s ex-husband Cord Meyer, who worked for the CIA until 1977, did not believe that the agency had targeted his ex-wife, but that she was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time and fell victim to a random attack by a potential mugger or rapist.

The debate continues to rage, with the case spawning numerous books and even inspiring a 2009 film titled An American Affair.

A gruesome crime that occurred less than a year later in Texas had even more obscure motives, and though the guilty party has almost certainly been identified, actually tracking him down has proved to be a far more difficult task. Like the murders of Dr. Mary Stults Sherman and Mary Pinchot Meyer, discussed above, this particular crime has also been rumored to have links to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, though the connection seems somewhat tenuous.

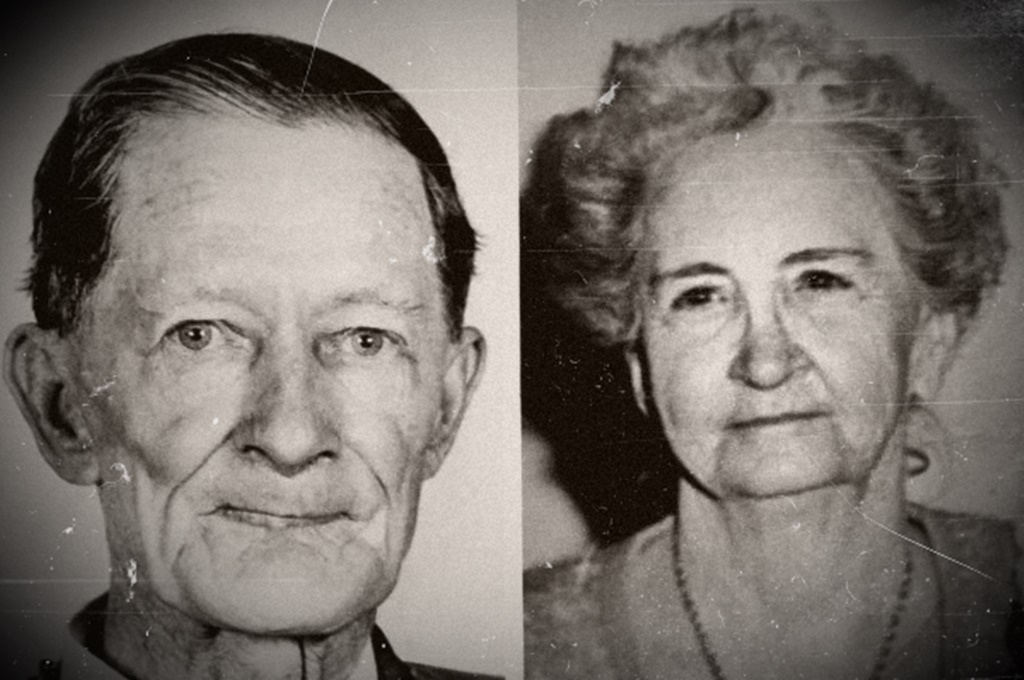

Fred and Edwina Rogers were an elderly couple who lived in a home in the Montrose neighborhood of Houston. In the early summer of 1965, their nephew Marvin became concerned when neither his aunt nor his uncle had answered his phone calls for several days. Marvin called the police to have his relatives checked in on.

Authorities entered the home on June 23rd, and at first saw nothing amiss, save for some food that had been left out on the dining room table. A more thorough search of the ground floor was equally unforthcoming, though one officer, C.M. Bullock, found it curious that there was a great number of washed and unwrapped cuts of meat stacked in the refrigerator. But this was Texas, after all, and the meat appeared to be from a butchered hog, so police were about to close the fridge door and resume their investigation.

It was then, however, that Bullock spotted a pair of severed heads staring at him from the bottom crisper drawer.

The heads, of course, belonged to Fred and Edwina Rogers, as did the butchered cuts of flesh neatly arranged on the upper shelves. Edwina had been shot in the head at close range. Fred had been beaten to death with a claw hammer and then had his eyes gouged out. Both victims had their organs and genitalia removed. Some of these organs were later found in a nearby sewer line, as presumably the killer had cut them up and flushed them down the toilet in pieces. Some body parts were never found.

It didn’t take very long for the most likely culprit for the horrific slaying to come to light. Though the house had been stringently cleaned, including the bathtub where the bodies were probably dismembered, there were some traces of blood evidence, as well as a blood-stained keyhole saw, found in the bedroom of the Rogers’ forty-three-year-old son Charles.

Charles Frederick Rogers was a rather enigmatic individual. He was a former Navy pilot who had served in World War II, had earned a degree in nuclear physics, and worked as a seismologist for Shell Oil for nine years. He was described as extremely intelligent, was conscientious and good at his job, and spoke seven languages. After later joining the Civil Air Patrol, he was alleged to have become acquainted with David Ferrie, who would later be named as a conspirator in the JFK assassination.

Charles Rogers quit his job with no explanation in 1957 and by all accounts became something of a hermit. He moved into the house on Driscoll Street in Montrose with his parents Fred and Edwina, and reportedly only communicated with them by writing notes and pushing them out from beneath the door of his attic bedroom. Although he was unemployed, he often left the house before dawn and only returned after dark, so that most neighbors had no idea that he had been living there at all.

It seemed crystal clear to investigators that Charles Rogers had brutally murdered his parents for reasons known only to him; the only problem police faced was in finding where the prime suspect in the so-called “Houston Ice Box Murders” had gone. A nationwide manhunt commenced.

Needless to say, because the crime is still categorized as unsolved, the search for Charles Frederick Rogers was ultimately unsuccessful. Though there were alleged sightings of him in locations as varied as Canada, East Texas, and Honduras, no trace of the man was ever uncovered, and at last, ten years after his vanishing act, a judge declared him dead in absentia so that his estate could be probated.

Because of Rogers’ purported association with David Ferrie, some later researchers have speculated that Rogers may have been a CIA assassin who sometimes impersonated Lee Harvey Oswald, and was in fact one of the men on the infamous grassy knoll on the day John F. Kennedy was killed. This hypothesis, put forward in a 1992 book called The Man on the Grassy Knoll by John R. Craig and Philip A. Rogers, puts forth the idea that not only was Charles Rogers one of Kennedy’s assassins, but also that he had murdered his parents because they had been listening in on his phone calls and had discovered his involvement in the conspiracy.

Other researchers dismiss this claim as unfounded, and speculate that Charles Rogers killed his parents because they were abusive criminals who had stolen large amounts of money from Charles until he had finally had enough. In this scenario, put forward by Hugh and Martha Gardenier, Charles fled to Mexico after the murder and was protected by powerful individuals he knew from his days at Shell Oil, though he was later supposedly killed in Honduras during an unrelated dispute.

The case remains officially unresolved, and has been the subject of several books, including two fictional mysteries by James Ellroy.